Andrú Leite1,2; Rosana Pires da Cunha1,2

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2025-0071

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: This study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of strabismus surgical correction in patients with Down syndrome.

METHODS: We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients with Down syndrome who underwent strabismus surgery between January 1997 and May 2024 at an Ophthalmology Outpatient Clinic in São Paulo, Brazil. The data collected included age, sex, medical and ocular history, surgical details, and follow-up outcomes. The patients were categorized by strabismus type into esotropia, fourth nerve palsy, and mixed groups. Surgical success was defined as final alignment within 10Δ of orthotropia and, where applicable, whether there was resolution of abnormal head posture of ocular origin. Patients with postoperative follow-up <6 months were excluded.

RESULTS: A total of 37 patients (21 females) were included. Of these, 22 (59.5%) were in the esotropia group, 10 (27.0%) in the fourth nerve palsy group, and 5 (13.5%) in the mixed group. The surgical success rate in the esotropia group was 86.4%, with a mean preoperative deviation of 35.2 (± 6.5)Δ, and mean surgical correction of 30.1 (± 10.4)Δ. The success rate in the fourth nerve palsy group was 40.0%, with a mean preoperative deviation of 10.4 (± 4.3)Δ. Overall, success was achieved with a single surgical procedure in 73.0% of the sample. No significant associations were found between surgical success and the clinical and demographic variables, including sex, age at surgery, oblique muscle overaction, pattern strabismus, visual acuity, amblyopia, preoperative deviation, or postoperative follow-up duration (p>0.05).

CONCLUSIONS: When standard surgical tables are applied, strabismus surgery in patients with Down syndrome appears to be safe and effective. We found high success rates, particularly among patients with esotropia. We observed no tendencies toward over- or under-correction. These findings support the use of conventional surgical protocols with this patient population.

Keywords: Down Syndrome/complications; Strabismus/surgery; Esotropia/surgery; Oculomotor nerve diseases/physiopathology; Vision disorders; Humans; Brazil.

INTRODUCTION

Down syndrome (DS) is among the most common genetic disorders, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 691 live births(1). Children with DS commonly present with multiple systemic and developmental abnormalities. These can include congenital heart defects, gastrointestinal malformations, hypothyroidism, celiac disease, and varying degrees of neuropsychomotor delay(1-3).

The development of the visual and oculomotor systems in individuals with DS differs substantially from that in the general population(4). Ophthalmological disorders are particularly common and can include refractive errors, palpebral fissure abnormalities, iris anomalies, and ocular misalignment. Strabismus is also a common ocular manifestation of DS, with a reported incidence ranging from 19-42%(5-11). This is significantly higher than the 1-5% incidence in the general population(12,13). A Brazilian study of 152 children with DS found a strabismus rate of 38%, with most cases being acquired esotropia(6).

Strabismus can significantly affect both visual function and quality of life, particularly in children with developmental delays(14). While surgical correction is generally well tolerated and effective, the outcomes can be somewhat less predictable in this population(4).

This study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of strabismus surgery in patients with DS treated at an ophthalmology outpatient clinic in São Paulo, Brazil.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients with DS seen at the ophthalmology outpatient clinic Novo Olhar-Fundação Dr. Marcelo Cunha and the Associação de Pais e Amigos dos Excepcionais in São Paulo, Brazil, between January 1997 and May 2024. We collected clinical and demographic data, including age, sex, diagnosis, medical history, family medical history, ocular history, ophthalmic examination results, treatments performed (including surgeries), postoperative follow-up durations, and outcomes. The study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later revisions. It was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Associação de Pais e Amigos dos Excepcionais (approval no. 5.721.152).

The inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of DS, a diagnosis of strabismus, strabismus surgery, and a postoperative follow-up duration of at least 6 months. Patients without a diagnosis of DS, who did not undergo strabismus surgery, or whose postoperative follow-up was <6 months, were excluded. Both children and adults with DS were included in our sample. Ocular alignment was assessed using the alternate prism cover test or, in patients with poor fixation or collaboration in both primary and cardinal gaze positions, the Krimsky test. All motor evaluations were conducted with corrected visual acuity when necessary. The patients were classified into three groups based on strabismus type: esotropia, fourth nerve palsy, and mixed. The mixed group comprised patients with intermittent exotropia, sixth nerve palsy, and monocular elevation deficiency. Esotropia was categorized as infantile if it began before 6 months of age or acquired if it developed after 6 months. Fourth nerve palsy was diagnosed using the Parks-Bielschowsky three-step test(15).

All of the participants with esotropia underwent bilateral medial rectus recession based on standard surgical tables(16). The surgical plan for those in the fourth nerve palsy group followed the guidelines proposed by Souza-Dias(17). The surgeries were performed by several different surgeons on our team.

The extent of surgical correction was assessed by comparing each patient's preoperative deviation with their final postoperative alignment. For patients with esotropia, the surgical dose-response was calculated by dividing the surgical correction by the sum in millimeters (mm) of the correction in both eyes. Surgical success was defined as final alignment within 10 prism diopters (Δ) of orthotropia. Where applicable, surgical success also included resolution of any abnormal head posture of ocular origin.

Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages, and continuous data as means and standard deviations (range). Statistical tests were performed using R1 or SPSS for Windows, v. 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed alpha of 0.05 (p-value) and a 95% confidence interval. The relationships between quantitative and qualitative variables were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U-test or the Wilcoxon test for two variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for three or more variables.

RESULTS

A total of 37 patients (21 female) met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 22 (59.5%) were in the esotropia group, 10 (27.0%) were in the fourth nerve palsy group, and 5 (13.5%) were in the mixed group.

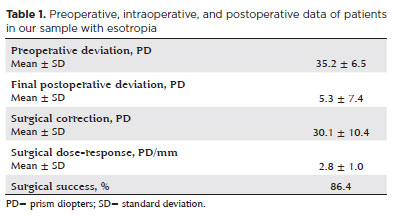

Of the 22 patients (14 female) with esotropia, 10 (45.5%) had infantile esotropia and 12 (54.5%) had acquired esotropia. The mean age at surgery was 8.3 (± 6.0) (2.3-30.4) years. Ten (45.5%) patients had pattern strabismus (seven A-pattern and three V-pattern), and 5 (22.7%) had oblique muscle overaction. The mean spherical equivalent (SE) was 1.6 (± 3.8) (−6.3-6.4) diopters (SE) in the right eye, and 1.6 (± 3.9) (−7.3-7.3) diopters in the left eye. The mean visual acuity was 0.3 (± 0.3) (0-1.1) logMAR in the right eye, and 0.4 (± 0.3) (0-1) logMAR in the left eye. The mean preoperative deviation in the esotropia group was 35.2 (± 6.5) (25-50)Δ. The mean surgical correction was 30.1 (± 10.4) (0-50)Δ, and the mean surgical dose-response was 2.8 (± 1.0) (0-4.2)Δ/ mm. The mean postoperative deviation was 5.3 (± 7.4) (0-30)Δ. The mean postoperative follow-up duration was 6.8 (± 6.1) (0.5-22.0) years. We achieved surgical success in 19 (86.4%) patients. The remaining three (13.6%) had residual esotropia. There were no instances of overcorrection in the esotropia group. Table 1 presents preoperative, surgical, and postoperative data for the esotropia group.

Among the 10 participants (six male) in the fourth nerve palsy group, the mean age at which strabismus was diagnosed was 12.0 (± 10.1) (4.0-24.0) months, and the mean age at surgery was 5.6 (± 4.8) (1.1-16.7) years. All of the fourth nerve palsy patients had overaction of one inferior oblique muscle, and none had pattern strabismus. The mean SEs were 0.5 (± 3.9) (−9.5-4.5) diopters in the right eye, and −0.2 (± 4.3) (−11.0-4.8) diopters in the left eye. The mean visual acuity was 0.6 (± 0.2) (0.3-0.8) logMAR in the right eye, and 0.6 (± 0.1) (0.5-0.9) logMAR in the left eye. The mean preoperative vertical deviation was 10.4 (± 4.3) (3.0-15.0)Δ. All of the participants in the fourth nerve palsy group had an abnormal head position of ocular origin. The mean postoperative follow-up duration was 5.7 (± 4.8) (0.6-17.3) years. At the final postoperative visit, 4 (40.0%) of the 10 had deviations <10Δ with resolution of the abnormal head position. Three of the patients developed esotropia postoperatively, and two suffered an increase in preexisting esotropia.

Of the six patients with unsuccessful surgical outcomes for the correction of fourth nerve palsy, three underwent a second procedure and achieved deviations <10Δ with resolution of the abnormal head position. One of these was lost to postoperative follow-up, while the other two remain under observation. Table 2 presents the preoperative, surgical, and postoperative data of the fourth nerve palsy group.

In the mixed group, three patients had intermittent exotropia, one had sixth nerve paresis, and one had monocular elevation deficiency. Among these, only the participant with monocular elevation deficiency did not achieve satisfactory surgical outcomes. This patient subsequently underwent a second procedure, which resulted in improved ocular alignment. Table 3 presents the data of the mixed group.

Overall, 73.0% of the patients in our sample achieved surgical success with one procedure. No significant association was found between the surgical group and success (p>0.05). Similarly, no significant differences in surgical success were found based on sex, age at surgery, diagnosis, oblique muscle overaction, the presence of pattern strabismus, visual acuity, amblyopia, SE, preoperative deviation, or postoperative follow-up duration.

DISCUSSION

Strabismus is a common disorder in patients with DS, yet there have been relatively few studies on the surgical correction of strabismus in this population. Our study provides insights into the surgical outcomes of strabismus treatment in patients with DS.

Although ocular misalignment is prevalent in children with developmental delays, the potential for binocular fusion can be preserved. This has important implications for the visual function and overall quality of life of such children(14). Previous reports suggest that the surgical outcomes of strabismus correction in patients with developmental delays can be somewhat unpredictable. With adjusted surgical doses, success rates ranging from 37.5% to 86.0% have been reported(18). In the present study, successful outcomes were achieved in the majority of patients (73.0%) using standard surgical tables. In those with esotropia, the success rate was 86.4%. Other studies of esotropia correction surgery in patients with DS have also demonstrated good results using standard values. Like us, these studies also found no significant tendencies toward over- or under-correction(5,10,19-22). Hiles et al.(5) reported satisfactory postoperative alignment (within 12Δ of orthotropia) in 10 DS patients with esotropia using the standard surgical dosages applied to typically developing children. An evaluation of 21 patients with DS and esotropia by Ruttum et al.(19) reported that 14 achieved postoperative alignment within 10Δ of orthotropia, five had residual deviations between 11 and 20Δ, and two had residual deviations >20Δ after a mean follow-up of 39 months. Yahalom et al.(10) retrospectively analyzed 15 children with DS and esotropia. Alignment within 10Δ was achieved in 85.7% of these following standard surgical protocols, with no trend toward overcorrection. Similarly, a study that compared 17 patients with DS and 27 controls undergoing surgery for esotropia reported comparable surgical success rates (76% in the DS group vs. 78% in the control group). This further supports the efficacy of standard surgical techniques in patients with DS(21). Another case-control study of bilateral medial rectus recession for esotropia compared 21 patients with DS and 42 age-matched controls. There were no significant differences between the two groups in either preoperative deviations or surgical outcomes, with success rates of 80.9% and 83.3%, respectively(22).

In the present study, the surgical dose-response for medial rectus recessions was 2.8Δ/mm. In a study by Motley et al.(20), it was 4.4Δ/mm. These values are comparable to those given by standard surgical dose tables, as well as values obtained in studies of children without developmental delays(16,23,24). Table 4 summarizes current research on the surgical correction of esotropia in patients with DS(5,10,19-22).

A non-surgical approach to the management of esotropia is botulinum toxin injection. A multicenter retrospective study of 53 patients with DS and esotropia (23 treated with conventional surgery and 30 with botulinum toxin injection) found a median preoperative angle of deviation of 30.0Δ in the surgery group and 37.5Δ in the botulinum toxin injection group, with no significant difference between the two. Conventional surgery resulted in a significantly higher success rate (65%) than botulinum toxin injection (30%) (p=0.011)(25).

Although a previous study has reported a correlation between hyperopia and esotropia in patients with DS(7), we found no relationship between refractive errors and surgical outcomes following esotropia correction.

There are a variety of possible contributors to abnormal head position in patients with DS, including skeletal, muscular, neurological, and otolaryngologic issues, and problems with the extraocular muscles. In a retrospective study of 259 patients with DS, abnormal head position was observed in 24.7%. Incomitant strabismus was found to be the most common cause, followed by nystagmus(26). Other factors that have been found to contribute to abnormal head position include macroglossia, atlantoaxial instability, and cervical muscle contracture(27). All of these are common in patients with fourth nerve palsy. When these factors are present, they can prevent complete resolution of abnormal head position following strabismus surgery. Among patients with DS and abnormal head positions, the underlying cause is unidentified in approximately 19%(26). In our study, four (40%) of the patients in the fourth nerve palsy group had deviations <10Δ and resolution of their abnormal head position at the final postoperative visit, with no further surgery required. Two (20%) had deviations <10Δ without abnormal head position resolution. One of these two had no vertical deviation, possibly due to cervical muscle contracture, while the other showed improvement in their abnormal head position after a second surgical procedure.

After the first surgery, half of the patients in the fourth nerve palsy group developed an increase in convergent deviation (three developed postoperative esotropia, and two exhibited an increase in preexisting esotropia). Additionally, one experienced vertical deviation reversal and was diagnosed with masked bilateral fourth nerve palsy. This underscores the importance of informing caregivers about the potential need for a second surgical intervention. Notably, we found no other studies that specifically address fourth nerve palsy surgery in patients with DS.

Divergent strabismus is much less common than other strabismus types in patients with DS, with an incidence of just 1%(6). In the mixed group, the three patients with intermittent exotropia all achieved surgical success (two who underwent bilateral lateral rectus recession, and one who underwent recession-resection), using standard surgical protocols. Similar results have previously been reported in three patients with DS who attained successful surgical outcomes for exotropia(5). Two of these patients underwent bilateral lateral rectus recession, while one underwent recession-resection. All achieved alignment within 10Δ of orthotropia using standard techniques.

Our study had some limitations. Its retrospective design and small sample size will have limited the statistical power of the analysis. Additionally, many of the patients in our study were treated within the public healthcare system, where access to surgery is more limited and delays in treatment are common due to comorbidities. This may also explain the higher age at surgery in our cohort compared with those in other studies, and could potentially have affected the results and success rates.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the outcomes of strabismus surgery in patients with DS. Strabismus can significantly affect visual development and quality of life(14). Therefore, its treatment is important to the development and vision of these patients. Our findings support the safety and effectiveness of strabismus surgery in this population using standard values, and demonstrate that there is no surgical tendency toward either over- or under-correction.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Significant contribution to conception and design: Rosana Nogueira Pires da Cunha, Andrú Leite da Silva. Data acquisition: Rosana Nogueira Pires da Cunha, Andrú Leite da Silva. Data analysis and interpretation: Rosana Nogueira Pires da Cunha, Andrú Leite da Silva. Manuscript drafting: Rosana Nogueira Pires da Cunha, Andrú Leite da Silva. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Rosana Nogueira Pires da Cunha, Andrú Leite da Silva. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Rosana Nogueira Pires da Cunha, Andrú Leite da Silva. Statistical analysis: Rosana Nogueira Pires da Cunha, Andrú Leite da Silva. Obtaining funding: not applicable. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Rosana Nogueira Pires da Cunha, Andrú Leite da Silva. Research group leadership: Rosana Nogueira Pires da Cunha.

REFERENCES

1. Hobson-Rohrer WL, Samson-Fang L. Down_syndrome. Pediatr Rev. 2013;34(12):573-4; discussion 574.

2. Van Gameren-Oosterom HB, Fekkes M, Buitendijk SE, Mohangoo AD, Bruil J, Van Wouwe JP. Development, problem behavior, and quality of life in a population based sample of eight-year-old children with Down syndrome. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21879.

3. Sherman SL, Allen EG, Bean LH, Freeman SB. Epidemiology of Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(3):221-7.

4. Watt T, Robertson K, Jacobs RJ. Refractive error, binocular vision and accommodation of children with Down syndrome. Clin Exp Optom. 2015;98(1):3-11.

5. Hiles DA, Hoyme SH, McFarlane F. Down's syndrome and strabismus. Am Orthopt J. 1974;24(1):63-8.

6. da Cunha RP, Moreira JB. Ocular findings in Down's syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122(2):236-44.

7. Haugen OH, Høvding G. Strabismus and binocular function in children with Down syndrome. A population-based, longitudinal study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2001;79(2):133-9.

8. Cregg M, Woodhouse JM, Stewart RE, Pakeman VH, Bromham NR, Gunter HL, et al. Development of refractive error and strabismus in children with Down syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(3):1023-30.

9. Yurdakul NS, Ugurlu S, Maden A. Strabismus in Down syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2006;43(1):27-30.

10. Yahalom C, Mechoulam H, Cohen E, Anteby I. Strabismus surgery outcome among children and young adults with Down syndrome. J AAPOS. 2010;14(2):117-9.

11. Ljubic A, Trajkovski V, Stankovic B. Strabismus, refractive errors and nystagmus in children and young adults with Down syndrome. Ophthalmic Genet. 2011;32(4):204-11.

12. Von Noorden GK, Campos EC. Binocular vision and ocular motility: theory and management of strabismus. 6a ed. New York: Mosby; 2002.

13. Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, Giordano L, Ibironke J, Hawse P, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in white and African American children aged 6 through 71 months the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11):2128-34.e1-2.

14. Liu G, Ranka MP. Strabismus surgery for children with developmental delay. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(5):417-23.

15. Bielschowsky A. Lectures on motor anomalies of the eyes: II. Paralysis of individual eye muscles. Arch Ophthalmol. 1935;13(1):33-59.

16. Wright KW, Farzavandi S, Thompson L. Colour atlas of ophthalmic surgery. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1991.

17. Souza-Dias C. Planejamento cirúrgico para as paresias unilaterais do oblíquo superior. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 1991;54(3):127-34.

18. Harrison A, Allen L, O'Connor A. Strabismus surgery for esotropia, Down Syndrome and developmental delay; is an altered surgical dose required? A literature review. Br Ir Orthopt J. 2020;16(1):4-12.

19. Ruttum MS, Kivlin JD, Hong P. Outcome of surgery for esotropia in children with down syndrome. Am Orthopt J. 2004;54(1):98-101.

20. Motley WW 3rd, Melson AT, Gray ME, Salisbury SR. Outcomes of strabismus surgery for esotropia in children with Down syndrome compared with matched controls. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;49(4):211-4; quis 210,215.

21. Perez CI, Zuazo F, Zanolli MT, Guerra JP, Acuña O, Iturriaga H. Esotropia surgery in children with Down syndrome. J AAPOS. 2013;17(5):477-9.

22. Gurez C, Ocak OB, Inal A, Aygit ED, Celik S, Huseyinhan Z, et al. Surgical dose-response relationship in patients with down syndrome with esotropia; a comparative study. J AAPOS. 2018;22(4):e45-e46.

23. Hopker LM, Weakley DR. Surgical results after one-muscle recession for correction of horizontal sensory strabismus in children. J AAPOS. 2013;17(2):174-6.

24. Issaho DC, Wang SX, de Freitas D, Weakley DR Jr. Variability in response to bilateral medial rectus recessions in infantile esotropia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2016;53(5):305-10.

25. Alnajjar T, Sesma G, Alfreihi S. Conventional surgery versus botulinum toxin injection for the management of esotropia in children with Down syndrome. J AAPOS. 2022;26(5):251.e1-251.e4.

26. Dumitrescu AV, Moga DC, Longmuir SQ, Olson RJ, Drack AV. Prevalence and characteristics of abnormal head posture in children with Down syndrome: a 20-year retrospective, descriptive review. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(9):1859-64.

27. Kutti Sridharan G, Rokkam VR. Macroglossia. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls; 2025.[cited 2025 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560545/

Submitted for publication:

February 21, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

July 18, 2025.

Approved by the following research ethics committee: Associação de Pais e Amigos dos Excepcionais de São Paulo - APAE (CAAE: 63114822.7.0000.8647).

Data Availability Statement: The datasets produced and/or analyzed in this study can be provided to referees upon request.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior

Associate Editor: Luisa M. Hopker

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.