Zhaohui Zhi1; Ying Guo2; Xiaoxin Wang1; Wenxi Jiang1; Yuanzheng Sun1,2

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2024-0362

ABSTRACT

Mucosal-associated invariant T cells are a distinct subset of immune cells primarily located in mucosal tissues, and their role in ocular disorders has recently garnered increasing attention. This review synthesizes recent research on the roles of mucosal-associated invariant T cells in ophthalmology, focusing on their potential involvement in ocular immune responses, inflammation, and related diseases. By thoroughly analyzing current findings, this paper aims to novel insights that may guide future clinical applications in ophthalmology and address existing knowledge gaps regarding the immunomodulatory roles of mucosal-associated invariant T cells in ocular conditions.

Keywords: Mucosal-associated invariant T cells/immunology; Mucous membrane; Eye diseases/immunology; Immunity, humoral; Autoimmune diseases; Inflammation; Dry eye syndromes/immunology; Eye neoplasms/immunology; Eye infections/immunology; Retinal diseases/immunology

INTRODUCTION

Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells are a unique subset of T cells crucial for maintaining immune homeostasis in mucosal tissues. Unlike conventional T cells, MAIT cells recognize microbe-derived metabolites presented by the MR1 molecule. They exhibit characteristic surface markers, including CD3⁺, CD8αα⁺, CD161, and T cell receptor (TCR) Vα7.2. Recent studies have highlighted their significant role in ocular conditions, including autoimmune diseases, infections, and neoplasms. The distinct biological characteristics and functional versatility of MAIT cells make them an important focus of ocular immunology research. This review seeks to explore the current knowledge surrounding MAIT cells, emphasizing on their roles and mechanisms in ocular diseases. Thus, providing insights into possible therapeutic strategies.

Emerging evidence indicates that mucosal tissues, including those associated with the eye, harbor substantial populations of MAIT cells, which can influence the pathogenesis of ocular diseases. Alterations in MAIT cell populations have been observed in autoimmune uveitis, potentially contributing to inflammation by producing cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A/F, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)(1). Their activation and function can also be modulated through interactions with the ocular microbiota, underscoring the importance of the local microenvironment in regulating MAIT cell activity(2).

The potential of targeting MAIT cells in ocular autoimmunity has garnered interest, and studies suggest that enhancing their functionality could provide a novel approach to correct immune dysregulation in various eye diseases(3). Understanding the dual roles of MAIT cells, as protectors and potential contributors to pathology, is essential for developing targeted therapies. As research progresses, MAIT cells stand out as promising candidates for future interventions aimed at restoring immune balance in ocular disorders.

BIOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF MAIT CELLS

MAIT cells are a unique subset of T lymphocytes characterized by their semi-invariant TCR, which recognizes riboflavin biosynthesis metabolites presented by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-related molecule MR1. Although predominantly found in mucosal tissues, such as those of the gastrointestinal tract and respiratory system, MAIT cells are also present in the liver and peripheral blood. Originating in the thymus, they undergo a distinct maturation process influenced by specific cytokines and transcription factors. Notably, their differentiation occurs independently of TCR characteristics during thymic expansion, highlighting their innate-like nature and distinct developmental pathway from conventional T cells(4).

Conversely, ocular mucosal tissues harbor significantly lower MAIT cell densities. Yet, they play critical functions in specific niches and disease contexts. Within the eye, they are present in the subepithelial stromal layer of the conjunctiva, the perivascular stromal regions of the limbus, potentially influencing stem cell niche immunity, and the periductal zones of the lacrimal gland adjacent to secretory cells. The corneal stroma, under normal immune-privileged conditions characterized by reduced MHC-I expression and elevated TGF-β, is largely devoid of MAIT cells. However, during infections like fungal keratitis or invasion, peripheral MAIT cells migrate into the stroma in a CCR6-dependent manner, promoting TNF-α-mediated inflammation or epidermal growth factor–driven repair. In autoimmune disorders such as Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease, MAIT cells infiltrate the choroid and retinal vascular layers, highlighting their dynamic role in ocular immunopathology. This spatial heterogeneity underscores their dual capacity to defend against microbial invasion and maintain tissue-specific immune balance.

ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF MAIT CELLS

MAIT cells originate from double-positive thymocytes expressing CD4 and CD8 coreceptors. CD4 and CD8 are critical surface molecules that bind to MHC class II and I molecules, respectively, influencing T cell antigen recognition and effector functions. During inflammation, CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells can promote or suppress immune responses through distinct subsets and molecular mechanisms. Specifically, CD4⁺ T cells differentiate into effector lineages such as Th1, Th17, and regulatory T cells (Tregs), whereas CD8⁺ T cells exhibit cytotoxic (e.g., CTLs) and regulatory phenotypes (e.g., CD8⁺ Tregs). The balance between immune activation and resolution is regulated by cytokine environments, costimulatory/inhibitory receptor interactions (e.g., CD28/CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1), and tissue-specific cues, underscoring their context-dependent roles in immunopathology and homeostasis.

The development of MAIT cells primarily depends on signals from thymic epithelial cells expressing MR1. The transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein is essential for their differentiation, regulating effector molecule expression. Recent single-cell RNA sequencing studies have revealed complex signaling pathways involved in the maturation of innate T cell subsets, including MAIT cells(5). Additionally, the composition of the microbiota significantly influences MAIT cell development, highlighting the role of environmental factors in shaping the immune repertoire(6).

SURFACE MARKERS AND FUNCTIONAL CHARACTERISTICS OF MAIT CELLS

MAIT cells are defined by the invariant TCR comprising TRAV1-2 and TRAJ33 chains (Figure 1) and the expression of CD161, a marker associated with innate-like T cells. The TRAV1-2 and TRAJ33 chains form the semi-invariant α-chain of MAIT cell TCRs, enabling MR1-restricted recognition of microbial riboflavin metabolites such as 5-OP-RU. This supports their rapid, innate-like antimicrobial responses and links them to immune regulation in infections, autoimmunity, and cancer. This conserved TCR architecture drives the dual functionality of MAIT cells, balancing pathogen defense and tissue homeostasis, and offers therapeutic potential via MR1-targeted immunomodulation. MAIT cells rapidly respond to microbial infections by producing cytokines like IL-17 and IFN-γ upon activation, serving a dual role in immune responses: defending against microbial agents and regulating immune activity.

Recent studies suggest that MAIT cells also have regulatory functions like balancing immune tolerance and inflammatory responses, especially during pregnancy and autoimmune disorders(7,8). This functional versatility underscores their importance in maintaining immune homeostasis and addressing pathogenic challenges.

FUNCTION OF MAIT CELLS IN IMMUNITY

MAIT cells bridge innate and adaptive immunity, and their strategically positioning at mucosal surfaces allows them to rapidly respond to microbial threats. Their involvement in various diseases, including autoimmune disorders and cancer, has garnered significant attention. In autoimmune diseases, MAIT cells may contribute to tissue inflammation and damage, whereas in cancer, their role can be context-dependent, promoting or suppressing tumor growth(9,10). Moreover, MAIT cells interact with other immune cells to enhance the immune response, crucial for pathogen clearance and tumor surveillance(11). MAIT cells may mediate antitumor activity against ocular surface tumors through MR1-restricted recognition of tumor-associated metabolites (e.g., riboflavin derivatives) and the release of cytotoxic granzyme B. However, their dual roles (promoting vs. suppressing tumor growth) are influenced by microenvironmental factors like PD-L1 and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), necessitating further research to harness their therapeutic potential in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Overall, mapping the diverse functions of MAIT cells across various pathological conditions will reveal their potential therapeutic applications in immunotherapy and disease management (Table1).

MAIT CELLS IN OCULAR IMMUNITY

Association between MAIT cells and eye infections

MAIT cells are integral to ocular immune defense. These cells activate upon encountering microbial metabolites presented by MR1, which is expressed on various cell types, including those in the eye. In ocular infections, e.g., those caused by Varicella zoster virus (VZV), MAIT cells contribute to pathogen control through the release of proinflammatory cytokines and cytotoxic factors. Evidence indicates that MAIT cells are pivotal in recognizing and eliminating infected cells, limiting pathogen spread within ocular tissues(12). Their presence in the ocular environment, wherein they respond to microbial threats, underscores their importance in maintaining ocular health. A reduction in MAIT cell functionality may result in chronic infections and ocular diseases, underscoring their importance in immune protection and disease mechanisms(1).

Mechanisms of MAIT cells in ocular inflammation

MAIT cells employ diverse and complex mechanisms in ocular inflammation. Upon activation, they release cytokines, including IFN-γ and TNF-α, which are critical for amplifying inflammatory responses and recruiting additional immune cells to infection or injury sites. Although such responses are essential for pathogen elimination, prolonged activation can lead to tissue damage. In disorders such as uveitis and autoimmune ocular diseases, overactive MAIT cells may exacerbate inflammation and contribute to tissue damage(3). Furthermore, interactions between MAIT cells and other immune populations, such as dendritic cells and neutrophils, help shape the inflammatory milieu. Evidence suggests that neutrophils can suppress MAIT cell activity, underscoring the complexity of immune regulation within ocular environment (Figure 1)(13). Understanding these mechanisms is critical for developing therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating MAIT cell function to enhance treatment efficacy for ocular inflammatory conditions.

Influence of MAIT cells within the ocular tumor microenvironment

MAIT cells are involved in the tumor microenvironment of ocular cancers. Their presence in epithelial-derived tumors, such as ocular melanoma, suggests a potential role in tumor immunity. MAIT cells may exert antitumor effects through cytokine secretion and direct cytotoxicity against malignant cells. However, the ocular tumor microenvironment often contains immunosuppressive elements, which can impair MAIT cell function. Moreover, factors, including immune checkpoint protein expression and immunosuppressive cytokines, may limit MAIT cells' ability to control tumor growth, facilitating immune evasion(14).

Recent studies have explored the potential of MAIT cells in cancer immunotherapy, aiming to enhance their antitumor activity, concurrently mitigating tumor microenvironment–induced immunosuppression(15). In addition to IFN-γ and TNF-α, MAIT cells in tumors can produce cytokines like IL-17 (promotes angiogenesis and immunosuppression), IL-10 (suppresses antitumor immunity), and IL-22 (involved in tissue repair and tumor growth). Their functional orientation is influenced by tumor-derived metabolites (e.g., lactate) and inhibitory checkpoint pathways (e.g., PD-1). This duality, acting as potential tumor suppressing and tumor-promoting agents, underscores their significance in ocular oncology and highlights the need for further mechanistic studies.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN MAIT CELLS AND EYE DISEASES

MAIT cells in autoimmune eye diseases

MAIT cells are involved in the pathogenesis of autoimmune eye diseases. As a subset of innate-like T cells, these cells recognize microbial vitamin B metabolites presented by MR1. Activation of MAIT cells can trigger inflammatory responses in ocular tissues. Studies suggest that MAIT cells play a role in the development and progression of autoimmune conditions affecting the eye, including ocular diseases (Figure 1), potentially serving as targets for therapeutic intervention.

Owing to their unique utilization of TCR, these cells are pivotal in the immune system's defense against microbial infections, and are associated with autoimmune conditions like uveitis and other inflammatory diseases affecting the eyes. Depending on the microenvironment and specific antigens, MAIT cells can exert proinflammatory and regulatory effects. In autoimmune uveitis, they can promote tissue damage through cytokine release, whereas in other contexts, they may help regulate immune cell activity and maintain ocular immune tolerance. Recent studies highlight the potential therapeutic benefits of modulating MAIT cell activity in ocular autoimmune disorders, suggesting that fine-tuning their functionality could alleviate disease symptoms and improve patient outcomes(1).

Role of MAIT cells in infectious ocular diseases

MAIT cells are critical for initiating immune responses against pathogens in ocular infections. By recognizing vitamin B metabolites presented by MR1 on antigen-presenting cells, MAIT cells activate and proliferate, leading to the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and co-ordinated pathogen clearance. This includes infections caused by the VZV, which has been shown to infect MAIT cells and potentially alter their function, contributing to the development of viral keratitis. The rapid response of MAIT cells to infectious agents highlights their critical involvement in the management of ocular infections; however, any dysfunction in these cells may result in persistent infections and chronic inflammatory conditions(12). In normal physiology, the corneal stroma is largely devoid of MAIT cells owing to its immune privilege, characterized by low MHC-I expression, high TGF-β levels, and an immune-quiescent state. During infection or inflammation, such as in fungal keratitis, peripheral MAIT cells migrate into the stroma via CCR6–CCL20 chemotaxis. In the limbus (corneoscleral junction), small populations of MAIT cells are present in perivascular stromal regions, where they may interact with limbal stem cells to regulate local immune surveillance and tissue repair.

Potential role of MAIT cells in ocular tumors

Owing to current research advances, MAIT cells are believed to have a significant involvement in ocular tumor progression. Studies have identified MAIT cells in the tumor microenvironment of ocular malignancies, especially uveal melanoma, potentially influencing tumor progression and the immune landscape. MAIT cells exhibit a dual role in ocular oncology, demonstrating antitumor immunity through cytotoxic activity and cytokine production, while potentially facilitating tumor immune evasion. Understanding these interactions with tumor cells could provide insights for developing new immunotherapies for ocular cancers(15).

LATEST RESEARCH FINDINGS

Research progress on MAIT cells in dry eye disease

MAIT cells have gained considerable attention in recent research on dry eye disease (DED), a multifactorial condition characterized by ocular surface inflammation and damage. MAIT cells contribute to DED pathogenesis by participating in inflammatory processes within mucosal tissues. Upon activation by microbial metabolites, these cells produce proinflammatory cytokines (notably IFN-γ and TNF-α) that exacerbate ocular surface inflammation. Moreover, MAIT cell activation through bacterial antigens increases IFN-γ and TNF-α concentration, key mediators of inflammation in DED(1).

Changes in MAIT cell prevalence and function have been observed in patients with DED, suggesting their potential as biomarkers for evaluating disease severity and progression. Understanding how MAIT cells affect DED could lead to the development of novel therapies that alter immune responses to restore ocular surface health. MAIT cells migrate to inflammatory sites through chemokine receptor pathways, such as CCR6–CCL20 and CXCR6–CXCL16, in response to infection or tissue damage. Infiltration into inflamed tissues, including the cornea during keratitis, gut in colitis, and joints in rheumatoid arthritis, is associated with protective functions (pathogen clearance via granzyme B and cytokine release (IFN-γ/TNF-α)) and pathological outcomes (IL-17-mediated tissue damage). Their recruitment and functional profile are context-dependent, balancing host defense and the preservation of tissue homeostasis.

The link between MAIT cells and retinal disorders

Emerging research on MAIT cells in retinal disorders highlights the critical role of the immune system in maintaining ocular health. Recent studies have begun to elucidate the role of MAIT cells in the development and progression of eye disorders such as diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). It has been established that MAIT cells interact with retinal pigment epithelium cells, triggering the release of inflammatory cytokines that may contribute to retinal injury(1).

In diabetic retinopathy, dysregulated MAIT cell activity can intensify chronic inflammation, leading to increased vascular permeability and neovascularization. Additionally, researchers are investigating the role of MAIT cells in preserving retinal homeostasis by identifying and eliminating microbial pathogens. This dual role, as protectors against retinal degeneration and as potential drivers of pathology, highlights the need for further studies to fully define their contribution to retinal disease progression and prevention.

MAIT cells in ocular transplantation

In ocular transplantation, MAIT cells have emerged as crucial modulators of immune responses. with the potential to influence graft tolerance and rejection. This immunoregulatory functions highlight their potential as therapeutic targets in improving transplant outcomes. Consequently, interest in MAIT cells is increasing in ocular transplantation.

The immunological landscape of transplant rejection is complex, and MAIT cells may influence the outcome of corneal and retinal transplants through their unique antigen recognition capabilities. Recent findings suggest that MAIT cells can recognize non-peptide antigens presented by MR1 molecules, which may be expressed in donor tissues (Figure 1)(16). This recognition can elicit protective immune responses that promote graft tolerance or detrimental responses that result in rejection. Understanding the balance of MAIT cell activation in the transplant setting is crucial for improving graft survival rates. Additionally, strategies aimed at modulating MAIT cell responses could be developed to enhance acceptance of ocular grafts. Ongoing research into MAIT cells in ocular transplantation may lead to new immunotherapeutic strategies to enhance transplant success and reduce complications.

The potential for clinical applications of MAIT cells

Numerous studies have demonstrated that MAIT cells possess distinct characteristics and functions, underscoring their potential in clinical applications. These unique T cells are integral to immune responses against diverse pathogens and are implicated in a variety of diseases. Their clinical potential encompasses three primary areas: use as biomarkers, applications in ophthalmological therapies, and exploration of future research directions alongside potential challenges.

The role of MAIT cells as biomarkers

MAIT cells have emerged as promising biomarkers in diverse clinical settings. Their TCR repertoire and activation status provide valuable insights into a patient's immune profile. Studies suggest that the invariant chain linked with the MAIT-TCR could serve as a novel diagnostic biomarker for conditions such as keloids. The presence and functionality of MAIT cells are associated with disease severity and progression(17). Alterations in MAIT cell populations have been reported in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, suggesting their involvement in disease pathogenesis and progression(18).

Assessing levels and functional capacity of MAIT cells may enhance patient stratification and enable personalized therapeutic strategies. This is particularly relevant in non-small cell lung cancer, where circulating CXCR6-positive MAIT cells correlate with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy effectiveness(19). Collectively, research into MAIT cells as potential biomarkers offers opportunities to improve diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes across a spectrum of diseases.

Potential applications of mait cells in ocular therapies

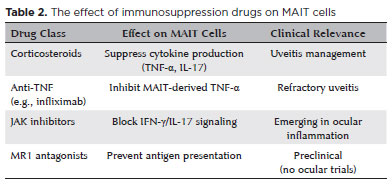

MAIT cells may play a pivotal role in ocular diseases involving inflammation and infection. Given their significance in mucosal immunity, MAIT cells hold significant therapeutic promise. Evidence suggests MAIT cell activation in ocular conditions such as uveitis and AMD, where they may contribute to the pathophysiological mechanisms underlining these disorders. Modulating MAIT cell activity could inspire novel treatment strategies for treating these conditions; for instance, enhancing pathogen clearance or regulating inflammatory responses to reduce tissue damage and preserve vision. Furthermore, MAIT cells may be explored in ocular tumor immunotherapy As our understanding of MAIT cell functions in ocular health and disease evolves, their therapeutic applications could significantly reshape clinical practices. Although no drug targets MAIT cells specifically, recent findings suggests that certain immunosuppressive agents may indirectly affect their activity (Table 2). Emerging evidence also suggests that vitamin D and its receptor signaling may modulate MAIT cell function, promoting anti-inflammatory IL-10 and suppressing IL-17 in autoimmune contexts, though direct mechanistic links remain unclear. Although clinical observations have noted altered MAIT cell activity in vitamin D-deficient individuals, the effects are context-dependent (pro- or anti-inflammatory) and require validation.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS AND CHALLENGES

Despite their clinical potential, MAIT cells exhibit numerous research avenues and challenges. Future research should focus on elucidating the mechanisms through which MAIT cells contribute to immune responses in various diseases as well as their interactions with other immune cells and the microbiota(20). Moreover, standardizing protocols for isolating and characterizing MAIT cells are warranted to ensure reproducibility and comparability across studies. Another challenge is translating basic research on MAIT cells into clinical applications, which demands extensive trials to evaluate their safety and efficacy across diverse patient groups. Additionally, the heterogeneity and functional adaptability of MAIT cell subsets may complicate their use as biomarkers or therapeutic targets. Addressing these obstacles is crucial to fully harness the capabilities of MAIT cells in clinical settings and enhance patient outcomes in various diseases.

Research on MAIT cells in ophthalmology is advancing, highlighting their essential role in ocular immune responses and disorders. Current studies offer significant insights into MAIT cells' contributions to the pathophysiology of various eye conditions. However, it is essential to acknowledge that the findings, although promising, present a spectrum of perspectives that require a balanced interpretation.

The diverse functions of MAIT cells, coupled with their unique activation mechanisms, suggest a multifaceted impact on ocular health. Some studies indicate a protective role against infections, whereas others raise concerns about their involvement in autoimmune processes. This dichotomy underscores the necessity for further investigation into the specific mechanisms through which MAIT cells operate in different ocular diseases. Future research should focus on clarifying how MAIT cells drive protective and pathogenic responses in the eye. Understanding these nuances will be critical in developing targeted therapeutic strategies that harness the beneficial aspects of MAIT cell activity and mitigate their potential adverse effects. Moreover, the integration of clinical outcomes with laboratory findings will be paramount in translating basic research into practical applications. MAIT cells have the potential to cure a wide range of ocular diseases; however, their therapeutic application requires a multidisciplinary approach involving immunology, ophthalmology, and clinical practice.

As research in this area progresses, it may pave the way for innovative interventions that could improve disease prevention and treatment strategies in ophthalmology. Integrating diverse perspectives and research outcomes enhances our understanding of MAIT cells' role in ocular health maintenance, improving our ability to treat and manage ocular disorders.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS:

Significant contribution to conception and design: ZhaoHui Zhi, Yuanzheng Sun. Data Acquisition: ZhaoHui Zhi, Ying Guo, Xiaoxin Wang, Wenxi Jiang. Data Analysis and Interpretation: ZhaoHui Zhi, Ying Guo, Xiaoxin Wang, Wenxi Jiang. Manuscript Drafting: ZhaoHui Zhi. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Yuanzheng Sun. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: ZhaoHui Zhi, Ying Guo, Xiaoxin Wang, Wenxi Jiang, Yuanzheng Sun. Statistical analysis: ZhaoHui Zhi, Ying Guo, Xiaoxin Wang, Wenxi Jiang. Obtaining funding: not applicable. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Yuanzheng Sun. Research group leadership: Yuanzheng Sun.

REFERENCES

1. Fukui C, Yamana S, Xue Y, Shirane M, Tsutsui H, Asahara K, et al. Functions of mucosal associated invariant T cells in eye diseases. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1341180.

2. Godfrey DI, Koay HF, McCluskey J, Gherardin NA. The biology and functional importance of MAIT cells. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(9):1110-28.

3. Yamana S, Shibata K, Hasegawa E, Arima M, Shimokawa S, Yawata N, et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells have therapeutic potential against ocular autoimmunity. Mucosal Immunol. 2022;15(2):351-61.

4. Karnaukhov VK, Le Gac A, Bilonda Mutala L, Darbois A, Perrin L, Legoux F, et al. Innate-like T cell subset commitment in the murine thymus is independent of TCR characteristics and occurs during proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2024;121(14):e2311348121.

5. Lee M, Lee E, Han SK, Choi YH, Kwon DI, Choi H, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies shared differentiation paths of mouse thymic innate T cells. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4367.

6. Wang NI, Ninkov M, Haeryfar SM. Classic costimulatory interactions in MAIT cell responses: from gene expression to immune regulation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2023;213(1):50-66.

7. Raffetseder J, Lindau R, van der Veen S, Berg G, Larsson M, Ernerudh J. MAIT cells balance the requirements for immune tolerance and anti-microbial defense during pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:718168.

8. Zhang T, Huang C, Luo H, Li J, Huang H, Liu X, et al. Identification of key genes and immune profile in limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension by bioinformatics analysis. Life Sci. 2021;271(10103):119151.

9. O'Neill C, Cassidy FC, O'Shea D, Hogan AE. Mucosal associated invariant T cells in cancer-friend or foe? Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(7):1582.

10. Zhang B, Chen P, Zhu J, Lu Y. The quantity, function and anti-tumor effect of mucosal associated invariant T cells in patients with bladder cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;133:111892.

11. Xiao MH, Wu S, Liang P, Ma D, Zhang J, Chen H, et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells promote ductular reaction through amphiregulin in biliary atresia. EBioMedicine. 2024;103:105138.

12. Purohit SK, Corbett AJ, Slobedman B, Abendroth A. Varicella zoster virus infects mucosal associated invariant T cells. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1121714.

13. Schneider M, Hannaway RF, Lamichhane R, de la Harpe SM, Tyndall JD, Vernall AJ, et al. Neutrophils suppress mucosal-associated invariant T cells in humans. Eur J Immunol. 2020;50(5):643-55.

14. Zumwalde NA, Gumperz JE. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells in tumors of epithelial origin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1224: 63-77.

15. Li YR, Zhou K, Wilson M, Kramer A, Zhu Y, Dawson N, et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Ther. 2023;31(3):631-46.

16. Toubal A, Nel I, Lotersztajn S, Lehuen A. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(10): 643-57.

17. Nurzat Y, Zhu Z, Zhang Y, Xu H. Invariant chain of the MAIT-TCR vα7.2-Jα33 as a novel diagnostic biomarker for keloids. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32(2):186-97.

18. Wei L, Chen Z, Lv Q. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells display both pathogenic and protective roles in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Amino Acids. 2023;55(12):1819-27.

19. Qu J, Wu B, Chen L, Wen Z, Fang L, Zheng J, et al. CXCR6-positive circulating mucosal-associated invariant T cells can identify patients with non-small cell lung cancer responding to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43(1):134.

20. Mechelli R, Romano S, Romano C, Morena E, Buscarinu MC, Bigi R, et al. MAIT cells and microbiota in multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases. Microorganisms. 2021;9(6):1132.

Submitted for publication:

November 22, 2024.

Accepted for publication:

July 25, 2025.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study were publicly available from the open-source public database.

Data Availability Statement: The datasets produced and/or analyzed in this study can be provided to referees upon request.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior

Associate Editor: Cristina Muccioli

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.