Claudia R. Morgado1; Marcony R. Santhiago1; Antonio Marcelo B. Casella2; Isadora C. Jose2; Beatriz Karine Taba Oguido3; Ana Paula M. T. Oguido2

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2024-0402

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: This study evaluated the proportion of corneas discarded by the Eye Bank of Londrina, Paraná, due to positive serology over a 5-year period and its impact on transplant availability.

METHODS: A cross-sectional study was conducted, analyzing 1,968 corneas from 1,056 donors collected between January 2014 and December 2018 at the Eye Bank of Londrina. Serological tests for hepatitis B (HBsAg and anti-HBc), hepatitis C (anti-HCV), and HIV (anti-HIV 1 and 2) were performed using chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassays. Data were analyzed descriptively and presented in tables and graphs.

RESULTS: Of the 1,968 corneas processed, 897 (45.57%) were discarded. Among these, 333 (37.12%) tested positive for serological markers. Hepatitis B accounted for 34.67% of positive cases (15% of total donations), hepatitis C for 1.11% (0.50% of total), and HIV for 0.89% (0.4% of total). Hepatitis cases remained stable between 2014 and 2016, with a marked decline in 2017 and 2018. Most discarded corneas were positive for anti-HBc (31.88%) and negative for HBsAg; however, the anti-HBs test was not performed to confirm immunity to the hepatitis B virus.

CONCLUSION: The findings highlight the importance of serological testing to identify and eliminate contaminated corneas, thereby preventing the transmission of infectious diseases to recipients. Positive serology for hepatitis, particularly hepatitis B, was the leading cause of corneal disposal.

Keywords: Cornea; Corneal transplantation; Corneal donation; Eye banks; Hepatitis B virus; Hepatitis C virus; HIV infections; Seropositivity; Serologic tests

INTRODUCTION

Corneal transplantation has been performed since the early 20th century to restore visual acuity in patients with corneal pathologies. Globally, it remains the most successful form of allogeneic human tissue transplantation(1,2). Corneal tissue is most commonly used for young patients with keratoconus and older individuals with endothelial dysfunction(3).

Over time, systems have been developed and regulated to improve the storage, preservation, and distribution of ocular tissues(1). General standards are regularly reviewed to ensure the safety and quality of allografts(3). Eye banks are responsible for evaluating the quality of donated corneas, selecting donors, and performing serological screening tests to reduce the risk of disease transmission to recipients(3-6). They also oversee the processing, packaging, evaluation, and distribution of corneas and sclerae, maintaining quality at every stage. Brazilian legislation, guided by ANVISA and in alignment with international regulatory bodies, prohibits the transplantation of corneas from donors who test positive for hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), HIV, or HTLV-1/2(1,4,5,7-11).

Hepatitis B is a significant public health concern and remains a leading cause of corneal disposal, despite the availability of vaccination programs(4,8,9,12,13). The HBV vaccine was introduced in 1998 by the National Immunization Program of the Ministry of Health (MS) for newborns and, in 2001, extended to individuals up to 19 years of age. According to the MS, viral hepatitis has a major impact on morbidity and mortality within the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS).

The objective of this study was to determine the percentage of corneas discarded by the Londrina Eye Bank (BOL) due to positive serology over a 5-year period and to assess the overall impact of this disposal on corneal availability.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Beings of the State University of Londrina on September 13, 2019.

A cross-sectional design was used, based on data from the production records of the Eye Bank of Londrina (BOL) at the Regional University Hospital of Northern Paraná. The study covered the period from January 2014 to December 2018 and included 1,968 corneas preserved at BOL from 1,056 donors. Serological data collected from the donors were analyzed for hepatitis B (HBsAg and anti-HBc), hepatitis C (anti-HCV), and HIV (anti-HIV 1 and 2).

Serological testing was performed on donor blood samples at the chemical analysis laboratory of the University Hospital of Londrina. The chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) method was used for the qualitative detection of antibodies against hepatitis B core and surface antigens (anti-HBc and HBsAg), hepatitis C antigen (anti-HCV), the p24 antigen of HIV, and antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and/or 2 (HIV-1/HIV-2) in serum and plasma, including postmortem samples.

Data were analyzed using descriptive quantitative statistics, with results presented in tables and graphs. Variables included serological results for HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HCV, and anti-HIV 1 and 2.

RESULTS

During the study period, 1,968 corneas were processed, of which 897 (45.57%) were discarded. Reasons for discard included reactive results for HBsAg or anti-HBc, positive tests for anti-HCV and HIV 1 and 2, absence of serological data, poor tissue quality, and contamination. Of these, 333 corneas were excluded due to positive serological results, representing 37.12% (333/897) of all discarded corneas.

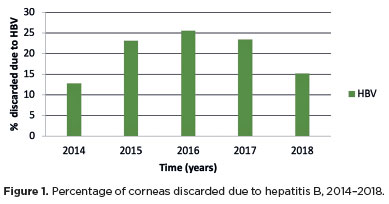

Among the discarded corneas, 34.67% (311/897) tested positive for hepatitis B (HBV) markers, corresponding to 15% (311/1,968) of all donations. For hepatitis C, 1.11% (10/897) tested positive, representing 0.50% (10/1,968) of the total corneas. HIV 1 and 2 positivity was detected in 0.89% (8/897) of discarded corneas, equivalent to 0.4% (8/1,968) of donations. The proportion of corneal discards due to hepatitis B increased between 2014 and 2016, followed by a decline in 2017 and 2018 (Figure 1).

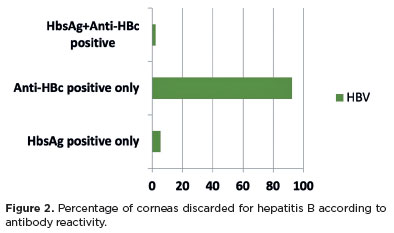

Corneas positive for anti-HBc but negative for HBsAg accounted for the majority of cases, comprising 31.88% (286/897) of the discarded corneas (Figure 2). Notably, anti-HBs testing was not performed to confirm HBV immunity.

DISCUSSION

One of the main reasons for discarding donor corneas is positive serological results(5,7). Reports from the literature indicate that between 1984 and 1985, cases of HBV infection occurred following penetrating corneal transplantation in the United States. In response, human eye banks implemented screening procedures, and in 1990, the Food and Drug Administration established a regulatory framework for the American eye bank system(1,5,6,11,13,14).

The Eye Bank Association of America uses HBsAg testing to screen for hepatitis B. In Brazil, when corneas are positive for anti-HBc and non-reactive for HBsAg, it is left to the discretion of the eye and tissue bank to perform anti-HBs testing to confirm HBV immunity. If the anti-HBs test is reactive, a risk assessment is conducted to decide on donor acceptance. Screening for hepatitis C and HIV follows similar protocols in both settings(8,12,15).

International studies report positive hepatitis B serology rates ranging from 0.92% to 3% of donations. However, a study at the Eye Bank of Hospital São Paulo (2006–2007) found a higher rate of 10.4%(10–12). In another Brazilian study (2011, Eye Bank of Cascavel), the discard rate due to hepatitis B was 47.4% when considering anti-HBc and/or HBsAg, but only 1.5% when both markers were analyzed together, a figure closer to international averages(7,12). At the Irmandade Santa Casa de Porto Alegre Eye Bank, 23% of corneas were discarded for positive serologies, most frequently anti-HBc, followed by anti-HCV and HIV. In Minas Gerais, the discard rate reached 46% in 2007(16).

In our study, the overall discard rate due to positive serology (HBV, HCV, HIV) was 37.12%. Of these, 15% of donations tested positive for hepatitis B, accounting for 34.6% of all discards. When only HBsAg-positive markers were considered, the discard rate decreased to 2%, consistent with other studies(7,12).

The high frequency of isolated anti-HBc reactivity, compared with the lower prevalence of HBsAg positivity, requires careful interpretation. This discrepancy suggests a high potential for false-positive anti-HBc results, as previously reported in the literature, with post-mortem sample degradation further affecting assay accuracy. Isolated anti-HBc positivity may represent past infections resolved with clearance of HBsAg and anti-HBs. However, in the absence of detectable anti-HBs, distinguishing between resolved infection and false positivity is difficult. Although occult HBV infection remains possible, the transmission risk is minimal when HBsAg and HBV DNA are negative. Thus, most isolated anti-HBc cases among cadaveric donors likely reflect past infection or false reactivity due to assay limitations. These findings emphasize the need for confirmatory testing, such as HBV DNA detection, to better assess the clinical significance of isolated anti-HBc(1,5,7,8,12).

Experience over the past five decades has confirmed that donor screening and testing are critical for preventing HBV transmission and ensuring safe transplantation(14). HBsAg testing remains the gold standard for preventing transplant-related HBV infection(14,17,18). Since the introduction of immunoassays in 1971, test sensitivity has greatly improved, with current assays detecting HBsAg at concentrations as low as 0.1–0.62 ng/mL(14,19). In countries with high HBV prevalence, combining HBsAg and anti-HBc testing provides more reliable donor screening. Some studies recommend nucleic acid amplification testing to reduce false negatives and improve specificity(11,14,20,21). However, the high cost makes this approach impractical in Brazil(11).

Samiee et al.(4) reported a decline in hepatitis B positivity among donors at the Eye Bank of Iran over 3 year, attributed to effective vaccination programs and public health improvements. Similar reductions have been observed in Europe and other endemic regions following vaccination(13,18). In our study, hepatitis B prevalence declined from 2016 onward, possibly reflecting improved vaccination coverage and sanitary conditions nationwide.

Cadaveric donor samples are often of low quality, and false-positive results are common, leading to unnecessary tissue disposal(5). Studies show that as the time between death and blood collection increases, serum is more likely to be hemolyzed, icteric, or turbid. To minimize false positives, blood collection for serology should ideally occur within 12 h post-mortem(5,6).

Lee et al.(22) demonstrated a strong correlation between HCV seropositivity and viral presence in corneal tissue, reinforcing the importance of routine screening. In Western countries, HCV antibody prevalence among blood donors ranges from 0.3% to 1.0%(23). Raj et al.(5,22) found HCV positivity in 0.2% of donated corneas, and none for HIV, results similar to those from the Australian and New Zealand Eye Bank (0.38% HCV). An Israeli study reported a higher HCV discard rate of 6%(21). In our study, hepatitis C accounted for 1.11% of discards (0.50% of donations), while HIV accounted for 0.8% of discards. Compared with national data, our HCV and HIV discard rates were lower than those at the Eye Banks of Santa Casa de Porto Alegre(7) and São Paulo(10), and slightly higher than those in Cascavel.

This study confirms the importance of serological testing for excluding and discarding contaminated corneas, thereby preventing the transmission of infectious diseases to recipients. The most frequent cause of corneal disposal was positive hepatitis serology, particularly for hepatitis B.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Significant contribution to conception and design: Ana Paula M. T. Oguido. Data acquisition: Isadora C. Jose, Beatriz K. T. Oguido. Data analysis and interpretation: Claudia R Morgado. Manuscript drafting: Claudia R Morgado. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Antonio Marcelo B. Casella; Marcony R. Santhiago. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Claudia R. Morgado, Marcony R. Santhiago, Antonio Marcelo B. Casella, Isadora C. Jose, Beatriz K. T. Oguido, Ana Paula M. T. Oguido. Statistical analysis: Claudia R. Morgado. Obtaining funding: not applicable. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Ana Paula M. T. Oguido, Antonio Marcelo B. Casella; Marcony R. Santhiago. Research group leadership: Ana Paula M. T. Oguido.

REFERENCES

1. Schmack I, Ballikaya S, Erber B, Voehringer I, Burkhardt U, Auffarth GU, et al. Validation of spiked postmortem blood samples from cornea donors on the Abbott ARCHITECT and m2000 Systems for viral infections. Transfus Med Hemother. 2020;47(3):236-42.

2. Ple-Plakon PA, Shtein RM. Trends in corneal transplantation: indications and techniques. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(4):300-5.

3. Armitage WJ. Preservation of human cornea. Transfus Med Hemother. 2011;38(2):143-7.

4. Samiee S, Kanavi MR, Javadi MA, Bagheri A, Balagholi S, Hashemi MS. Real time polymerase chain reaction for hepatitis b screening in donor corneas in the central Eye Bank of Iran. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2018;13(4):392-6.

5. Raj A, Mittal G, Bahadur H. Factors affecting the serological testing of cadaveric donor cornea. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66(1):61-5.

6. Challine D, Roudot-Thoraval F, Sabatier P, Dubernet F, Larderie P, Rigot P, et al. Serological viral testing of cadaveric cornea donors. Transplantation. 2006;82(6):788-93.

7. Lunardelli A, Alvarenga AB, Assmann ML, Brum DE, Barison MA. Serological profile of candidates for corneal donation. Rev Bras Oftalmol. 2014;73(5):282-6.

8. Brasil. Ministúrio da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução nº 707, de 1 de julho de 2022. Dispõe sobre o regulamento túcnico para o funcionamento de Bancos de Tecidos oculares de origem humana. Brasília (DF): Ministúrio da Saúde; 2022 [citado 2025 Set 1]. Disponível em: https://anvisalegis.datalegis.net/action/ActionDatalegis.php?acao=categorias&cod_modulo=310&menuOpen=true

9. Hoft RH, Pflugfelder SC, Forster RK, Ullman S, Polack FM, Schiff ER. Clinical evidence for hepatitis B transmission resulting from corneal transplantation. Cornea. 1997;16(2):132-7.

10. Santos CG, Pacini KM, Adán CB, Sato EH. Motivos do descarte de córneas captadas pelo banco de olhos do Hospital São Paulo em dois anos. Rev Bras Oftalmol. 2010;69(1):18-22.

11. Viegas MT, Pessanha LC, Sato EH, Hirai FE, Adán CB. Descarte de córneas por sorologia positiva do doador no Banco de Olhos do Hospital São Paulo: dois anos de estudo. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2009;72(2):180-4.

12. Shiratori CN, Hirai FE, Sato EH. Características dos doadores de córneas do Banco de Olhos de Cascavel: impacto do exame anti-HBc para hepatite B. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2011;74(1):17-20.

13. Ni YH, Huang LM, Chang MH, Yen CJ, Lu CY, You SL, et al. Two decades of universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan: impact and implication for future strategies. Gastroenterology. 2007; 132(4):1287-93.

14. Solves P, Mirabet V, Alvarez M. Hepatitis B transmission by cell and tissue allografts: how safe is safe enough? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(23):7434-41.

15. Borderie VM. Donor selection, retrieval and preparation of donor tissue. In: Bredehorn-Mayr T, Duncker GIW, Armitage WJ, editors. Eye Banking. Basel: Karger; 2009. p. 22-30. [Developments of Ophthalmology Series, 43].

16. Saldanha BO, Oliveira RE Jr, Araújo PL, Pereira WA, Simão Filho C. Causes of nonuse of corneas donated in 2007 in Minas Gerais. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(3):802-3.

17. Nardone A, Anastassopoulou CG, Theeten H, Kriz B, Davidkin I, Thierfelder W, et al. A comparison of hepatitis B seroepidemiology in ten European countries. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137(7):961-9.

18. Pruss A, Caspari G, Krüger DH, Blümel J, Nübling CM, Gürtler L, Gerlich WH. Tissue donation and virus safety: more nucleic acid amplification testing is needed. Transpl Infect Dis. 2010;12(5):375-86.

19. Hollinger FB. Hepatitis B virus infection and transfusion medicine: science and the occult. Transfusion. 2008;48(5):1001-26.

20. Cahane M, Barak A, Goller O, Avni I. The incidence of hepatitis C virus positive serological test results among cornea donors. Cell Tissue Bank. 2000;1(1):81-5.

21. Patel HY, Brookes NH, Moffat L, Sherwin T, Ormonde S, Clover GM, et al. The New Zealand National Eye Bank study 1991-2003: a review of the source and management of corneal tissue. Cornea. 2005;24(5):576-82.

22. Lee HM, Naor J, Alhindi R, Chinfook T, Krajden M, Mazzulli T, et al. Detection of hepatitis C virus in the corneas of seropositive donors. Cornea. 2001;20(1):37-40.

23. Machin H. Corneal transplant tissue – before it reaches the operating room. Int J Ophthalmic Pract. 2014;5(6):205-11.

Submitted for publication:

January 23, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

August 26, 2025.

Approved by the following research ethics committee: Universidade Estadual de Londrina – UEL (CAAE: 20001719.6.0000.5231).

Data Availability Statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included in the manuscript.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior

Associate Editor: Dácio C. Costa

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.