Cristian Cartes1,2; Claudia Zapata1; Camila Lopez1; Camila Gaete3; Nicolás Aguilera2; Christian Segovia4,5

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2025-0148

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: To evaluate the effects of a propylene glycol–hydroxypropyl guar nanoemulsion on symptoms and ocular surface parameters in patients with evaporative dry eye.

METHODS: This prospective, single-center, interventional study included patients aged 18–50 years with evaporative dry eye who received a propylene glycol–hydroxypropyl guar nanoemulsion. Participants were instructed to instill the nanoemulsion three times daily for 90 days. Evaluations included the Ocular Surface Disease Index, tear osmolarity, tear meniscus height, lipid layer thickness, noninvasive tear break-up time, fluorescein tear break-up time, corneal fluorescein staining (National Eye Institute Scale), Schirmer’s test I, and meibum quality.

RESULTS: Thirty-three participants were enrolled, and 30 completed the study. The mean age was 36 ± 10 yr, and 73.3% were women. The mean Ocular Surface Disease Index score significantly decreased from 43.1 ± 20 at baseline to 25.2 ± 17 at 3 months (p=0.009). Median corneal fluorescein staining decreased from 2 (IQ range=1–3) to 1 (IQ range 25–75 = 0–1) at the final follow-up (p=0.002). The mean fluorescein tear break-up time increased significantly increased from 3.8 ± 2.1 at baseline to 5.8 ± 2.2 at 3 months (p=0.002). Tear osmolarity decreased significantly (p=0.01) and lipid layer thickness improved markedly (p<0.001). No significant changes were observed in tear meniscus height or noninvasive tear break-up time (p>0.05).

CONCLUSIONS: Treatment with a propylene glycol–hydroxypropyl guar nanoemulsion significantly improved dry-eye symptoms, corneal staining, tear film stability, and lipid layer quality in patients with evaporative dry eye. No adverse events were reported, supporting the safety and efficacy of this formulation.

Keywords: Dry eye syndromes/drug therapy; Meibomian gand dysfunction/drug Dry Eye therapy; Tears; Emulsions; Lubricant eye drops; Nanoparticles; Propylene glycol/therapeutic use; Polysaccharides/ therapeutic use

INTRODUCTION

Dry-eye disease (DED) is a multifactorial condition that affects the ocular surface and accounts for a substantial number of consultations with eye care professionals(1). Patients with DED experience ocular discomfort and visual disturbances that can significantly impair daily functioning and overall quality of life(2).

Globally, DED affects 5%–50% of the population and is categorized into three main types: aqueous-deficient DED, characterized by reduced tear production; evaporative dry eye (EDE), associated with increased tear evaporation due to dysfunction of the tear film lipid layer; and mixed DED, which presents features of both types(3,4). EDE is the most prevalent subtype and is commonly linked to meibomian gland (MG) dysfunction (MGD)(5). The MGs play an essential role in maintaining tear film stability by reducing tear evaporation. When MG function is compromised, tear osmolarity increases, leading to ocular surface inflammation and epithelial damage(6).

Although MGD is present in approximately 70% of DED cases, modern lifestyles further exacerbate ocular surface stress through environmental exposure and prolonged visual display terminal (VDT) use(7–9). These factors contribute to accelerated tear evaporation due to low ambient humidity and a reduced blink rate associated with screen use(9,10). The interaction of MGD, environmental stressors, and extended screen time not only diminishes ocular comfort but also negatively impacts ocular surface health. This was particularly evident during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, when increased VDT use led to a higher prevalence of DED symptoms, even among younger individuals(11,12).

Because DED symptoms can impair visual performance, daily activities, and quality of life, the primary goal of treatment is to alleviate discomfort and restore ocular surface and tear film homeostasis without disrupting routine activities(13). Artificial tear substitutes remain the mainstay of DED therapy; however, there remains a need for formulations capable of targeting all layers of the tear film(4,13).

Most conventional eye drops focus on replenishing the aqueous layer of the eye. In contrast, a newer formulation— a nanoemulsion containing propylene glycol (PG) and hydroxypropyl guar (HPG)—offers a novel approach to tear film stabilization(14). The proposed mechanisms of the PG–HPG nanoemulsion involve synergistic actions: PG acts as a demulcent that enhances hydration and epithelial protection, while HPG forms a gel-like matrix that adheres to damaged epithelial cells, stabilizing the tear film by anchoring lipids and reducing evaporation(15). Phospholipid nanoparticles in the formulation further facilitate the uniform distribution of lipids across the tear film, thereby supporting its stability(15,16).

Previous studies have demonstrated that this nanoemulsion effectively reduces symptoms of DED in both general patients and contact lens wearers while improving tear film stability(4,17,18). However, most studies have evaluated short-term effects, typically lasting under 1 month, and have not reported significant improvements in the lipid layer of the tear film(1,4,14,17,18). Notably, a study with a 6-month follow-up reported a measurable enhancement in lipid layer thickness (LLT) beginning at the third month(19). These findings underscore the importance of extended follow-up to gain a deeper understanding of the long-term effects of treatment on the ocular surface.

The present study aimed to assess the efficacy of PG–HPG nanoemulsion, administered three times daily as the initial and sole treatment, in patients with EDE over a 3-month follow-up period.

METHODS

Study design

This prospective, single-center, interventional study was conducted in adult patients with EDE and was registered in the ISRCTN registry (10208997). Participant enrollment took place between September 2023 and March 2024. The study included a recruitment visit (Days −7 to 0) to determine eligibility, during which participants completed the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire and underwent a clinical interview to identify symptoms suggestive of DED. Eligible participants were assessed on Days 1 and 2 as part of the recruitment process, during which ocular surface parameters were evaluated to confirm symptomatic EDE. Participants who met all inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Follow-up visits were conducted at Day 30 (visit 1) and Days 90–91 (visit 2) to assess and record dry-eye symptoms and ocular surface parameters.

Eligibility criteria

Participants were adults aged 18–50 years with symptomatic EDE, as defined according to the Dry Eye Workshop II (DEWS II) criteria(20). Inclusion criteria included an OSDI score ≥13, at least one clinical sign (fluorescein tear break-up time [FTBUT] <10 s, tear osmolarity ≥308 mOsm/L, inter-eye difference ≥8 mOsm/L, or positive corneal staining), and evidence of MGD with a secretion score >4(20,21). Exclusion criteria were as follows: contact lens use, previous ocular surgery, major systemic or ocular diseases, active ocular inflammation or autoimmune conditions (e.g., ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, and Sjögren’s syndrome), use of glaucoma medications or other topical eye drops, and Schirmer’s test results <10 mm. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study protocol was approved by the Centro de la Vision Ethics Committee and adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Assessment

The collected data included age, sex, and relevant medical and ophthalmic histories. All participants underwent a standardized ocular surface evaluation protocol, which included OSDI questionnaire, using the validated Spanish version culturally adapted to the study population(22); tear osmolarity (TearLab Corporation, San Diego, California); average noninvasive tear breakup time (ni-TBUT); tear meniscus height (TMH); LLT, subjectively classified by a blinded and experienced examiner into four categories – normal, mild, moderate, and severe – using a standardized grading scale (Keratograph 5M; Oculus, Germany)(23); FTBUT; corneal fluorescein staining, graded using the National Eye Institute Scale(24); Schirmer’s test I; and MG secretion evaluation.

Meibomian gland secretion was assessed in the central eight glands of the lower eyelid. Each gland was graded on a 0–3 scale according to meibum quality: 0 = clear fluid, 1 = cloudy fluid, 2 = cloudy fluid with particulate matter, and 3 = thick, toothpaste-like secretion. The total secretion score was calculated by summing the scores of all examined glands(25). All tests were conducted in a fixed sequence, as outlined in Appendix A.

Following recruitment, participants were instructed to instill PG–HPG nanoemulsion (Systane Complete; Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas) three times daily for the duration of the study. They were advised to refrain from using any eye drops on the day of ocular surface assessment. No additional lifestyle recommendations or restrictions were provided.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

The primary outcome was symptom improvement, as measured by the OSDI. Based on pilot data showing a standard deviation (SD) of 22, a sample size of 25 participants was estimated to detect a 15-point difference between baseline and final visits, with 90% power and a two-sided α of 0.05.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics. For inferential analyses, only the right eye of each participant was included to avoid intra-subject correlation. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and parametric or nonparametric tests were applied as appropriate. To complement mean change analyses, the minimal clinically significant difference (MCID) for the OSDI was also considered. Based on prior studies, a ≥ seven-point reduction was defined as the threshold for clinically meaningful improvement(26). The proportion of participants achieving this threshold at the 3-month follow-up was calculated and reported as an indicator of individual-level treatment response. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

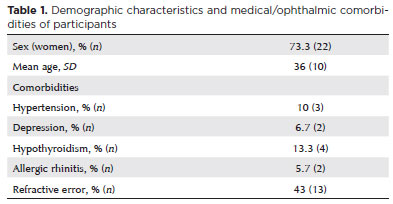

A total of 33 participants were assessed for eligibility, and 30 completed the study, were included in the final analysis, and were deemed eligible for inclusion. The mean age was 36 ± 10 years (range, 18–50 years), and 22 participants (73.3%) were female. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, including ophthalmic and general comorbidities, are summarized in table 1.

Dry-eye symptom scores

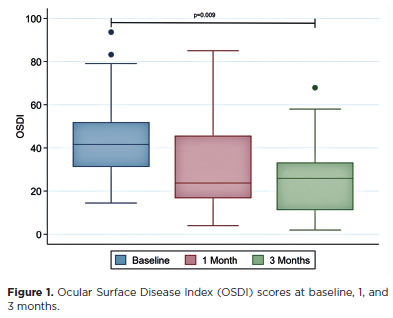

DED symptom scores improved progressively throughout the follow-up period. The mean OSDI scores were 43.1 ± 20 at baseline, 31.4 ± 24 at 1 month, and 25.2 ± 17 at 3 months (p=0.009; Figure 1). Moreover, 56.7% of participants achieved the MCID, defined as a reduction of 7 points or more in the OSDI score, at Month 3.

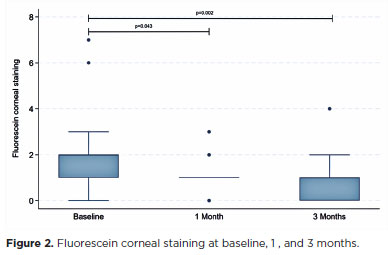

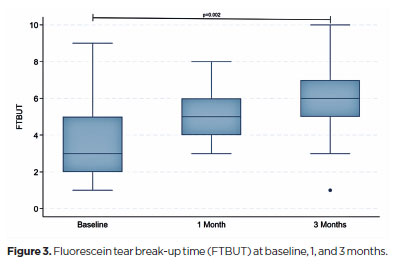

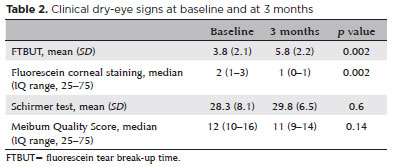

Clinical dry-eye signse

Fluorescein corneal staining scores improved significantly, decreasing from a median of 2 (interquartile range [IQR]=1–3) at baseline to 1 (IQR=0–1) at the final visit (p=0.002; Figure 2). The FTBUT also increased significantly, from 3.8 ± 2.1 at baseline to 5.8 ± 2.2 at the final follow-up (p=0.002; Figure 3). No significant changes were observed in Schirmer’s test results or meibum quality scores during the study period (Table 2).

Noninvasive dry-eye tests

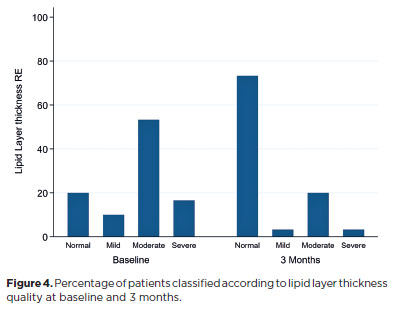

The mean tear osmolarity decreased significantly from 301 ± 8.5 mOsm/L at baseline to 296 ± 6.4 mOsm/L at the final visit (p=0.01). No significant difference was observed in TMH between the initial and final visits (0.25 ± 0.1 vs 0.24 ± 0.1, p=0.6). The mean ni-TBUT showed a trend toward improvement (11.3 ± 4.7 vs 14.2 ± 5.5, p=0.05). LLT quality improved significantly between baseline and the final visit (p<0.001; Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a nanoemulsion-based lubricant eye drop containing PG and HPG in relieving symptoms of DED and improving ocular surface parameters in patients with EDE over 3 months.

The findings demonstrated significant improvements in both subjective symptoms and objective clinical signs of DED, with symptom relief evident after 1 month of treatment and continued improvement through 3 months. These results are consistent with prior studies by Yeu et al.(1) and Silverstein et al.(4), who reported rapid and sustained symptom relief with PG–HPG nanoemulsion eye drops across different DED subtypes. Similarly, Pucker et al.(17) found that PG–HPG nanoemulsion effectively alleviated contact lens-related discomfort after 2 weeks of treatment. Craig et al.(19) reported that symptom improvement plateaued after the first month and persisted for 6 months. In contrast, the current study demonstrated continued improvement up to three months, possibly because our cohort included patients with initially reduced LLT. This group appears exceptionally responsive to lipid-containing lubricants(19,27).

Improvements in tear film stability and ocular surface integrity were observed after the first month of treatment. Previous studies have shown an increase in TBUT with lipid-based and nonlipid artificial tears (18,28). However, lipid-containing formulations appear to confer longer TBUT, especially after exposure to environmental stress(18). These findings support the use of lipid-based eye drops for managing EDE, particularly in younger populations that are frequently exposed to environmental stress and prolonged use of VDTs(12).

Corneal fluorescein staining showed consistent improvement from the first month of treatment, in agreement with multicenter studies by Yue et al.(1) and Nishiwaki-Dantas et al.(14). Craig et al.(19) also observed gradual improvements in ni-TBUT and corneal staining, which became evident only after 3 months of consistent use. These findings suggest that sustained ocular surface recovery requires prolonged tear film supplementation(19,29).

LLT showed significant improvement after 3 months of using PG–HPG nanoemulsion, corroborating the findings of Craig et al.(19), who reported a similar enhancement in LLT from day 90 onward. The underlying mechanism remains uncertain, but the improvement is unlikely to be solely attributable to transient lipid supplementation. A comparative study between PG–HPG nanoemulsion and an aqueous-based tear substitute demonstrated an increase in LLT 15 min after instillation. However, this effect was not sustained at 1 h or 1 month, and no long-term follow-up was performed(27). Likewise, Muntz et al.(18) reported short-term LLT enhancement following PG–HPG nanoemulsion use, but the assessment was limited to the immediate postinstillation period. The delayed yet sustained LLT improvement observed here suggests that regular use may promote long-term tear film stabilization, potentially through reduced inflammation and improved MG function(5,19). This supports the continuous use of lipid-based lubricants, rather than intermittent application, to restore ocular surface homeostasis(19,27–30).

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size may have reduced the statistical power to detect significant differences in ni-TBUT, despite an observable improvement trend. Additionally, the single-arm design precludes direct comparison with a control group. Nonetheless, as a preliminary investigation, the study effectively demonstrated the potential efficacy of the PG–HPG nanoemulsion, showing significant and consistent improvements in both symptoms and clinical parameters, including LLT.

The study population, aged 18–50 year, may not represent the broader DED population, which often includes older individuals. This criterion was selected to minimize confounding by age-related ocular surface changes and polypharmacy, but it limits generalizability. Similarly, the single-center design may restrict external validity. Future multicenter trials involving more diverse populations would strengthen these findings.

Notably, the three-month follow-up – longer than in most comparable studies – provides valuable insight into the sustained effects of the nanoemulsion. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second study to date suggesting a potential benefit of this formulation on LLT.

In conclusion, PG–HPG nanoemulsion eye drops were effective in improving both subjective symptoms and objective clinical signs of DED, including OSDI scores, corneal staining, FTBUT, and LLT in patients with EDE over 3 months. The formulation was well tolerated, with no severe adverse events reported.

The delayed improvement in LLT observed in this study suggests a potential long-term effect of the lipidbased formulation. Although the precise mechanism remains to be elucidated, it may involve progressive enhancement of MG function and restoration of ocular surface homeostasis. Further studies incorporating detailed anatomical assessments of the MGs and extended follow-up are warranted to confirm these findings and clarify the underlying mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by Alcon Laboratories (Grant 73577869).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS:

Significant contribution to conception and design: Claudia Zapata, Cristián Cartes. Data Acquisition: Christian Segovia, Camila López. Data Analysis and Interpretation: Christian Segovia, Cristián Cartes, Claudia Zapata. Manuscript Drafting: Camila Gaete, Nicolás Aguilera. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Cristián Cartes, Claudia Zapata, Camila Gaete. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Cristian Cartes, Claudia Zapata, Camila Lopez, Camila Gaete, Nicolás Aguilera, Christian Segovia. Statistical analysis: Christian Segovia. Obtaining funding: Cristián Cartes. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Camila López, Nicolás Aguilera, Camila Gaete. Research group leader: Cristián Cartes.

REFERENCES

1. Yeu E, Silverstein S, Guillon M, Schulze MM, Galarreta D, Srinivasan S, et al. Efficacy and safety of phospholipid nanoemulsion-based ocular lubricant for the management of various subtypes of dry eye disease: A phase iv, multicenter trial. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:2561-70.

2. Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276-83.

3. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop. Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):75-92.

4. Silverstein S, Yeu E, Tauber J, Guillon M, Jones L, Galarreta D, et al. Symptom relief following a single dose of propylene glycol-hydroxypropyl guar nanoemulsion in patients with dry eye disease: A phase IV, multicenter trial. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:3167-77.

5. Schaumberg DA, Nichols JJ, Papas EB, Tong L, Uchino M, Nichols KK. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on the epidemiology of, and associated risk factors for, MGD. Investive Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):1994-2005.

6. Fogt JS, Kowalski MJ, King-Smith PE, Epitropolous AT, Hendershot AJ, Lembach C, et al. Tear lipid layer thickness with eye drops in meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016:10:2237-43.

7. Kamøy B, Magno M, Nøland ST, Moe MC, Petrovski G, Vehof J, et al. Video display terminal use and dry eye: preventive measures and future perspectives. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022;100(7)723-9.

8. Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, Jalbert I, Lekhanont K, Malet F, et al. TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):334-65.

9. Chlasta-Twardzik E, Górecka-Nitoń A, Nowińska A, Wylęgała E. The influence of work environment factors on the ocular surface in a one-year follow-up prospective clinical study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(3):392.

10. Alves M, Asbell P, Dogru M, Giannaccare G, Grau A, Gregory D, et al. TFOS Lifestyle Report: Impact of environmental conditions on the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2023;29:1-52.

11. Neti N, Prabhasawat P, Chirapapaisan C, Ngowyutagon P. Provocation of dry eye disease symptoms during COVID-19 lockdown. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):24434.

12. Cartes C, Segovia C, Salinas-Toro D, Goya C, Alonso MJ, Lopez-Solis R, et al. Dry eye and visual display terminal-related symptoms among university students during the coronavirus disease pandemic. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2022;29(3):245-51.

13. Pucker AD, Ng SM, Nichols JJ. Over the counter (OTC) artificial tear drops for dry eye syndrome. Vol. 2016, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2(2):CD009729.

14. Nishiwaki-Dantas MC, de Freitas D, Fornazari D, dos Santos MS, Wakamatsu TH, Barquilha CN, et al. Phospholipid nanoemulsion-based ocular lubricant for the treatment of dry eye subtypes: a multicenter and prospective study. Ophthalmol Ther. 2024;13(12):3203-13.

15. Rangarajan R, Ketelson H. Preclinical evaluation of a new hydroxypropyl- guar phospholipid nanoemulsion-based artificial tear formulation in models of corneal epithelium. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2019;35(1):32-7.

16. Garofalo R, Kunnen C, Rangarajan R, Manoj V, Ketelson H. Relieving the symptoms of dry eye disease: update on lubricating eye drops containing mhydroxypropyl-guar. Clin Exp Optom. 2021;104(8):826-34. Erratum in: Clin Exp Optom. 2022;105(1):101.

17. Pucker AD, McGwin G Jr, Franklin QX, Nattis A, Lievens C. Evaluation of systane complete for the treatment of contact lens discomfort. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020;43(5):441-7.

18. Muntz A, Marasini S, Wang MT, Craig JP. Prophylactic action of lipid and non-lipid tear supplements in adverse environmental conditions: a randomised crossover trial. Ocul Surf. 2020;18(4): 920-5.

19. Craig JP, Muntz A, Wang MT, Luensmann D, Tan J, Trave Huarte S, et al. Developing evidence-based guidance for the treatment of dry eye disease with artificial tear supplements: A six-month multicentre, double-masked randomised controlled trial. Ocul Surf. 2021;20:62-9.

20. Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, Djalilian A, Dogru M, Dumbleton K, et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):539-74.

21. Tomlinson A, Bron AJ, Korb DR, Amano S, Paugh JR, Pearce EI, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Report of the diagnosis subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):2006-49.

22. Traipe L, Gauro F, Goya MC, Cartes C, López D, Salinas D, et al. [Validation of the Ocular Surface Disease Index Questionnaire for Chilean patients]. Rev Med Chile 2020;148(2):187-95. Spanish.

23. Di Cello L, Pellegrini M, Vagge A, Borselli M, Desideri LF, Scorcia V, et al. Advances in the noninvasive diagnosis of dry eye disease. Appl Sci. 2021;11(21):10384.

24. Sall K, Foulks GN, Pucker AD, Ice KL, Zink RC, Magrath G. Validation of a modified National Eye Institute grading scale for corneal fluorescein staining. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:757-67.

25. Nelson JD, Shimazaki J, Benitez-del-Castillo JM, Craig JP, McCulley JP, Den S, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):1930-7.

26. Miller KL, Walt JG, Mink DR, Satram-Hoang S, Wilson SE, Perry HD, et al. Minimal clinically important difference for the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(1):94-101.

27. Weisenberger K, Fogt N, Swingle Fogt J. Comparison of nanoemulsion and non-emollient artificial tears on tear lipid layer thickness and symptoms. J Optom. 2021;14(1):20-7.

28. Srinivasan S, Williams R. Propylene glycol and hydroxypropyl guar nanoemulsion-safe and effective lubricant eye drops in the management of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022;16:3311-26.

29. Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, Benitez-del-Castillo JM, Dana R, Deng SX, et al. TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):575-628.

30. Baudouin C, Messmer EM, Aragona P, Geerling G, Akova YA, Benítez-Del-Castillo J, et al. Revisiting the vicious circle of dry eye disease: a focus on the pathophysiology of meibomian gland dysfunction. Brit J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(3):300-6.

Submitted for publication:

May 13, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

October 8, 2025.

Approved by the following research ethics committee: Centro de la Visión (ISRCTN registry 10208997).

Research Availability Statement:

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (CC) upon reasonable request.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior Associate Editor: Richard Y. Hida

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: CC is a speaker for Alcon, Sophia, and Thea. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.