Harley E. A. Bicas

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2025-0242

ABSTRACT

In Part II, this paper addresses ocular motions, their causes (forces), and the governing laws, beginning with the fundamental question: Why do the eyes move? Ocular rotations and different types of translations (ocular, orbital, and corporeal) are reviewed. The discussion then turns to how the eyes move, where concepts such as the plane of muscular action, torque, and arc of contact provide possible explanations for the anatomical arrangement of the ocular muscles within the orbit. Sherrington’s law of reciprocal innervation is used to explain the distribution of muscular active forces in a conservative mechanical system, but in combination with Hering’s law, it may prevent eye rotation (e.g., isometric contractions of antagonist muscles of an asymmetrical convergence). Normally, however, the limitation of an eye rotation is determined by passive forces, evoked by muscular activity itself, particularly natural muscular elasticity. Thus, elongation of an antagonist muscle may passively restrict the active contraction of an agonist. In addition to mechanisms for initiating rotation (active forces) and stopping it (passive forces), the oculomotor system also requires a means of dissipating energy (dissipative forces) to initiate subsequent movements. Hence, it cannot function as a perfectly conservative system of forces. The paper concludes with a review of “selective” effects of muscle function (due to the sparse distribution of fibers), the role of intermuscular membranes (and pulleys), and mechanical considerations of surgical procedures, such as muscular transpositions to alter or abolish actions (e.g., bifid reinsertions). Part III will address the diagnostic complexities of the oculomotor system, general treatment principles, and ocular fixation (eye and head positions). Although the basic concept of the primary position is relativized, the absolute need for referential conditions in defining, qualifying, and measuring strabismus is emphasized. The prim-diopter is challenged due to its lack of “linearity” relative to angular units, and an alternative is proposed. Methods of examining oculomotor disturbances are outlined, including monocular rotations (ductions), and tests to differentiate between muscular deficiencies and opposing forces. Techniques for identifying the site of a rotational restriction are described, followed by approaches to measuring ocular deviations in diagnostic positions. The concepts of muscular overactions and underactions are analyzed before introducing the concept of diagnostic muscle pairs. Classical knowledge about deviations caused by deficient or restricted muscle actions reinforces the theory of distribution of rotational ocular muscles by diagnostic pairs. For vertical deviations, “underactive” muscle pairs must be separately matched (e.g., RSR with LIR, RIO with LSO). Since vertical recti exert stronger vertical actions than oblique muscles, head tilts are recommended to enhance stress on both pairs, mainly by additional stimulation of oblique muscles. Classical diagnostic directions then align with the objective horizontal plane. The article concludes with peropertative oculomotor testing and a broad protocol for evaluating oculomotor imbalance.

Keywords

(Part II): Ocular rotations; Ocular translations, Contractions, Relaxations, Plane of muscular action; Torque; Lever arm; Sherrington’s law; Hering’s law; Asymmetrical convergence; Isotonic contraction; Isometric contraction; Isotonic relaxation; Isometric relaxation; Active forces; Passive forces; Dissipative forces; Selective muscular functions; Pulleys; Surgical procedures; Muscular transpositions; Bifid transpositions

(Part III): Extraocular muscles; Muscular elasticity; Rotational restrictions; Ocular fixation; Measurement of deviations; Prism-diopter; Unit of measurement; Subjective measurements; Ductions; Muscular overactions; Muscular underactions; Diagnostic positions; Head tilt; Spring-back rotations

PART II: ACTIVE, PASSIVE, AND DISSIPATIVE FORCES

A brief revision of the concept of motion and its cause

Motion (or movement) is the concept by which an observer registers a change in the position of a body (i.e., the displacement of matter) in space. Motion takes time; hence, it is now generally defined as a continuous change in the position of matter in space–time. It is one of our most primitive acquired notions and, arguably, one of the most representative landmarks of how we understand and expand our knowledge of the Universe.

For centuries, the Sun was regarded – beyond of any doubt – as moving in the heavens, while the Earth was considered perfectly static. Later, these conceptions were inverted, and today we accept that both the Sun and Earth are in motion. What changed was not their actual motion, but rather the reference point (in space and-or time) from which their movement was considered.

For example, inside a moving car, if a smartphone is released, the observer sees it falls in a vertical path. To the smartphone itself, the descent is registered as static (the registered movements are of surronding objects), while to an outside observer it follows a parabolic trajectory. These three different descriptions of the same phenomenon highlight that motion is always relative to the frame of reference (or “point of view”) from which it is observed.

The properties of motion are studied in kinematics, which deals with velocity (the relationship between the amplitude of displacement in space and the time spent) and direction (the succession of positions that define a trajectory). The cause of motion is a force, a physical entity that not only initiates movement (providing velocity and direction) but also modifies it by increasing velocity (acceleration), decreasing it (deceleration), preventing it, or stopping it. In other words, the existence (or absence) of motion, as well as its variations (in amplitude, speed, or direction), depends on forces acting on the body.

These principles form the foundation of Newtonian mechanics, which applies to ordinary bodies but not to very small particles (molecules, atoms, subatomic entities). Mechanics has two main branches, statics, which refers to objects “at rest” (equilibrium of forces), and dynamics, which refers to moving objects.

Matter resists being moved; it has a property – “inertia”– that opposes applied force. The amount of inertia is determined by the body’s mass (its quantity of matter). A body’s resistance to being lifted, or the force it exerts on a supporting surface, corresponds to its weight, which counteracts the Earth’s gravitational pull. Similarly, when a force is applied horizontally, friction arises between the body’s surface and that of the support. These cases illustrate Newton’s Third Law of Motion: Every action force is opposed by an equal and opposite reaction force.

The First Law of Motion (law of inertia), first formulated by Galileo, and later generalized by Descartes, states that if no force acts on a body, its state of motion or rest will not change (*1). Thus, a body in uniform motion will maintain the same velocity unless acted upon a force. There is no essential difference between a body at rest (zero velocity) and one moving with constant velocity.

The Second Newtonian law states that a force causes a variation in velocity that is, an increase (acceleration) or decrease (deceleration) in a body’s velocity. Such a variation (a) is directly proportional to the applied force (F) and inversely proportional to the resistance (inertia) offered by the body’s mass (m, a measure of inertia), expressed as a = F/m.

In the case of rotational motion, instead of “linear acceleration” (a) and “linear (or tangential) velocity” (vT), one uses “angular acceleration” (aa) and “angular velocity” (ω). These are related as (a/aa) = (vT/ω) = d (*2), where d is the “lever arm”, or the distance between the point where the force is applied and the body’s center of rotation (center of mass, the point where the entire mass of the body is considered to be concentrated).

How the eyes move

The first paper of this trilogy began with the question of why the eyes move: Without ocular displacement the visual field would be restricted to a small, fixed frame of space. The present paper addresses how the eyes move.

There are two basic types of eye movements, both caused by forces, which may be classified as internal (belonging to the oculomotor system) or external. The first type – eye rotations – involves movement relative to a “fixed” reference frame (the orbit) and is of special interest to ophthalmologists. Ocular rotations are caused by the six ocular (“extraocular”) muscles. (Although the term “extraocular” is widely used, it literally means “outside the eye”, which technically applies to all body’s muscles – except the “intraocular” group. Thus, the term should be used cautiously when referring specifically to ocular muscles.) However, because their amplitudes are limited, full exploration of visual space also requires the second type of ocular movement, ocular translations, in which the eye as a whole moves relative to another reference frame.

Internal forces (those of the rotational ocular muscles) may also cause ocular translations, but these are usually so small that they can be neglected for ophthalmological considerations. Ocular translations (caused by external forces acting on the oculomotor system) are, essentially, displacements of the orbits that is, of the head relative to the body, and/or of the body relative to an external frame of reference in space. Such displacements may occur in any spatial plane (commonly described as horizontal, sagittal, or frontal), either as a rotation around an axis (perpendicular to the plane) or as a translation along it.

For example, orbital (head) rotations relative to the body, produced by neck muscles, occur around the vertical axis (perpendicularly to the horizontal plane) when the head turns right or left(*3); around the transverse axis (perpendicularly to the sagittal plane), when the head rotates up or down(*4); and around the longitudinal axis (perpendicularly to the frontal plane) when the head tilts toward the right or left shoulder. Proper orbital (head) translations (orbital displacements along the trunk’s axes) are also possible, but they have small amplitudes because the head is relatively “fixed” to the neck.

Although head rotations may reach large amplitudes, they are nevertheless limited. Additional ocular translations may result from orbital (head) translations produced by body displacements relative to the ground, either by rotation or translation. Trunk rotations may occur around the vertical axis (turning to the right or left), around the horizontal (or transverse) axis (bending forward or backward), or around an axis perpendicular to the frontal plane (inclining to right or left). Body translations (e.g., walking forward or backward, shifting sideways, climbing or sitting) complete the possibilities. Thus, body movements (rotations and translations) combined with orbital (head) rotations and translations, together with intrinsic ocular rotations, allow visual access to any region of the “visible” space.

Common movements of the body also depend on muscular forces, so it is not entirely incorrect to state that contraction of the triceps surae muscle (the gastrocnemius and soleus, responsible for plantar flexion) can influence vision (e.g., enabling the eyes to be elevated to look over a wall). However, the body may also be displaced in space by external means such as a car, a boat, or elevator. In such cases, ocular translations may occur independently of muscular forces.

Muscular forces: Causes and consequences

A muscle is essentially an “elastic” structure that can change its dimensions – usually its length – through two complementary components: “active” units (sarcomeres) and “passive” yet flexible (extensible) tissues. Sarcomeres respond to neural stimuli (“commands”) by altering their length, a process made possible by both, their proper elasticity and that of the surrounding tissues. When the sarcomere shortens (thus pulling adjacent structures), the process is called contraction. Conversely, when neural stimuli induce lengthening of the sarcomere, allowing it to return to its original state or push adjacent structures, the process is called relaxation.

A contraction (or its counterpart, relaxation) is defined as the activation of tension(*5) that is, an increase in force. If the developed force is opposed by another of equal magnitude, the muscle length does not change; these are termed isometric contractions (or relaxations). If the applied force results in a change in muscle length, the process is isotonic. Unless otherwise specified, the terms “contraction” and “relaxation” in this paper refer to “isotonic” activity that is, variation in muscle length.

From a mechanical perspective, the action of a muscle (contraction or relaxation) involves variations in muscle length determined by the distance between its insertion (I) on the eye’s surface (which moves with eye movements relatively to the orbit) and its origin (O), a fixed point outside the eye (immobile during ocular rotations). A net increase in muscular force shortens the muscle length and pulls the scleral surface toward the origin (force directed from I to O), producing rotation. Conversely, when tension decreases (during relaxation) the force is directed from O to I.

Three anatomical points are fundamental for understanding ocular rotation: I (ocular insertion, where force is applied), O (muscle origin), and C (the center around which ocular rotations occur). While O and C can be considered fixed relative to orbital reference points (at least in “pure” ocular rotation), I moves with eye movement. At any given moment, however, I, O, and C lie in the same plane, termed the plane of muscular action, with a perpendicular “axis” through C around which rotation occurs. The effect of muscular force is distributed across the three spatial planes according to the projection of this “axis” (vector) in each. Because the effect depends on the position of I, the distribution of muscular force may change during ocular rotation (see also, “The relatively large extension of the muscular insertions”).

A) Torque: Quantitative effectiveness of a rotatory force

The magnitude of ocular rotational movement in each spatial plane – that is, the torque plane (T, also called “moment of force” or “force moment” ) – depends on three factors: (1) the net applied force (F) determined by the neural command, (2) the angle of action (α), and (3) the distance (d, or “lever arm”) between the point of force application and the center of rotation. This relationship is expressed by the following equation:

T= F.d.sin α (F.I)

Because each rotational ocular muscle inserts on the scleral surface, the distance to the center of rotation corresponds to the eye’s radius of curvature (r). Maximal rotational efficiency occurs when the applied force is tangential to the ocular surface, that is, perpendicular to the eye’s radius of curvature (α=90°, sin α=1). In this case, torque (T=F.r.1) directly reflects the muscular force of contraction or relaxation. This torque is distributed across the three fundamental spatial axes according to the projections “of the axis”(vector) – perpendicular to the plane of muscular action.

Determining the position of this vector in space – and, consequently, the rotational components of a muscle’s contraction in the horizontal (H), vertical (V), and frontal/torsional (T) planes – requires theoretical consideration of (a) the coordinates of the muscle’s origin O (xo, yo, zo); (b) those of its insertion, I at the primary gaze (xi, yi, zi); and (c) their information after a rotation defined by components H, V, and T in each (2-4).

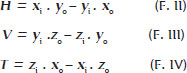

In the primary gaze position (H = V = T = 0°), the equations for the horizontal, vertical, and torsional components of muscular pull are expressed as follows:

Results for H, V, and T may be positive – corresponding to adduction, sursumduction, and excycloduction – or negative, corresponding to abduction, deorsumduction, and incycloduction. These outcomes reflect the specific actions of one of the six rotational ocular muscles. In principle, any “positive” or “negative” rotation (H, V, or T) beginning from the primary gaze position, can be maximally obtained by an appropriate positioning of the applied force (Figure 1).

B) The arc of contact

It is not theoretically convenient that the maximal rotational efficiency of a force be limited to a single point of tangential application on the scleral surface, but rather that it extends over a larger superficial area. In other words, the muscle must lie over the eye, that is, with an arc of contact (Figure 2).

Therefore, although the disposition of ocular muscles to produce eye rotations could in theory be entirely free (Figure 1), the requirement of large arcs of contact limits some alternatives which could otherwise be troublesome. For instance, the existence of a muscle (arc of contact) passing by the anterior or posterior parts of the eye makes the muscle paths (from insertions I to their respective origins O) parallel to the x-orbital axis (Figure 1, second and fourth columns from the left) which should be avoided. In addition, since the anterior part of the eye must remain free to transmit light, the origins of such muscles should be close to the posterior segment. The actual structure of the human orbit – as the result of phylogenetic evolution – appears to be the natural answer to such needs. In the horizontal plane, a close similarity is observed between the “ideal” (Figure 3a) and the actual (Figure 3b) muscular dispositions

In fact, the six rotational ocular muscles are arranged in pairs to provide, mainly, actions in each of the three spatial planes. If, by approximation, one assumes for the horizontal recti zi=0=zo, equation F.II remains unchanged, but Equations F.III and F.IV give V=0 and T=0. That is, horizontal rotations (H), adduction and abduction, are primarily given by the medial rectus muscle (MR) and the lateral rectus muscle (LR), respectively.

If, also, for the vertical recti, one considers xi=0=zo, then H=–yi . xo, V=–zi .yo, and T=zi . xo. Considering only the absolute dimension of a measurement (its modulus), not its sign, since (for the coordinates for a vertical rectus muscle), yo > xo, then V>T; and as zi>yi, then T>H. Therefore, for the vertical recti, V>T>H. By a similar procedure for the oblique muscles (coordinates in Figure 3), T>V>H. Thus, the vertical recti and oblique muscles are considered cyclovertical muscles, although vertical rotations are predominantly produced by the vertical recti (sursumduction or elevation by the superior rectus muscle, SR; deorsumduction or depression by the inferior rectus muscle, IR), while cycloductions (frontal plane) are mainly produced by the oblique muscles: excycloduction (by the inferior oblique muscle, IO) and incycloduction (by the superior oblique muscle, SO).

C)The Sherrington’s law

The (approximately) parallel forces of each pair of the external ocular muscles act in opposite directions, so that, to maximize rotational efficiency in a specific orientation (clockwise or counterclockwise), they require a special command. Therefore, when a muscle is stimulated for contraction (i.e., to initiate a force), its opponent receives a command for relaxation. This is the principle of a conjugated or binary mechanical system, in which the two generated forces act with the same orientation. Such a neural relationship, whereby contraction of a muscle (the “agonist”) accompanied by synchronous reciprocal relaxation of its pair (the “antagonist”), is Sherrington’s law of reciprocal innervation.

In principle, it might be expected that the variation of forces in a pair of agonist-antagonist muscles would be perfectly symmetrical relative to a “median” position (the primary position) but inverted - that is, the greater the action of one, the smaller that of the other. In addition, the variation of forces due to reciprocal innervation for a desired result (e.g., adduction) and the respective inhibition of the antagonist (relaxation of abduction, therefore allowing more adduction) might be expected to be perfectly linear in the case of a perfectly elastic system. This leads to a graphical and pictorial representation of such forces (Figure 4).

D) Isometric and isotonic contractions and relaxations: Hering’s law

Binocularly conjugated eye rotations (versions) in each direction are commanded to be symmetrical, according to Hering's law. If the muscles were equal in responding with equivalent forces, their innervation stimuli should also be equal. For muscles with different responses to the same amount of binocular rotation, the stimuli must be “proportional” to guarantee equivalent rotations. In any case, “Jusional” adjustments of the required rotational amounts are added, if necessary.

For binocular vision directed to points in space requiring different amounts of rotation in each eye - or for a “final” fusional correction according to Hering's law - disjunctive binocular motions (vergences) are provided. Therefore, vergences and versions may be summed, sometimes resulting in no rotation in one eye and asymmetrical convergence In the other (Figure 5). In the eye without movement, isometric contractions (“co-contractions”) occur.

The greater the asymmetrical convergence, the greater the increase in stimuli to the horizontal recti of the stationary eye, as confirmed by electromyogram(6).

A similar phenomenon is seen in Duane's syndrome. In type 1, affecting the right eye, if levoversion is commanded, the RMR receives a normal stimulus to contract (adduction), while the RLR, instead of relaxing, is also abnormally stimulated to contract. The simultaneous increase of forces in both horizontal recti produces a small posterior translation of the eye (enophthalmos, which involuntarily narrows the palpebral fissure) and an increase in intraocular pressure171, as the eye is compressed against orbital contents.

How the eye stops moving

A schematic explanation of how the eye moves -by an imbalance of oppositely acting muscular forces of a simple binary system (Figures 4 and 5) - leads to the possibility that, once a rotation is started, it would remain perpetual. On the contrary, however, after a relatively short rotation (maximally around 50°), the eye is braked to a stop. This is not usually due to a new (voluntary or reflex) neural command, though, as seen in asymmetrical convergence and Duane's syndrome, active forces may be stimulated to prevent ocular motion (Figure 5). Of course, braking forces could also come from neural commands, but this would appear contradictory to Sherrington's law, or at least suggest a more complex and uneconomical arrangement of stimuli to “go but stop”. In fact, what limits ocular movement is a natural consequence of the very cause that enables rotation: the elasticity of the muscles and their surrounding structures. Muscular stretching (particularly of the antagonists) absorbs kinetic energy of an ocular rotation and imposes opposing forces, bringing the system back into balance.

The passive forces (of the conservative system)

During an ocular rotation, elastic structures are stretched while others are compressed but both absorb kinetic energy and accumulate it as potential energy. Muscular fibers, their surrounding and intermuscular membranes or fascias, conjunctiva, nerves and blood vessels all act as “elastic” structures, but the muscles are the most important.

If the oculomotor system behaved as a perfect (linear) elastic system, passive forces (from stretched and compressed tissues) would increase at the same rate as the variation of active forces. In a conservative system, the active forces that initiate rotation are opposed by passive forces from elastic tissues; kinetic energy is absorbed, and the rotation stops. Thus, the extent of a rotation is limited by the balance between passive and active forces (Figure 6).

Although periocular structures (including the muscles) could theoretically absorb energy whether shortened (like a compressed spring) or elongated (like a stretched rubber band), they behave “passively” mainly as elastic bands. Experimental data support this: After conjunctival opening (e.g., nasally) or disinsertion of a muscle (e.g., the medial rectus), the eye deviates to the opposite side (temporally)18-101. If the conjunctiva or muscle had accumulated energy to push the eye (like a compressed spring), removal of that push should result in adduction. Instead, abduction occurs. Therefore, the schematic representation in Figure 4 can be improved by considering the balance of forces at the end of a rotation (Figure 6) as due to periocular structures - mainly the muscles - acting as elastic bands.

Two basic mechanical types of eye displacement between two points in space may be considered. One is slow, a smooth pursuit movement; the other is rapid, a saccadic movement. These are controlled by independent neural systems and have different mechanical explanations. The smooth pursuit movement (velocities about 30 - 50°/s) (11) occurs during continuous fixation on a rectilinear target displacement. It depends on a progressive increase in contraction of the agonist muscle and relaxation of its antagonist, automatically accompanied by an increase in opposing passive forces. The saccadic movement is produced by a burst of activity in the agonist muscle and complete relaxation of its antagonist. This generates very high velocities (large saccades of about 90° may reach peak velocities near 1000°/s), yet the movement is properly limited by passive forces to the required extent. A similar saccadic rotation can also occur if, in a stable eye position (e.g., + 40° or -40°) maintained by an external force during general anesthesia, the absorbed energy in stretched tissue (muscles) is released.

The dissipative forces

As shown earlier, although a static eye is necessarily represented by a balance of forces, the state of the muscles - whether more activated (contracted) or less activated (relaxed) - differs for each position of gaze: The greater the required rotation (e.g., adduction or abduction), the greater the net muscular activity needed. For example, the eye position of +40° (adduction) (Figure 6a) corresponds to strong stimulation of the RMR (+ + + +), while stimulation of the RLR is reduced to 0. The system, however, remains precisely balanced by equal and opposite passive forces. As long as this command for activation is maintained,, the eye is held immobile at +40°. When the command to the RMR ceases, the balance of forces is lost. Inactivation (relaxation) thus acts as a reciprocal “activation” that initiates a returning saccadic rotation toward the primary position.

If no other forces acted, the system would continue in perpetual harmonic motion, like a pendulum (Figure 7). On the contrary, after a rapid “return” toward the central position, the rotation stops (Figure 8). During contraction, progressive activation of a muscle, combined with reciprocal inactivation of its antagonist, is countered by increasing passive (resistive) forces in stretched tissues (Figure 8a-c). Part of the command energy is converted into motion (kinetic energy), part is stored as potential energy in stretched periocular structures, and the remainder is lost - either dissipated as heat through friction or through inelastic deformation of viscous periocular components (e.g., conjunctiva, soft tissues, or the so-called “check ligaments”).

If the muscle maintaining a stable position after rotation is relaxed (Figure 8d), the stored potential energy in stretched structures initiates a “returning” rotation. As the rotation progresses, muscular tonicities ( + ) are gradually restored, passive forces of shortened structures decrease (red P), while those of stretched structures increase (blue P). However, part of the energy is dissipated (Figure 8e), so the cycle ends in a stable position (figure 8f).

Under general anesthesia, when no active forces ( + ) are present, a similar scheme can be considered (the spring-back balance test, studied later)18’121. In both active (neural) and passive (externally induced) conditions, the absorption of received energy has two components: (i) accumulation by elastic structures -the conservative system -, and (ii) dissipation through inelastic deformation or frictional heat - loss, the dissipative system.

A final schematic view of force distribution during ocular rotation can now be offered. Although the oculomotor system is basically “elastic,” it does not behave as a “perfectly” linear (conservative) system. Viscous and inelastic structures dissipate part of the received energy. During muscle contraction, a portion of energy is spent as heat or against inelastic resistance; only part results in motion. Consequently, progressively greater energy is required for progressive equal increments of rotation - for example, the energy to move the eye from 0° to 20° is less than that needed from 20° to 40°.The muscle's mechanical behavior is better described by an asymptotic curve (Figures 9 and 10)(13).

The relatively large extension of the muscular insertions

A muscle is composed of numerous fibers that extend over the scleral surface in a line of insertion measuring approximately 9-11 mm. The imaginary frontal circle along which the insertions of the recti muscles are distributed has a diameter of about 19.5 mm (broken blue line, Figure 11), corresponding to a circumference of about 61.3 mm. Therefore (4 x 10)/61.3 ~ 65% of this circle is covered by the recti muscles insertions, a relatively large extension.

Although the action of an entire muscle can be simply defined as that of a single fiber pulling from the median point of the extended insertion, each of the multiple fibers produces distinct and specific torques. These may, in part, oppose the action of the remaining fibers. Consequently, the same muscle may exhibit rotational effects of different qualities and/or magnitudes. For instance, in the horizontal plane, the SR and SO muscles are defined as having the properties of adduction and abduction, respectively (functions attributed to the fibers of their median insertions). These actions are particularly prominent in the medial fibers of the SR and the posterior fibers of the SO (Figure 11a). In contrast, the lateral fibers of the SR (and of the 1R) and the anterior fibers of the SO muscle are expected to have no horizontal action - or, if present, to contribute to abduction and adduction, respectively. 1n other words, lateral and medial fibers of the superior rectus, as well as anterior and posterior fibers of the superior oblique have opposite actions

The anterior halves of the SO mainly produce incyclotorsion (and ocular depression). Thus, sectioning these fibers, while weakening the muscle overall, can indirectly and relatively favor abduction by liberating the action of the posterior fibers. Selective sectioning of superior fibers of the horizontal recti (MR and LR) favors depression, whereas selective sectioning of their inferior fibers favors elevation.

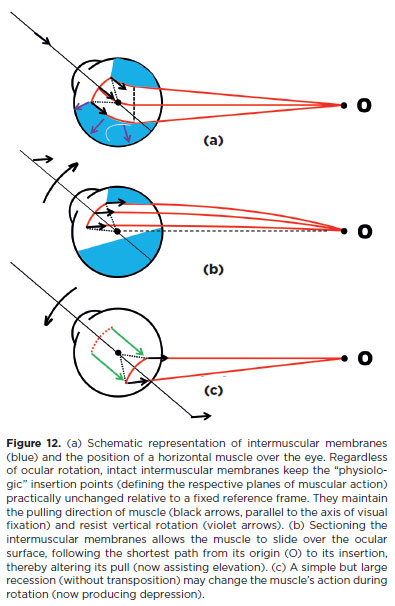

Intermuscular membranes - Pulleys(14)

1f, during ocular rotations, the rotational ocular muscles were completely free to slide over the eye, they would follow the shortest path between their scleral insertions and their origins (Figure 12b). However, they are enclosed by membranes (fasciae) that interconnect to form a continuous covering. As a result, the pulling directions of a muscle contraction remain almost constant regardless of eye position, as though the muscles passed through pulleys. This maintain the same plane of action as in the primary position of gaze (Equations F.11-1V). Therefore, even a simple section of the intermuscular membranes can alter a muscle’s action. For the same reason, a recession may also modify the expected muscle action. For example, after sectioning the intermuscular membranes, a horizontal muscle may act as an elevator during elevation (Figure 12b); following a very large recession the same muscle may become a depressor (Figure 12c).

Changing actions of external ocular muscles

The majority of medical procedures intended to modify the actions of the rotational ocular muscles are surgical.

These are classically divided into two broad groups. The first, quantitative, aims to increase (“strengthen”) or decrease (“weaken”) the overall action of a muscle without altering the distribution of muscular forces across spatial planes. Strengthening procedures include resections, plications (shortening), and advances of the insertion (stretching). Weakening procedures include recessions (elongation and slackening), partial or total sections of muscle or tendon (myotomy or tenotomy), with or without excision (myectomy or tenectomy). These may also be “compensatorily” combined such as a “resection” with an equivalent “recession” (Figure 13, the “fadenoperation”).

The second group, qualitative, aims to change the spatial distribution of muscular action (e.g., selective section of muscle fibers, transpositions). These procedures decrease action in one (or two) plane(s) while increasing it in the others(15).

Together, these techniques represent both the science (when, which muscles, and how much to operate) and the art (the manner of execution) of surgical treatment or strabismus and related disorders (Figure 13).

Muscular transpositions

The distribution of a muscle's rotational effect across the spatial planes changes when its plane of action is transposed. This principle is widely applied in surgical treatment of oculomotor disturbances.

It is well established that if the MR muscle is reinserted below the horizontal plane, it regains its original horizontal disposition and better adductive effect when the eyes are elevated; conversely, it becomes less effective in depression. Stronger action in elevation (greater convergence) and weaker action in depression produces an “A” pattern. Thus, transposition of the MR below the horizontal plane is designed to correct a “V” pattern. Conversely, reinserting the MR above the horizontal plane helps correct an “A” pattern.

A similar logic applies to LR transpositions: to correct a “V” pattern (i.e., by producing an opposite “A” pattern), divergence must be greater in depression when the LR muscles are in their original horizontal disposition. Therefore, the LR muscles should be transposed above the horizontal plane. For the vertical recti, the prevailing principle is that medial transpositions favor adduction: medial transposition of the SR corrects a “V” pattern, while that of the 1R corrects an “A” pattern. Conversely, lateral transpositions of the SR and IR help correct “A” and “V” patterns, respectively.

Similarly, horizontal recti may be displaced vertically to correct vertical deviations, while horizontal transpositions of the vertical recti can be used to address horizontal deviations.

A widely used procedure is transposition of the SR and 1R to the lateral side, either as total transposition (Hummelschein's proposition)1161, partial transposition, or one of its variants. A mechanical effect preventing the opposite rotation (adduction) may reasonably be expected, but not the addition of an “active” rotational effect to replace a lost movement (abduction). Neural control remains unaltered(17): The vertical recti do not acquire the ability to produce abduction. The SR contracts during elevation and the IR during depression, regardless of their insertion site. Thus, after transpositions of the vertical recti to the lateral side, abduction occurs only when elevation or depression is required.

For example, if the transpositions are performed on the left eye, a levoversion (left-eye abduction) provides no stimulus to the silent vertical recti (LSR and L1R). During dextroversion, activation of LSR and L1R may occur as synergists of left adduction, further restricting adduction. In summary, even if the surgery is well executed, the active forces of the transposed muscles may result in binocularly abnormal (disjunctive) rotations. Passive tensions of the transposed muscles can, however, contribute to restoring abduction, though at the cost of limiting adduction, much like elastics or springs)(*6). To avoid the adverse effects of active vertical recti transposition, a mechanical alternative for correcting esodeviation due to LR paralysis is simply to shorten (resect) the elastic tissues of the paralyzed but mechanically intact LR muscle.

Finally, transposition may also serve to partially or completely neutralize the action of a muscle while leaving it inserted in the eye(22). For example, suppose a rectus muscle is split into two halves and each is reinserted symmetrically on opposite sides of its original plane of action. 1n that case, the effective insertion shifts to an imaginary point inside the globe. The lever arm for torque generation is then shorter than the ocular radius of curvature. Torque becomes null when the “effective” insertion coincides with the ocular rotation center, eliminating rotation by that muscle. While technically demanding, partial symmetrical transpositions (reducing lever arm length and decreasing the angle of force application) are ease to perform, effectively weakening the muscle (Figure 14).

For instance, a horizontal muscle such as the RLR (Figure 14) will have its abductive power reduced, while the vertical and torsional effects of the two symmetrically placed halves cancel each other out. If each half is reinserted at the superior and inferior poles, the effective insertion coincides with the center of curvature, rendering the lever arm null in primary gaze (as well as in any other ocular position in the horizontal plane).

A TRILOGY OF THE OCULOMOTOR SYSTEM PART III - DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Diagnostic complexities of the oculomotor system

Twelve ocular muscles-each with specific actions, which may vary depending on the fibers involved and on the eye's position relative to its orbit-are commanded by three pairs of cranial nerves and a complex neural organization. Together, they coordinate the spatial and simultaneous orientation of the principal gaze axes of both eyes so that vision is directed to any point in space requiring attention. Broadly, this is the structure and purpose of the oculomotor system-so refined and with such high demands-that it is easily affected by various dysfunctions, some of which have inconspicuous causes and are therefore difficult to detect.

As previously described, the oculomotor system organizes rotational ocular muscles functions in pairs. Thus, even for a “simple” rotation, such as rightward movement of the right eye, contraction of the right lateral rectus muscle (RLR) and relaxation of the right medial rectus muscle (RMR)-Sherrington's law-are required(*7). For the left eye to conjugate in this same “right gaze,” coordination between contraction of the left medial rectus muscle (LMR) and the RLR-Hering's law-is also necessary, with Sherrington's law simultaneously applying to the left eye. Finally, if this “right gaze” is directed at a finite distance, “fusional” (binocular) convergence is also required. In summary, even a simple abduction of the right eye depends not only on RLR contraction but also on RMR relaxation, though other simultaneous commands for the left eye are required.

Therefore, even for a “simple” ocular rotation, a defective result (partial or complete absence of rotation) may have different causes (Figure 15):

a) faulty stimulation of the agonist muscle (a true neural paralysis), such as the right eye cannot look right because of RLR paralysis;

b) faulty muscle response (an inelastic or “fibrotic” muscle, also-wrongly-classified as a muscular “paralysis”);

c) faulty relaxation of the antagonist muscle (e.g., limited right eye adduction due to persistent RLR contraction, as in Duane's syndrome-a defective Sherrington's law of the right eye, type 1). Such neural defects are now classified as congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders (CCDD);

d) excessive resistance of the antagonist muscle to stretching (lack of elasticity), as in Brown's syndrome.

In general, ocular rotation results from the simultaneous (active or passive) actions of all rotational ocular muscles of an eye. For example, consider downward gaze. Contraction of the inferior rectus muscle (1R) is required, accompanied by relaxation of its antagonist, the superior rectus muscle (SR). However, the 1R also produces adduction and extorsion. To counterbalance these, the lateral rectus muscle (LR) contracts (with simultaneous relaxation of the medial rectus muscle, MR), and the superior oblique muscle (SO) acts (with relaxation of the inferior oblique muscle, 1O)(*8).

Finally, strabismus treatment seldom addresses underlying causes; in most cases, it only corrects consequences, which explains the frequency of recurrence. For this reason, the best diagnostic approach lies in gathering detailed data about the effects of oculomotor disturbances-namely, studying deviations and their manifestations, or in other words, understanding ocular mechanics. 1n practice, a well-structured examination of oculomotor forces-active (muscular responses), passive (conservative), and dissipative (rotational restraints from periocular structures)-is essential. These examinations constitute diagnostic tests, each with different foundations and objectives.

General principles and guidelines of treatments

Disturbances of the oculomotor system are both causes and consequences of visual dysfunction.

Since good visual function is the natural finality of the oculomotor system, it takes precedence as the primary purpose of treatment in strabismus and related disorders. 1n some cases, poor monocular vision (e.g., from a macular scar due to choroidoretinitis or macular retinoblastoma) cannot be corrected, nor can good vision be restored. 1n other cases, poor vision (such as amblyopia in children) is the consequence of strabismus and treatment of vision becomes the absolute priority. Even in the absence of monocular visual loss, strabismus must be treated early to prevent loss of good binocular vision or to correct diplopia. 1n summary, all cases of strabismus are associated with some degree of visual disturbance.

Therefore, examinations and management of monocular and binocular visual status must take priority over those of the oculomotor system. The only exception is when strabismus is secondary to a life-threatening condition (e.g., brain tumor), which demands urgent attention. Thus, for reasons of importance rather than neglect, examinations of vision are not addressed here.

For treatment of oculomotor imbalance, the goal is to achieve a “complete” restoration of binocularly adequate eye positions (visual axis alignment) and movements. However, in some cases, although sa tis-factory eye alignment is achieved, ocular rotations cannot be fully restored. Muscular paralysis (“dead” muscles) and restrictive conditions are the most common causes. Once a rotation is lost, it can be partially compensated, for example, by anchoring the eye in a desired position through resection of the paralyzed muscle, although such a result (or of any other presently available procedure) inevitably reduces movement in the opposite direction. Restrictive scarring can also be surgically removed, though recurrence is common. 1n some cases, alignment in the primary position of gaze may be the only achievable result, with visual exploration of space then provided by head and body movements.

All rotations are important, but ocular elevation is the least essential and may be sacrificed to preserve other movements. 1n contrast, downward gaze is critical and should be preserved whenever possible. For example, achieving proper alignment in downward gaze, even at the cost of a slight hypotropia in the primary position, may be an excellent outcome. This can often be compensated by a mild chin elevation-a “proud,” socially acceptable head posture (*9).

The state of ocular fixations (head and eye positions)

As noted earlier, vision intrinsically depends on ocular motion. These range from fine, imperceptible micromovements (essential for detailed visual discrimination) to large eye rotations and translations (necessary for spatial exploration). This intimate relationship between vision and ocular motion, which cannot be dissociated, is reflected in two main conditions examined in practice:

1. The state of apparent absence of ocular movement, that is, fixation (attendance to the object of visual attention).

2. The amplitude and quality of eye movements, whether monocular (ductions), binocularly conjugate (versions), or binocularly disjunctive (vergences).

Thus, the most basic information about the oculomotor system-and, simultaneously, about fine visual discrimination-comes from examination of fixation (i.e., eye position or direction), both in temporal and spatial terms.

A) Stability

The temporal stability of fixation is essential, since gaze on an object must be continuously maintained for fixation to “exist.” Poor fixation, manifested as vague or imprecise gaze and an inability to maintain steady attention, reflects impaired vision due to poor ocular reception, neural deficits (e.g., blindness), or severe psychomotor abnormalities. For examination of stability, the subject must attempt voluntary fixation, even if unsuccessful. Rhythmic, involuntary instability of fixation (nystagmus) is another indicator of reduced visual acuity. Minute physiological eye movements are not perceptible to the naked eye.

B) Position (direction)

The expected spatial state of fixation is defined as the alignment of the visual axis (formed by the ocular sagittal and horizontal planes) with the orbital longitudinal axis (“straight-ahead” axis, also formed by the sagittal and horizontal orbital planes)(* 10)(23,24). When this coincidence is not achieved, an absolute ocular deviation exists, that is, deviation of the eye relative to its orbit. Absolute deviation may be due to limited rotation (from paralysis of an agonist muscle or excessive action of an antagonist, whether active “over-action” or passive restriction from scar tissue), or may occur as a compensatory mechanism in nystagmus. Absolute deviation of the fixating eye (the preferential or unique eye) manifests as an abnormal (or “vicious”) head posture. Therefore, correction of abnormal head posture requires correction of the underlying absolute ocular deviation-typically by surgery on the affected eye or its muscles-regardless of whether the other eye is blind, amblyopic, or free of strabismus. Any deviation of the poorer eye relative to the better eye must be considered separately.

C) Ocular deviations

Ocular deviation refers to the difference between the expected and actual direction of fixation of an eye relative to a reference point requiring attention. In theory, both eyes could be simultaneously deviated from a reference point (e.g., strabismus in a blind individual). In practice, however, at least one eye is generally aligned, while the other may be deviated or not. Determining the reference point for visual axes is crucial; without it, no conclusion about deviation can be drawn, although ocular positions can still be documented (Figure 16).

Measurements of eye positions and deviations

Binocular deviations are measured as the angles formed by the fixation lines of both eyes (ocular positions), whether these correspond to normal vergences, abnormal binocular deviations (“true” strabismus), or intermittent states representing both (heterophoria, or “latent” strabismus). Careful differentiation is required.

A rough estimate of ocular deviation may be obtained using Hirschberg's method(25), which evaluates asymmetries between corneal reflex positions when a “luminous point” is placed at a large distance. Each 1 mm of asymmetry corresponds to ~7° (von Noorden(26) reports 8°). If the reflex is centered in one cornea but lies at the pupillary margin in the other, the angle is ~15°; if at the limbus, ~45°; midway between margin and limbus, ~30°.

In Krimsky's method, the measurement is based on the prism value placed before the deviated eye that centralizes the corneal reflex. It is important to note that the difference between the geometric longitudinal ocular axis and the visual (fixation) axis-the angle alpha-is normally ~3° but may reach 8°.

In clinical practice, exact measurement of corneal reflex position relative to the visual axis is not possible. For the fixating eye, coaxial alignment of the incident light and corneal reflex defines the visual axis. However, for the fellow eye, the reflex is measured from a “dystopic” direction (the visual axis of the fixating eye), introducing parallax error. Moreover, the correct estimation for one eye does not guarantee the same for the other. In summary, Hirschberg's and Krimsky's methods provide only approximate “objective” measurements, reserved for cases where cooperative methods cannot be applied(26).

The preferred unit for angular measurements is the degree of arc (and submultiples: 1=60' = 600"), or alternatively, the radian (rad), with 1 rad = 180°/n. Dennett(27) proposed the centrad (crad), a centesimal part of the radian, where 1 crad=1.8°/n»0.57296°, so 1°»1.74533 crad.

In clinical practice, however, the prism-diopter (A), introduced by Prentice(28), became preferred. Its advantage is that it directly relates separation (x, in cm) to distance (d, in m): 1A =100 x/d.

Since the ratio x/d can be expressed trigonometrically as a = arctan(x/d), conversion between prism-diopters (PA) and degrees of arc (a°) is given by

a = arctan (P/100) (F. I) and, or 100 tan a = P (F. II)

Thus, 1°»1.7455A, or conversely, 1A»0.5729°. The ratio between prism-diopters and centrads for 1° differs by only 0.01%. However, prism-diopters are nonlinear relative to degrees (and centrads). At 10°, the error is ~1%; at 50°, it is ~36.6%; and at 90°, the value become infinity. Hence, arithmetic operations with prism-diopters are unreliable.

Alternative definitions of a “new” prism-diopter unit (Uk)(29,30) have been proposed. The conversion formulas are as follows:

arctan (P/100) = a = k.arctan (U/100 k) (F. III)

Uk = 100. k. tan (a/k) (F. IV)

For instance, if P = 50A, then arctan (50A/100)» 26.565°»46.365 cent-radians, which corresponds to a numerical increase of 50A/46.365 crad of about 7.84%. This error becomes much greater if the sum 50a (»26.565°) + 50A (»26.565°)=133.333A (»53.130°»92.730 crad) is considered. In this case, the difference from the “linear” value increases to about 133.333A/92.730 crad » 43.79%. However, if one considers k=10, using the F.IV for the value of a = 26.535° (when P = 50A), the result is U10=1,000 tan (26.565°/10)»46.398", which corresponds to a difference relative to the value in centrads of about 46.398"/46.365 crad»0.07%. If one considers the double angle (2x26.535°=53.130°), then U10=1,000 tan (53.130°/10) » 92.996" (slightly more than 46.398" x 2 » 92.796"), which compared to the 92.730 crad, gives a numerical difference of about 0.29%. Note also that in prism-diopters, 50A+50A»133,33A (an error of 33.33% on the presumed value of the sum), while with the U10 units, 46.398" + 46.398" » 92.996", an error for the presumed sum of only 0.22%.

Qualification of a strabismus depends on the fixating eye

The type and direction of an eye deviation (strabismus) is defined when “fixation” on an object of visual attention is required separately by each eye. This is obtained by the “cover-uncover test,” in which one may detect a clear dominance of fixation by one eye relative to the other (monocular strabismus) or whether fixation may (spontaneously or artificially) change between eyes (alternant strabismus).

This “qualifying” test is performed when the preferentially fixating eye is directed “straight ahead,” an expression not identical to “primary position of gaze”, though often — but wrongly — considered as such. Fixation is then prevented (by “occlusion”), and the strabismus is classified according to the direction of the ocular movement of the deviated eye-horizontal (eso or exo) or sagittal (L/R or R/L), or a combination of the four possibilities — required to recover visual fixation. Although this test characterizes the type, direction, and “basic angle” of deviation to be corrected, it is not strictly necessary or sufficient for diagnosing the paretic muscle or the site of rotational restriction.

Although seemingly simple (“cover the fixating eye-observe possible movement of the other eye resuming fixation-then uncover”), the test yields alternative results whose interpretation requires solid clinical experience. In principle:

1. If no movement of the uncovered eye occurs, this indicates that the eye either cannot fixate (because of poor vision) or was not previously deviated.

2. If movement occurs, the eye was previously deviated (strabismus). If-when the other eye is uncovered-the eye returns to its former position, the strabismus is “monocular.” If fixation remains with the previously deviated eye, the strabismus is “alternant.”

Although the “uncover” step suffices to determine the type (monocular or alternant) of strabismus, repeating the “cover-uncover” test on the newly fixating eye is recommended. This double examination not only confirms the type and direction of deviation but also suggests which eye is primarily affected. For example, in a vertical deviation L/R (left eye higher than right) of 15" with fixation by the right eye (REF), if, under left eye fixation (LEF):

a) The deviation is 12" but still L/R ^ “comitant” L/R vertical deviation.

b) The deviation decreases to 2" but remains L/R ^ “incomitant” L/R vertical deviation, suggesting paresis of a cyclovertical muscle in the RE (RSR or RIO) or restriction of RE elevation.

c) The deviation increases to 28" but remains L/R ^ “incomitant” L/R vertical deviation, suggesting paresis of a cyclovertical muscle in the LE (LSO or LIR) or restriction of LE depression.

d) The deviation becomes 20" but changes direction to R/L ^ “dissociated (or divergent) vertical deviation” (DVD).

Options (a) to (c) follow the clinical rule that a deviation (ET, XT, R/L, or L/R) is greater when fixation is directed by the eye containing the (most) underactive muscie or rotational restriction.

Measurements of deviation at primary position of gaze, though often used to define type and “basic” angle (with fixation by the preferential eye), are not strictly necessary for diagnosing the paretic muscle or site of restriction.

Advantages and difficulties of subjective measurements

When a deviation is unapparent (absent or inconspicuous), the “cover-uncover” test becomes more complex, since even temporary interruption of fixation (cover step) may evoke deviation. After uncovering, the eye may recover (heterophoria) or not, and corrective movement may go unnoticed. Thus, distinguishing heterophoria from small-angle strabismus may require additional information (e.g., monocular visions and binocular correspondence).

Subjective tests of deviation (depending on the patient's reports) are quantitatively more accurate (able to detect deviations as small as 0.5A) than the cover-uncover test, where deviations of about 2A may escape expert detection. However, discrepancies between objective and subjective measurements of strabismus often indicate anomalous visual (binocular) correspondence. In addition, subjective tests (e.g., binocular positions using Maddox rods) typically yield greater deviations than objective methods, even in normal individuals (heterophorias), likely due to stronger binocular dissociation.

Monocular rotations (ductions)

After testing for deviation at the “basic” straight-ahead position, monocular rotations (ductions) should be examined. Horizontal and vertical rotations are usually ample but limited by check ligaments and periocular structures to about 50°. In practice, most ocular motion results from combined rotations and translations (via head movement), so pure ocular rotations are generally smaller (15°-20°).

As shown in Figure 15, two main causes limit rotation: lack of active force (muscle paralysis, absence of pull) or excessive (passive or active) restrictive force (excess of opposite pull). Active forces are generally strong, so even when deficient, monocular rotations of normal amplitudes may occur. However, small defects of neural command are detected by comparing binocular rotations (versions). Thus, normal monocular amplitude is not proof of normality, as it may occur even in muscle palsy. In such cases, end-point stabilization of an “extreme” rotation fails (antagonist pulls eye back), producing a slow centripetal drift followed by a fast corrective saccade. This corrective phase defines the “direction” of nystagmus. For example, right eye nystagmus in abduction (saccadic to the right) indicates RLR underaction.

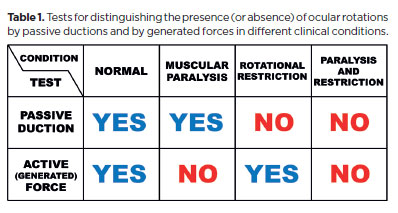

Incomplete or absent rotation (partial or total) indicates underaction, requiring differentiation between lack of active force and restrictive opposition. Paralysis/ palsy (loss of active force) must be distinguished from faulty rotation caused by scar tissue, fibrosis, contracture or passive shortening of antagonist muscle or its overaction (erroneous stimulation, e.g., Duane's syndrome). These differences are resolved by differential tests: the test of generated forces (activeforce)(31) and the passive duction test (Table 1).

The duction and generated force tests are complementary: the duction test is “positive” for restriction (“negative” for paralysis)(*11), whereas the force test is “positive” for absence of forces, or paralysis (“negative” for restriction; Table 1)(*11).

Strictly speaking, the (passive) duction test-evaluating whether ocular rotation in the expected direction can occur with external traction assisting the subject-is a specific proof of rotational restriction. If no rotation occurs, a restrictive impediment is confirmed. Conversely, if rotation does occur, restriction is excluded. In this case, one could argue that, as restriction is denied, the absence of ocular motion (without external help) indicates muscular paralysis. However, while the diagnosis of paralysis may be inferred as a “negative” proof of absent rotational restriction, the test cannot serve as a “positive” proof of paralysis.

The same reasoning applies to the test of generated forces: It may indirectly suggest restriction (if an evoked force is present), but it is specifically designed to confirm or exclude muscular paralysis. Summarizing: if an eye is fixed in adduction, the (passive) duction test may confirm a rotational restriction but does not exclude an associated paralysis of the LR. Conversely, the test of generated forces may confirm paralysis but cannot exclude the possibility of a superimposed rotational (mechanical) restriction.

The (passive) duction test can be performed in an alert subject or under general anesthesia, while the test of (active) generated forces requires a cooperative subject. Alertness and cooperation thus limit both tests in children and certain patients. In practice, indirect clues about generated forces may be observed clinically. A muscular rotational activity in a generated force test is recognized when the examiner feels a sudden pull through forceps holding the eye opposite to the intended movement (e.g., for testing abduction force, the eye is held in adduction). If unrestricted, this produces a sudden, saccadic movement with relatively high speed and sometimes large amplitude. If paralysis is present, movement may still occur (due to relaxation of the contracted antagonist), but it is slower, smaller (a centripetal abduction), and usually does not cross the midline (no centrifugal abduction). Note, however that large “spring-back” rotations under anesthesia, entirely passive and due to “extremely” stretched muscles, may reach peak velocities similar to normal voluntary saccades.

Severe restrictions as well as simultaneous paralysis of opposing muscles often cause inversion of deviations when fixation changes sides. For example, in horizontal insufficiency (restrictive or paralytic) of RE horizontal rotations, esotropia appears in dextroversion and exotropia in levoversion. With vertical limitations of the RE, L/R deviation appears in supraversion and R/L deviation in infraversion.

Once restriction is diagnosed, its localization may be studied by considering the restriction as a fixed “point” around which the eye “rotates” (effectively translating; Figure 17). The larger the lever arm (distance from restriction point to traction point) the greater the obtainable motion. The eye may be translated outward (toward the restriction side; Figure 17d, g) or inward (opposite the restriction; Figure 17c,h). A short or stiff antagonist (fibrotic or contracted) may act as the restricting force. In this case, outward translation is more limited than inward. Large scar tissues may abolish translational rotations entirely.

Measurements of the deviation in diagnostic positions(32)

As noted, slight dysfunctions are not readily detected by monocular rotations (ductions). Comparing binocular conjugate rotations (versions) reveals them as (binocular) deviations. Causes vary, but all present as defective rotations-whether from abnormal stimulation (insufficient or excessive) or restricted movement despite normal stimulation.

It is well established that muscle dysfunction manifests in all gaze directions but maximally in the diagnostic position of a specific muscle, that is, the direction where its primary action is most required. For example, the left lateral rectus (LLR) muscle, whose primary action is abduction, is maximally tested when the eye looks as far left as possible. While LLR underaction appears in all positions, the greatest esodeviation occurs in levoversion, especially when the left-eye fixates. This follows Hering's and Sherrington's laws (Figure 18). Since LLR stimulation decreases progressively from left to right, the minimal deviation occurs in dextroversion, particularly when the right eye fixates (Figure 18). Clinically, this explains compensatory head positions: in LLR paralysis, the head turns left. (Mnemonic: the paralyzed muscle “pulls” the head toward its side.)

Similarly, the right lateral rectus (RLR) muscle is maximally activated in abduction (right gaze). Here, the esodeviation is greatest when the right fixates (Figure 18). Conversely, the minimal deviation occurs when the eye moves to the left, with the fixation of the left eye.

In summary, for an esodeviation supposedly caused by an underaction of one or both LR muscles-whether due to paralysis, paresis, or mechanical restriction of abduction (as if the LR were “underactive”)-only two measurements are required to identify the affected muscle:

a) Looking to the right with fixation by the right eye (maximal deviation caused by an affected RLR; minimal deviation caused by an affected LLR);

b) Looking to the left with fixation by the left eye (maximal deviation caused by an affected LLR; minimal deviation caused by an affected RLR).

Thus, the RLR and LLR form a diagnostic pair in cases of esodeviation. Measuring their maximal actions allows differentiation of the primarily affected muscle. If measurements are approximately equal, both muscles should be considered similarly affected. Objectively, the limit of measurement error is considered 2A; therefore, a difference of about 5A between two measurements cannot reliably indicate incomitance or prove that one muscle is more underactive than the other. Because other sources of error exist, only differences greater than 10A should be considered reliable criteria for unequal measurements.

The rationale for this differential diagnostic test-comparing binocular deviations in opposite gaze directions and eye fixations-is that when one muscle is maximally activated, its counterpart is minimally activated, and vice versa. This principle of symmetry between opposed ocular positions is implicit. For example, one can compare the deviation at 40° right gaze with the right eye fixating to the deviation at 40° left gaze with the left-eye fixating (*12). If, however, the RLR is paralytic (or right-eye abduction is severely restricted), maximal abduction of the right eye may reach only 0° (absolute abduction failure). This alone is conclusive proof of severely limited ocular rotation. Nevertheless, testing the rotation of the left eye is still necessary. If the left eye parting from a position of greater adduction also fails to reach or exceed +20° of adduction (that is, no relative abduction is present/ this indicates an even more severe restriction of left eye abduction. In summary, symmetry of rotational amplitudes is advisable for testing comparative functions and eliciting the greatest deviations.

Overactions and underactions

Distinguishing muscular overaction from underaction is not straightforward. A muscular overaction (excessive rotation) of the LLR would produce an exodeviation, the exact opposite of the esodeviation caused by its underaction (reduced or absent action, or excessive resistance from opposing forces). However, when “excessive” or “insufficient” action refers to a different muscle-such as the direct antagonist (LMR) or the yoke muscle (RMR)-further considerations are needed. In practice, underactions and overactions usually occur together, one being the consequence of the other. Primary underactions (paralysis, scarring, or other mechanical restriction) are most frequent, but primary overactions may also occur. A typical example of primary overaction is that of the medial recti in accommodative esodeviation.

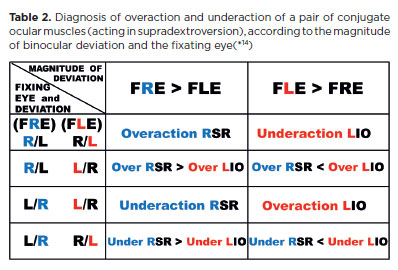

It is common to assume that if a muscle (e.g., the LLR) is “underactive,” its direct antagonist (LMR) is “overactive.” Thus, if an esotropia is greater in dextroversion when the fixation is directed by the right eye, the diagnosis is of a RLR underaction; but if the deviation is greater when the fixation is directed by the left eye, the diagnosis is of a LMR overactiion. However, when faulty rotation is caused by a mechanical restriction, true muscular dysfunction may not exist. Conversely, when yoke muscles (LLR and RMR) are tested simultaneously, a deviation arises if one action is greater and/or the other smaller. Frequently, a muscular underaction is accompanied (though not always) by overaction of the yoke muscle. For instance, in supradextroversion -when the actions of the RSR and L1O are tested-an L/R deviation may appear, whether the RE or LE is fixating. This may be interpreted either as an RSR underaction or an L1O overaction.

The difficulty arises in interpretation: 1f the RE is fixating and the LE (deviated eye) appears higher than the RE (L/R deviation), this is typically described as a LIO overaction. Technically, however, since the right eye controls fixation, the measurement reflects a RSR underaction. Conversely, if the LE is fixating and the RE is lower (non-fixating), this is often described as a RSR underaction, but in fact reflects relative “overactivity” of the LIO. Strictly, the diagnosis should be RSR underaction (with secondary L1O overaction) when the L/R deviation is greater during RE fixation. Conversely, the dominant condition should be described as LIO overaction if the deviation is greater during LE fixation. Other differential patterns may also occur (Table 2).

Note that although “underaction” refers to the muscle of the lower eye and “overaction” to the muscle of the higher eye, the determining factor for diagnosis is which eye’s fixation produces the greater deviation. For example, in left Brown's syndrome, a vertical R/L deviation is observed in supradextroversion (first row of Table 2). Parents often report that the RE “deviates” upward (apparent RSR overaction), whereas the true cause is underaction of the LIO (restricted left-eye rotation).

Most commonly, the same type of vertical imbalance (R/L or L/R) occurs in all gaze directions, but dissociated (or “divergent”) vertical deviations may also be observed(*13).

Diagnostic muscular pairs (maximal and minimal deviations)

As noted earlier, underaction of the RLR produces an esodeviation that is greater in dextroversion, when the right eye directs fixation (“Rr”). The less the RLR is required, the smaller the consequent deviation becomes. In the early stage of dysfunction, when the muscle is completely relaxed (at left gaze), no deviation may be present. Over time, however, “secondary” defects arise: overaction of the direct antagonist (RMR), overaction of the yoke muscle (LMR), and eventually underaction of the antagonist of the yoke (LLR). These factors increase deviations in their respective directions of maximal action and gradually decrease the differences between them. Until a fully “concomitant” (equal) deviation occurs in all gaze positions, the deviation remains smaller in levoversion, especially when the left eye directs fixation (“rL”).

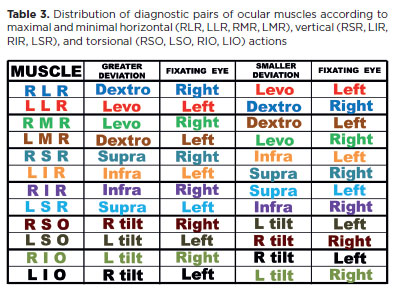

The opposite condition applies to the underaction of the LLR. By reversing “greater” and “smaller,” “dextroversion” and “right eye,” with “levoversion” and “left eye” (and vice versa), the logic holds (Table 3). Thus, an esodeviation caused by LLR underaction-whether primary or secondary-is greater in left gaze during fixation by the left eye (Ll), and smaller in right gaze during fixation by the right eye (lR).

In summary, in an esodviation (underactions of one, or both, the lateral recti muscles), deviation in dextroversion is due to a primary effect caused by the fixation of the right eye (RR) plus a secondary effect caused by a possible underaction of LLR (lR), that is, (Rr + lR). Deviation in levoversion is primarily due to an effect caused by the left eye fixation (LL) but, also, a secondary effect caused by a RLR underaction (rL), that is, (LL + rL). However, such a difference of deviations at right and left gaze, (RR + lR) - (LL + rL) equals to (RR - rL) - (LL - lR), that is, the difference between the maximal and minimal deviations caused by a possible RLR underaction (first term) and that of a possible LLR underaction (second term). Therefore, these muscles form the diagnostic pair for differentiating the cause of an esodeviation.

Similarly, the RMR and LMR constitute a diagnostic pair for exodeviation, the RSR and LIR for an L/R vertical deviation, and the LSR and RIR for an R/L deviation (Table 3). The oblique muscles, whose primary actions are torsional (frontal plane), should be evaluated by measuring cyclotorsional deviations. These torsions occur automatically, though not voluntarily, during head tilts to either side (right or left shoulder).

However, observations of cyclorotations are difficult because they cannot be voluntarily elicited and because reliable reference points for measurement are lacking. In addition, torsional deviations cannot be measured by the usual prism method employed for horizontal and vertical deviations. Only subjective reports of cyclodeviation are available, which is a major limitation in many participants. In summary, because the primary functions of the oblique muscles (cyclorotations) and their disturbances (torsional deviations) are not easily assessed clinically, alternative methods are required.

Fortunately, the vertical actions of the oblique muscles are also clinically relevant (hence their designation as cyclovertical muscles). A useful methodological circumstance allows differentiation between vertical recti and oblique actions: the vertical actions of the vertical recti are greater than those of the obliques in all positions of elevation or depression. However, vertical rectus action is relatively stronger in abduction, whereas oblique vertical action is stronger in adduction.

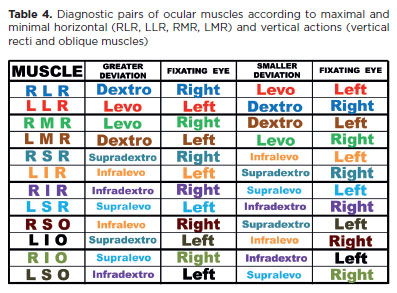

Therefore, in elevation combined with right gaze (supradextroversion: abduction and elevation of the right eye; adduction and elevation of the left eye), the RSR and L1O achieve their maximal vertical actions. These two muscles are considered yoke (or conjugate) muscles, although their functions and purposes differ. Importantly, their vertical actions cannot be matched directly. For the same reason, the pairs R1R-LSO, LSR-R1O, and L1R-RSO, though anatomically yokes, should not be considered diagnostic pairs because vertical actions of obliques and vertical recti are not comparable.

Accordingly, table 3 is replaced by table 4, which lists the clinical diagnostic positions for vertical recti and oblique muscles.

The gaze directions and fixations shown in table 4 are the classical “diagnostic positions” for each muscle. However, vertical recti and obliques cannot be com pared directly because of their different rotational properties. Instead, equivalences are considered only between diagonally opposite muscles (RSR-L1R, R1R-LSR, RSO-L1O, R1O-LSO).

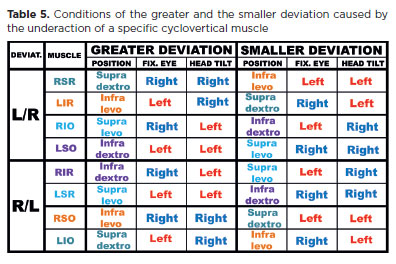

Testing the muscular diagnostic positions with head tilts

In cases of a vertical deviation (e.g., L/R deviation), measurements taken at the so-called muscular diagnostic positions are reliable when comparisons are limited to pairs of muscles with equivalent functions. For example, differentiation can be made between vertical recti (RSR and L1R) or between obliques (LSO and R1O). However, comparisons between nonequivalent muscles-such as RSR and LSO (or L1R and R1O), or RSR and R1O (or L1R and LSO)-introduce bias favoring the vertical recti. This occurs because, even in adduction, elevation produced by the RSR exceeds that of the R1O; similarly, depression produced by the L1R exceeds that of the LSO, even in adduction.

Therefore, in an L/R deviation, diagnostic certainty is obtained only when the deviation produced by a vertical rectus (RSR or L1R) is smaller than that produced by the corresponding oblique (R1O or LSO). Such conditions are paradigmatic: For example, elevation of the right eye being worse in adduction than in abduction is a hallmark of right Brown's syndrome. 1n these circumstances, no complementary duction test is required to confirm the diagnosis. 1f the RSR were weak, an L/R deviation would be greater in abduction of the right eye. On the contrary, even with complete removal of the R1O, the right eye would still elevate in adduction. Thus, the cause cannot be a paralytic R1O but rather a mechanical restriction preventing elevation, especially in adduction. A similar rationale applies to deficits of depression greater in adduction than abduction, as seen when the inferior oblique is excessively tight after resection and anterior transposition surgery intended to correct dissociated vertical deviation (DVD).

For this reason, it is preferable to associate head tilts with the test of diagnostic positions in vertical deviations. Head tilts not only require greater activation of vertical recti and obliques (through stimulation of their torsional functions), thereby exposing even subtle dysfunctions, but also introduce a compensatory mechanism favoring the obliques relative to the stronger vertical actions of the vertical recti musclus (Figure19).

In an R/L deviation, the potentially underactive muscles are RIR, RSO, LIO, and LSR (Figure 20). Tilting the head to the right evokes levocyclotorsion: incyclotorsion of the right eye (stimulating RSR and RSO) and excyclotorsion of the left eye (stimulating LIO and L1R). Thus, among the four suspect muscles, two (RSO and LIO) are stimulated with right head tilt (Figures 19 and 20, below left). The remaining two (R1R and LSR) are stimulated by tilting the head to the left (Figures 19 and 20, below right).

Accordingly, testing the diagnostic positions of the RSO (infralevoversion) and L1O (supralevoversion) with a right head tilt provides additional stimulation for both their vertical and torsional actions. Conversely, testing the diagnostic positions of the R1R and LSR with a left head tilt adds supplementary stimulation for their vertical and torsional roles.

In an L/R deviation the same logic applies (Figure 21). Here, the potentially underactive muscles are maximally stimulated by combining diagnostic positions with the appropriate head tilt, thereby increasing the likelihood of detecting dysfunction.

Two simple mnemonic rules help determine the appropriate head tilt to maximize stimulation in vertical deviations:

1. The normally inclined diagnostic positions of the potentially underactive muscles are shifted horizontally.

2. A head tilt that stimulates the obliques is directed toward the higher eye (e.g., to the right in an R/L deviation, Figure 20; to the left in an L/R deviation, Figure 21). Conversely, a head tilt that stimulates the vertical recti is directed toward the lower eye (to the left in an R/L deviation, Figure 20; to the right in an L/R deviation, Figure 21).

The criteria for comparing maximal deviation versus maximal variation

It should be noted that the strategy of adding a specific head tilt to increase the stress on the “diagnostic positions” of each of the four cyclovertical muscles possibly affected in a vertical deviation introduces a new diagnostic criterion. In the classical “diagnostic positions” (with the head erect), the position in which an affected muscle shows its maximal deviation (e.g., for the RSR, supradextroversion with the right eye fixating) coincides with the position in which its corresponding opponent muscle (the L1R) shows its minimal deviation (Table 4).