INTRODUCTION

Upper eyelid cicatricial entropion (UCE) is a common cause of trichiasis and results from any pathological process that causes scarring of the tarsal plate and consequent inward rotation of the lid margin. In several regions of the Middle East and Africa, trachoma is the most common cause of UCE(1). In Western countries, UCE is usually due to a variety of other causes including chronic blepharitis, previous surgeries, pemphigus, chronic use of topical glaucoma medications, and anophthalmic socket contraction(2).

As trachoma is an ancient blinding disease, there is a considerable amount of literature on surgical techniques for correcting trachomatous UCE that can be traced back to ancient Chinese medical texts(3). Most modern procedures are based on a horizontal tarsotomy across the entire tarsal plate and the use of sutures to evert the lid margin. In English literature, a majority of authors advocate different variants of the anterior approach described by Wies during the 1950s for spastic entropion of the lower eyelid(4,5) as well as that used by Ballen(6) to rotate the upper lid margin in cases of cicatricial entropion. These surgeries were typically performed with a through-and-through incision placed 3 mm or 4 mm from the lid margin(7-11). In African French-speaking countries and many places in the Middle East, the posterior approach as described by Trabut is the preferred procedure(12).

We describe a lid crease approach with internal absorbable sutures for upper lid margin rotation in cases of trachomatous cicatricial entropion. This is a versatile procedure that does not require any bolsters and allows the surgeon to correct the lid margin position and simultaneously address a variety of associated conditions with a single external incision.

METHODS

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for a chart review of patients with trachomatous cicatricial entropion who underwent surgery at the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). All surgeries were performed with an anterior approach and a lid crease incision. Preoperatively, all lids had trachomatous entropion, trichiasis, and the typical conjunctivalization of the margin with the mucocutaneous junction overriding the meibomian gland line. Other signs of trachoma, such as Herbert's pits and corneal pannus, were also present in all cases.

Postoperatively, the position of the lid margins was assessed with slit-lamp biomicroscopy in all patients. The degree of rotation was categorized as good only when the meibomian gland orifices were clearly visible without any traction on the anterior lamella and were not covered by the tarsal conjunctiva. Any residual trichiasis or inward displacement of the meibomian gland line was registered as unsatisfactory.

Surgical technique

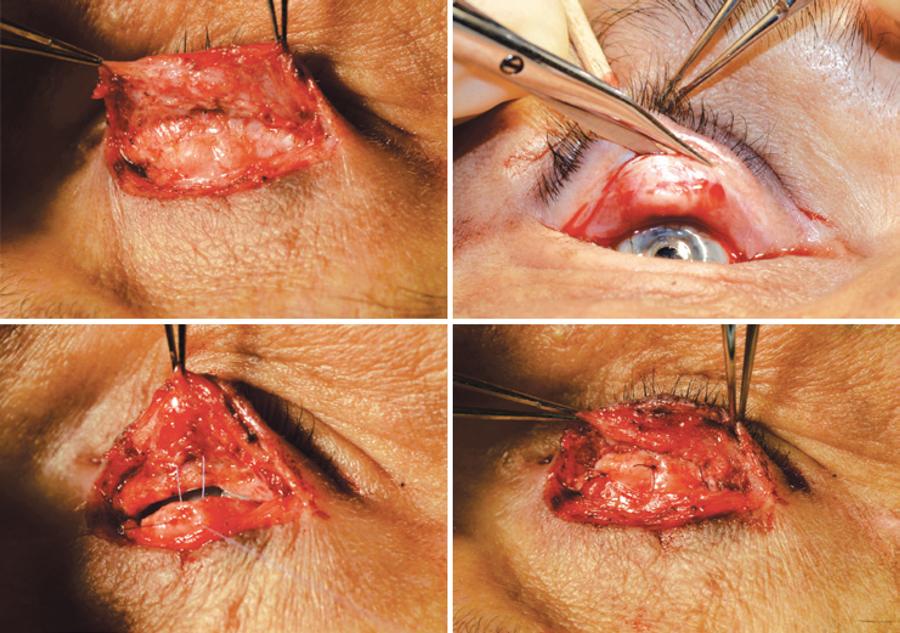

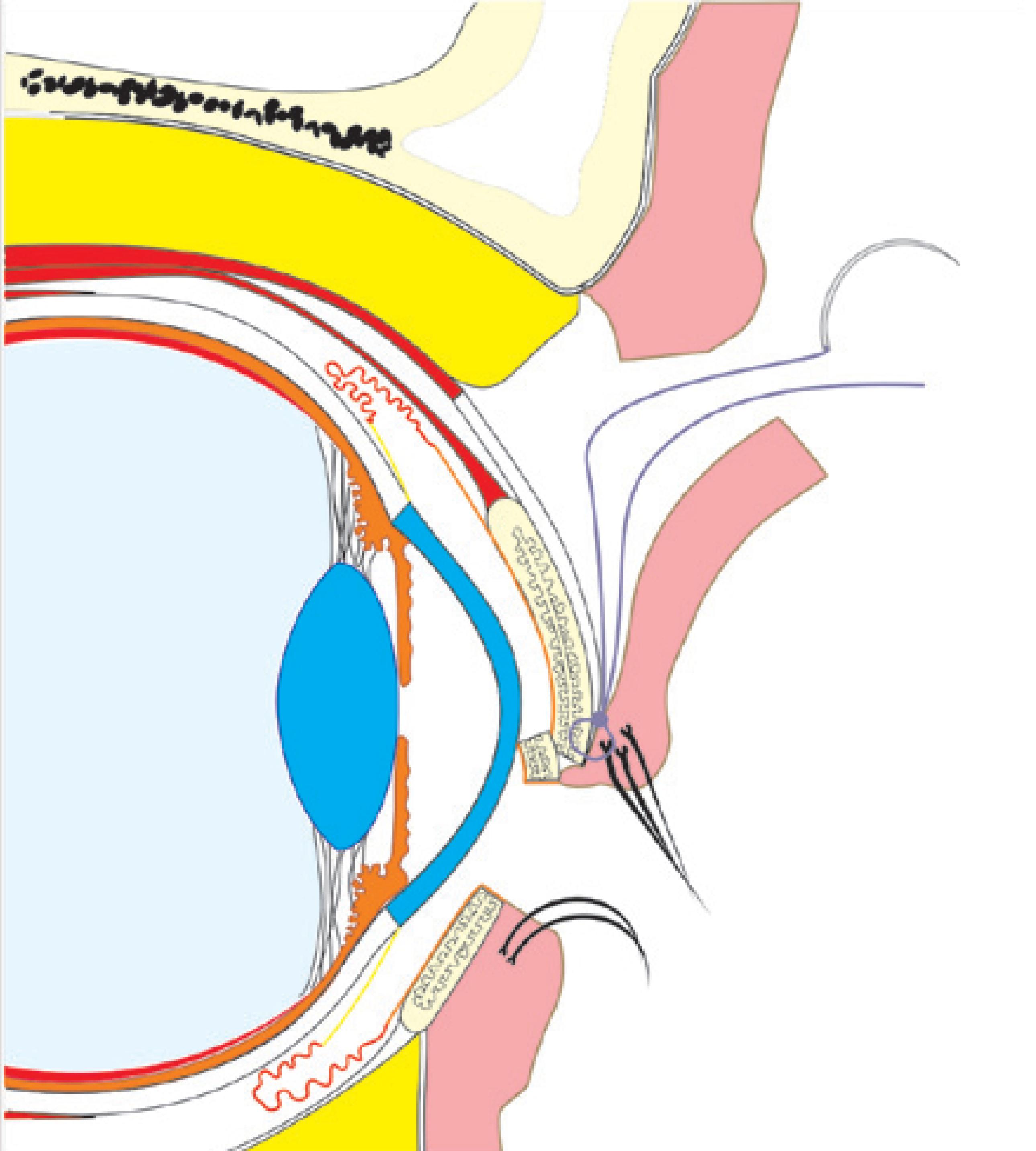

The surgery (Figure 1) is performed with local anesthetic (2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine). Initially, a 4-0 silk traction suture is inserted through the tarsal edge of the lid margin. Next, a standard lid crease incision is used to create a pretarsal skin-muscle flap. At this point, if desired, a standard blepharoplasty skin/muscle resection can be performed. The pretarsal skin-muscle flap is raised, exposing the whole tarsal plate and dissection under the pretarsal orbicularis muscle with Westcott scissors or a Colorado needle proceeds towards the lid margin until the lash roots are visible. The eyelid is everted over a cotton-tipped applicator and held in position with the traction suture. During this maneuver, care is taken to place the applicator under and not over the skin-muscle flap. Using a No. 15 Bard-Parker scalpel blade and Westcott scissors, a curved incision paralleling the lid margin is made through the full thickness of the tarsus 3 mm posteriorly to the margin. Next, the lid is returned to its natural position. Three double-armed 6-0 polyglactin sutures are then passed through the central, medial, and lateral aspects of the distal cut edge of the tarsus and attached to the orbicularis muscle near the lash line. As the sutures are tied, the distal portion of the tarsus is advanced over the marginal tarsus, and the marginal orbicularis is pushed backward, rotating both lamellae of the lid margin outward (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Top: Left - a standard lid crease incision is used to raise a pretarsal skin-muscle flap, exposing the whole tarsal flap until the lash roots are visible. Right - tarsotomy is performed with a conjunctival incision 3-4 mm from the lid margin. Bottom: left - a 6-0 Vicryl suture is passed on the orbicularis muscle close to the lash roots and through the mid portion of the distal tarsal fragment. Right - as the sutures are tied, the distal tarsal fragment is slightly advanced over the marginal tarsus and traction is exerted on the orbicularis.

Figure 2 Double mechanism of lid rotation. The distal fragment exerts a downward vector on the marginal tarsus, and the internal suture tractions the anterior lamella near the lash line.

Using this method, the sutures remain within the lid, and no bolsters are used. The lid crease incision is closed with a running 6.0 fast absorbable suture.

RESULTS

Sixty upper lids of 40 patients (23 women and 17 men) were operated on, with an age range of 44-99 years [mean ± standard deviation (SD) = 70.9 ± 13.01 years]. Bilateral surgery was performed on 21 patients. Follow-up ranged from 1 to 12 months (mean 3.0 ± 2.71 months). Forty percent of the patients (24 lids) had more than 3 months of follow-up, and in this subgroup, the mean postoperative time to final follow-up was 5.6 ± 2.68 months. Trichiasis was corrected in all but one lid, which had two inward lashes medially touching the cornea despite adequate margin position, and was managed with lash electrolysis. Figure 3 shows a typical effect of the surgery on patients with cicatricial entropion and residual vision in the right eye.

DISCUSSION

UCE is usually seen in aged patients, who may also present with other lid problems, such as dermatochalasis, aponeurotic ptosis, upper sulcus deformity, anterior lamella laxity, and lid retraction. In endemic trachomatous areas, the clinical picture can be quite obvious, with severe trichiasis and blepharospasm. In mild cases, the condition may be difficult to diagnose and is commonly called “rubbing lashes”(2). A typical sign is an abnormal location of the mucocutaneous junction that overlies the meibomian gland line (13-15).

The current literature on the surgical correction of UCE is heavily based on epidemiological studies reporting the outcomes of a large series of procedures that are usually not performed by ophthalmologists from rural communities with few medical resources(16-18). In this context, the ideal procedure is the simplest operation that can be successfully performed in the least amount of time. In African French-speaking countries, the preferred procedure is Trabut surgery, which is a posterior tarsotomy with external sutures secured by bolsters(12). From a mechanical point of view, in this surgery, lid rotation is achieved by the advancement of the distal tarsal portion over the marginal tarsus. The tarsal overlap creates a downward vector on the posterior edge of the marginal tarsus and rotates the lid margin upward.

The World Health Organization recommends the same anterior approach procedure described by Ballen in 1964(6,10). The mechanics involved in the margin rotation in the Ballen procedure is based on a tarsotomy, without any tarsal overlap, and traction on the anterior lamella with external sutures.

We believe that in more conventional surgical settings, an anterior incision placed 3 mm from the margin is not the best approach to address upper lid entropion. There are several advantages with the use of a lid crease incision. Firstly, the tarsal plate and the anterior lamellae are not incised on the same level. This reduces the chances of ischemia of the narrow marginal lid strip that is created with a classic Ballen surgery. Secondly, the suborbicularis dissection can be easily performed until Riolan's muscle is reached. Absorbable sutures can then be passed internally on the marginal portion of the orbicularis muscle, thus increasing the upward rotation of the lashes without the use of bolsters or subsequent suture removal. The absence of bolsters or external sutures renders a more comfortable postoperative care. Thirdly, the tarsal plate is not incised. The distal portion of the tarsus is slightly advanced over the marginal portion, thereby creating the same mechanical downward tension on the margin as described by Trabut(12).

Theoretically, this effect keeps the lid margin rotated, thus decreasing the chances of entropion recurrence. Although the advancement of the distal tarsus fragment over the marginal portion slightly shortens the posterior lamella, we did not observe any retraction, and if needed, the surgeon can address any positional anomalies of the lid recessing or advancing the levator aponeurosis at the end of the margin rotation.

An important limitation of our study is the short postoperative follow-up time. It is well known that the rate of trichiasis recurrence is quite high when non-oculoplastic surgeons perform community-based lid margin rotations(15,19). For example, trichiasis occurs in 20% to 40% of cases after a bilamellar tarsal rotation procedure (Wies/Ballen operation) or a posterior lamellar tarsal rotation (Trabut surgery)(15,19). The recurrence of trichiasis appears to be multifactorial in nature; however, tarsotomies that are non-parallel to the eyelid margin are associated with poor margin rotation (20). The lid crease approach combines the advantage of complete tarsal exposure with the ability to perform the tarsotomy through the conjunctiva; thus, the surgeon is able to simultaneously visualize both the lid margin and tarsal incision at all times, allowing careful control of the location of the tarsotomy.

A discussion on the long-term effects of our margin rotation procedure is not possible at this time. However, we believe that the procedure is stable and can also be used to correct other forms of cicatricial entropion, such as those induced by tarsal buckling after supramaximal levator resection. The authors have used the described lid crease approach to correct UCE in patients at the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital. The level of satisfaction is quite high, and we did not observe any serious complications, such as lid margin necrosis or deficient fissure closure. In addition to the functional outcomes, the cosmetic aspect of this procedure is superior to that of other techniques.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin