Nayara Teixeira Flügel1; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama1; Cristine Secco Rosário2; Crislaine Caroline Serpe1; Ana Tereza Ramos Moreira1; Nelson Augusto Rosário Filho6; Herberto Jose Chong Neto2; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello1

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2024-0212

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: To analyze the association between corneal tomography patterns and atopic conditions in children and adolescents, and to investigate the relationship between corneal tomography findings, sleeping position, and dominant hand.

METHODS: Patients aged 8–16 yr underwent ocular and immunological examinations, including biomicroscopy, corneal tomography, the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood questionnaire, and an allergy skin test. Based on immunological results, participants were assigned to either the Control Group or the Atopic Group. Tomographic indices were analyzed alongside information on ocular itching, sleeping position, and dominant hand.

RESULTS: A total of 158 patients (mean age: 10.72 ± 2.13 yr) were evaluated, including 34 (21.52%) in the Control Group and 124 (78.48%) in the Atopic Group. Abnormal tomography was observed in 25 patients (15.82%), while 133 (84.18%) had normal results. Comparison between the Control and Atopic Groups regarding ocular itching episodes revealed a statistically significant difference (p≤0.05). Dominant hand and sleeping position showed no statistically significant associations with group classification, tomography results, or ocular itching.

CONCLUSION: Systemic allergies are strongly associated with biomechanical and structural corneal changes, which may or may not progress to different keratoconus patterns. No association was found between eye rubbing and any tomographic parameter, nor between sleeping position or hand dominance and tomography findings.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Hypersensitivity; Hypersensitivity, immediate; Cornea; Skin tests; Sleep; Tomography.

INTRODUCTION

Keratoconus is a progressive, asymmetrical corneal ectasia that usually manifests in the second decade of life(1). The earlier the onset, the faster the progression, and the greater the severity of the disease(2,3). If left untreated, keratoconus can lead to structural ocular changes, progressive visual loss, and a decline in patients' quality of life(4,5). Current treatment options can stabilize disease progression, improve visual quality, and even rehabilitate vision in advanced stages(6).

Allergic diseases are diagnosed and managed based on clinical history and physical examination. Complementary tests can detect immediate hypersensitivity by identifying specific IgE antibodies either in vitro or in vivo. The skin allergy test, or prick test, is considered the gold standard for diagnosing in vivo allergic sensitization(7). In Brazil, the most frequent allergens are inhalants, particularly house dust mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, and Blomia tropicalis), cockroach allergens (Periplaneta americana and Blattella germanica), pet dander (dog and cat), and fungal allergens(8).

The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), initiated in 1990 to enhance the comparability of epidemiological studies on asthma and allergic diseases, established a standardized protocol that has enabled global research collaboration. Its written questionnaire is a validated tool consisting of three modules addressing asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema(9,10).

This study aims to evaluate the association between corneal tomography patterns and atopic conditions in children and adolescents, using systemic assessments (prick test and ISAAC questionnaire) in conjunction with clinical (ocular biomicroscopy) and complementary (corneal tomography) ophthalmological examinations. Additionally, it investigates the relationship between corneal tomography findings, sleeping position, and hand dominance.

METHODS

This epidemiological, cross-sectional study was conducted at the Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR), Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, from November 2018 to April 2019, and included 158 patients (316 eyes). The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of UFPR (protocol 2.855.765). Ethical principles of data privacy and confidentiality were maintained. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants.

Inclusion criteria were patients aged 8–16 yr who attended the Ophthalmology and Allergy–Immunology outpatient clinics at UFPR during the study period, and who underwent ocular examinations (biomicroscopy and tomography) and immunological testing (allergic skin test) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reliability indices were maintained within recommended limits, and data from the allergy questionnaire were recorded. Only patients with signed informed consent were included.

Exclusion criteria were a history of eye surgery, incomplete data, low-reliability examination results, or ocular alterations on biomicroscopy that could interfere with corneal tomography performance.

Ophthalmological examinations were performed by two ophthalmologists and included slit-lamp biomicroscopy and corneal tomography using the Dual-Scheimpflug System (Galilei G6, Zeimer Ophthalmic Systems AG, Port, Switzerland). Allergy assessments were conducted by a single allergist and included administration of the ISAAC questionnaire (translated and validated in Portuguese) and the prick test.

Based on systemic allergy assessment, patients were divided into two groups: (a) Non-atopic (control) Group (no history of allergy, conjunctivitis, rhinitis, asthma, or dermatitis) and (b) Atopic Group (history of allergic conjunctivitis, rhinitis, asthma, and/or atopic dermatitis).

Allergic conjunctivitis was diagnosed when patients reported experiencing itchy eyes more than three times in the preceding 12 months. Previous studies have shown that this question has a sensitivity of 85.4% and a specificity of 85.2% for diagnosing ocular allergy(11).

The systemic allergy evaluation was performed using the prick test (IMMUNOTECH) with a sterile lancet (ALK Sterile Disposable). Standardized FDA Allergenic extracts for aeroallergens were used, including: two mite species (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Blomia tropicalis), grass pollen mixture, dog epithelium (Canis familiaris), cat epithelium (Felis domesticus), fungal mixture (Aspergillus fumigatus and Alternaria alternata), and cockroach allergens (Periplaneta americana).

Corneal tomography was evaluated by a single experienced ophthalmologist. Patients were classified as having normal tomography (NT) or altered tomography (AT) if any abnormality was detected. Subjective assessment for corneal structural weakness was performed using topographic patterns in association with elevation and pachymetry maps. Tomographic indices included: asphericity (e2), corneal thinnest point (CTP), keratoconus prediction index (KPI), inferior–superior index (I-S), steepest keratometry (K Steep), flattest keratometry (K Flat), maximum keratometry (K Max), best-fit sphere maximum posterior elevation (BFS MPE), best-fit toric asphere maximum posterior elevation (BFTA MPE), asphericity asymmetry index (AAI), cone location and magnitude index (CLMIx), cone location and magnitude index anterior axial (CLMIaa), and coma.

Only one eye per patient was analyzed. The eye with the highest steepest curvature (K Steep) was selected; if both eyes had similar K Steep values, the inferior–superior (I-S) index was used to determine the eye for analysis. For each parameter, the higher value between both eyes was considered (representing the most affected eye).

Patients were also asked about their most frequent sleeping position (right or left side) and were analyzed accordingly in relation to corneal tomography data. Those without a consistent sleeping position were excluded from this analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher's exact test and the Mann–Whitney U test in R statistical software (R Core Team, 2019, version 3.6.1). The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05.

All patients diagnosed with ophthalmological or allergo-immunological disorders were referred for appropriate treatment and follow-up.

RESULTS

A total of 316 eyes from 158 patients were analyzed, of whom 55.70% were male. The mean age was 10.72 ± 2.13 yr (range, 8–16 yr). There was no significant age difference between the control and atopic groups.

Table 1 presents the comparative analysis between the control and atopic groups. Overall, the left eye was the most frequently affected (52.53%), and the majority of participants (91.78%) were right-handed.

Most patients (84.18%) did not present any corneal tomographic abnormality. Only 25 of the 158 patients (15.82%) were diagnosed with subclinical/forme fruste keratoconus (22 patients) or clinical keratoconus (three patients). Of these 25 patients, 92% were in the atopic group (Table 1).

For a more precise assessment of ocular itching, only patients who reported ≥4 episodes of ocular itching in the past year or no episodes at all were included in the analysis. Those who reported one to three episodes in the past year were excluded (n=45).

Table 2 compares ocular itching between the control and atopic groups. The atopic group accounted for the vast majority of cases (80.53%). Only one of the 22 patients in the control group (4.54%) reported ≥4 episodes of ocular itching in the last year, compared with 75 patients (82.42%) in the atopic group. In the atopic group, 16 patients (17.58%) reported no ocular itching. Fisher's exact test revealed a statistically significant difference between the groups (p≤0.05).

No statistically significant differences were observed between the frequency of ocular itching and corneal tomographic classification, gender, dominant eye, or most affected eye (Table 2). Among patients with tomographic abnormalities, 76.19% reported ocular itching, while 23.81% denied ocular itching in the past year.

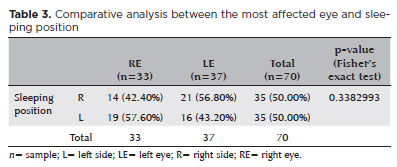

Table 3 presents the comparison between the most affected eye and sleeping position. Only 70 of the 158 participants reported a consistent right- or left-sided sleeping position. Of the 35 patients who reported sleeping on the right side, 21 (60%) had the left eye as the most affected. Conversely, among the 35 patients who slept on the left side, 19 (54.28%) had the right eye as the most affected.

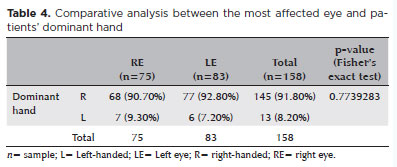

Table 4 shows the relationship between the most affected eye and hand dominance. Of the 158 patients, 91.80% were right-handed, and among them, 53.10% had the left eye as the most affected.

Table 5 compares tomographic parameters between the control and atopic groups, showing no statistically significant differences for any of the analyzed corneal indices.

Table 6 compares tomographic findings between groups with different frequencies of ocular itching. No statistically significant differences were observed. In patients with a higher frequency of ocular itching (Group A), mean asphericity (e2) was 0.36 ± 0.21, compared with 0.31 ± 0.19 in those without ocular itching in the last year (Group B). The overall mean asphericity was 0.34 ± 0.20 (p-value=0.082). The mean AAI was −15.29 ± 13.32 in Group A and −13.00 ± 16.88 in Group B, with an overall mean of −14.54 ± 14.44 (p=0.098).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first in the literature to assess corneal parameters in Brazilian children and adolescents in relation to systemic atopy. The main objective was to integrate immunological data on atopy with corneal shape alterations, aiming to provide a comprehensive dataset that may facilitate earlier diagnosis, halt disease progression, and enable timely implementation of appropriate treatments for corneal disorders(4,5).

The Control Group – negative for allergic reactions – was validated in previous studies through both the prick test and a specific allergy questionnaire. The atopic group consisted of patients with any systemic allergic condition (allergic conjunctivitis, asthma, rhinitis, and/or atopic dermatitis). The relevance of this study lies in the investigation of ocular manifestations in patients with systemic allergy, given that atopy is a recognized cause of chronic eye rubbing – a suspected risk factor for the development and progression of keratoconus(11).

Eye rubbing is generally a benign activity, occurring naturally at various times during the day. However, when performed vigorously, frequently, or for prolonged periods, it becomes pathological and potentially harmful to the cornea. Some authors have proposed a novel theory that eye rubbing is not merely a risk factor, but the primary causal and necessary condition for keratoconus development, encapsulated in the phrase "no friction, no cone". This theory also suggests that halting eye rubbing could stop keratoconus progression, and, more importantly, that preventing mechanical trauma might even eradicate the disease(12,13). Another hypothesis described in the literature is that unilateral keratoconus develops only in the eye subjected to repeated and significant trauma from rubbing(14). These cases imply that keratoconus may arise in otherwise normal eyes in response to a single etiological mechanism – trauma from chronic friction.

In our study, of the 316 eyes evaluated, there was a slight predominance of left-eye involvement (52.53%). Among the 158 patients, 124 were classified as atopic, but only 23 (18.55%) had tomographic abnormalities, with no statistically significant association. When examining the subgroup of 76 atopic patients reporting frequent ocular itching (≥4 episodes in the past year, group A), only 16 (21.05%) showed any tomographic abnormality (subclinical, forme fruste, or clinical keratoconus). In contrast, among atopic patients without ocular itching in the last year (Group B, n=37), 32 (86.46%) had NT (Tables 1 and 2). These findings suggest that experiencing ocular itch within a single year is insufficient to induce measurable corneal alterations. Furthermore, the absence of ocular itching in some systemic atopic patients may be attributed to effective pharmacological or environmental management, indicating that inflammatory changes of atopy may persist subclinically even when symptoms are controlled.

Previous studies have suggested that sleeping position could influence keratoconus development, as sleeping prone or on one side may cause prolonged mechanical pressure on one or both eyes. A strong correlation has been reported between the eye under greater nocturnal pressure and the side with more advanced keratoconus(12,15,16). In our study, only 70 patients reported a consistent right- or left-sided sleeping position. Interestingly, we found an inversion between reported sleeping side and the more affected eye: among 35 right-side sleepers, 21 (60%) had the left eye as the steepest K2; among 35 left-side sleepers, 19 (54.28%) had the right eye most affected (Table 3). This finding suggests that sleeping position may act as a confounding variable in keratoconus pathogenesis and cannot be considered a unique aggravating factor in disease progression.

Another factor discussed in the literature is the correlation between hand dominance and the laterality of keratoconus development. Some studies suggest that friction is more intense when eye rubbing is performed with the dominant hand, leading to more advanced disease in the ipsilateral eye(12,17). In our study (Table 4), this relationship could not be confirmed. Among the 158 evaluated patients, 145 reported right-hand dominance, yet 83 of these had greater keratoconus prevalence in the left eye. Similar to our findings on sleeping position, this suggests that the onset and progression of keratoconus extend beyond the act of ocular itching or rubbing alone.

Table 5 presents the tomographic parameter analysis of the 158 most-affected eyes. These data may assist in distinguishing normal from abnormal corneas in age-matched pediatric populations and may serve as a reference for future comparative studies involving different corneal diseases. Although all parameters were within normal limits, certain patterns differed slightly between the Control and Atopic Groups – particularly in K Steep, asphericity, BFS MPE, BFTA MPE, AAI, CLMIx, and KPI.

For K Steep, the mean value was 43.6 D in the control group and 44.21 D in the atopic group, indicating a slightly steeper meridian in allergic patients, consistent with previous pediatric and adult studies(14,18).

Regarding asphericity, the control group had a mean of 0.29, while the atopic group showed 0.35 (both within normal limits)(19). This parameter becomes particularly relevant when comparing the atopic subgroups A and B (Table 6), as it was among the closest to statistical significance (p=0.082).

BFS and BFTA are non-interchangeable elevation indices. For BFS MPE, the control group had a mean of 11.32 μm, and the atopic group 12.54 μm – both within the normal range (<14 μm) and consistent with literature(18,20). BFTA MPE values averaged 6.94 μm in the control group and 9.64 μm in the atopic group, similar to findings by Smadja et al.(21). Cutoff values have been suggested as >13 μm for subclinical keratoconus and >16 μm for keratoconus.

For AAI, the normal threshold is <21.5 μm(22). In our study, the Control Group mean was 10.29 μm and the atopic group 14.00 μm. Like asphericity, this parameter approached statistical significance (p=0.098) when comparing atopic patients with and without ocular itching (Table 6). AAI remains a valuable screening tool for subclinical keratoconus(20).

CLMIx applies the Cone Location and Magnitude Index strategy to pachymetry, posterior elevation, and posterior curvature maps, rather than just the anterior axial curvature map(23,24). Values range from 0%–25% for normal corneas, 25%–80% for suspicious cases, and 80%–100% for abnormal cases(23). In our study, the mean CLMIx was 4% in controls and 10.23% in the Atopic Group. However, this index was originally designed to differentiate keratoconus and subclinical keratoconus in regular eyes, limiting its applicability here(23).

KPI is considered normal when <10%(25). We found mean values of 4.46% in the Control Group and 7.29% in the Atopic Group, consistent with previous reports(25,26) and well below the thresholds for subclinical keratoconus (>10%) or keratoconus (>30%)(22).

Overall, the relationship between central and peripheral corneal parameters appears different in patients with systemic allergies. While eye rubbing is a known trigger for the onset and progression of keratoconus, in our pediatric cohort, it showed no correlation with tomographic parameters, sleeping position, or hand dominance. The presence of chronic or intermittent systemic allergy instead points to a strong biomechanical and structural component in corneal changes – changes that may or may not progress into keratoconus of varying patterns.

Finally, establishing normative corneal topographic and tomographic values in children and adolescents without systemic allergy or ocular disease is crucial. Such data would enable earlier and more accurate diagnosis of keratoconus in pediatric populations.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS:

Significant contribution to conception and design: Nayara Teixeira Flügel; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama; Cristine Secco Rosário; Crislaine Caroline Serpe; Ana Tereza Ramos Moreira; Nelson Augusto Rosário Filho; Herberto Jose Chong Neto; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello. Data Acquisition: Nayara Teixeira Flügel; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama; Cristine Secco Rosário; Crislaine Caroline Serpe; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello. Data Analysis and Interpretation: Nayara Teixeira Flügel; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama; Cristine Secco Rosário; Crislaine Caroline Serpe; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello. Manuscript Drafting: Nayara Teixeira Flügel; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama; Crislaine Caroline Serpe; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Nayara Teixeira Flügel; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama; Crislaine Caroline Serpe; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Nayara Teixeira Flügel; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama; Cristine Secco Rosário; Crislaine Caroline Serpe; Ana Tereza Ramos Moreira; Nelson Augusto Rosário Filho; Herberto Jose Chong Neto; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello. Statistical analysis: Nayara Teixeira Flügel; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama; Crislaine Caroline Serpe; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello. Obtaining funding: not applicable. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Nayara Teixeira Flügel; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama; Cristine Secco Rosário; Crislaine Caroline Serpe; Ana Tereza Ramos Moreira; Nelson Augusto Rosário Filho; Herberto Jose Chong Neto; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello. Research group leadership: Nayara Teixeira Flügel; Vinícius Tadashi Okuyama; Crislaine Caroline Serpe; Glauco Henrique Reggiani Mello.

REFERENCES

1. Rabinowitz YS. Keratoconus. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42(4):297-319.

2. Mukhtar S, Ambati BK. Pediatric keratoconus: a review of the literature. Int Ophthalmol. 2018;38(5):2257-66.

3. Ertan A, Muftuoglu O. Keratoconus clinical findings according to different age and gender groups. Cornea. 2008;27(10):1109-13.

4. Ferdi AC, Nguyen V, Gore DM, Rozema JJ, Watson SL. Keratoconus natural progression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 529 eyes. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(7):935-45.

5. Aydin Kurna S, Altun A, Gencaga T, Akkaya S, Sengor T. Vision-related quality of life in patients with keratoconus. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014(1):694542.

6. Gomes JA, Tan D, Rapuano CJ, Belin MW, Ambrósio R Jr, Guell JL, Group of Panelists for the Global Delphi Panel of Keratoconus and Ectatic Diseases. Global consensus on keratoconus and ectatic diseases. Cornea. 2015;34(4):359-69.

7. Chong Neto HJ, Rosário NA. Studying specific IgE: in vivo or in vitro. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2009;37(1):31-5.

8. Souza CC, Rosário Filho NA. Perfil de aeroalúrgenos intradomiciliares comuns no Brasil: revisão dos últimos 20 anos. Rev Bras Alerg Imunopatol. 2012;35(2):47-52.

9. Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(3):483-91.

10. Camelo-Nunes IC. Validação construtiva do questionário escrito do "International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood" (ISAAC) e caracterização da asma em adolescentes [tese]. São Paulo: Universidade Federal de São Paulo; 2002.

11. Geraldini M, Chong Neto HJ, Riedi CA, Rosário NA. Epidemiology of ocular allergy and co-morbidities in adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013;89(4):354-60.

12. Najmi H, Mobarki Y, Mania K, Altowairqi B, Basehi M, Mahfouz MS, et al. The correlation between keratoconus and eye rubbing: a review. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019;12(11):1775-81.

13. Gatinel D. Challenging the "No Rub, No Cone" Keratoconus Conjecture. Int J Keratoconus Ectatic Corneal Dis. 2018;7(1):66-81.

14. Gatinel D. Eye rubbing, a sine Qua Non for Keratoconus? Int J Keratoconus Ectatic Corneal Dis. 2016;5(1):6-12.

15. Hashemi H, Pakzad R, Heydarian S, Yekta A, Ostadimoghaddam H, Mortazavi M, et al. Keratoconus Indices and their determinants in healthy eyes of a rural population. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2020;32(4):343-8.

16. Carlson AN. Expanding our understanding of eye rubbing and keratoconus. Cornea. 2010;29(2):245.

17. Lima MH, Rizzi AR, Nepomuceno Neto F, Simoceli RA, Cresta FB, Lima WC, et al. Associação da assimetria do acometimento corneano no ceratocone com a posição preferencial de dormir. eOftalmo. 2016;2(3):1-8.

18. McMonnies CW, Boneham GC. Keratoconus, allergy, itch, eye-rubbing and hand-dominance. Clin Exp Optom. 2003;86(6):376-84.

19. Güler E, Yağci R, Akyol M, Arslanyılmaz Z, Balci M, Hepşen IF. Repeatability and reproducibility of Galilei measurements in normal keratoconic and postrefractive corneas. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014;37(5):331-6.

20. Smadja D, Touboul D, Colin J. Comparative evaluation of elevation, keratometric, pachymetric and wavefront parameters in normal eyes, subclinical keratoconus and keratoconus with a Dual Scheimpflug Analyzer. Int J Keratoconus Ectatic Corneal Dis. 2012;1(3):158-66.

21. Smadja D, Santhiago MR, Mello GR, Krueger RR, Colin J, Touboul D. Influence of the reference surface shape for discriminating between normal corneas, subclinical keratoconus, and keratoconus. J Refract Surg. 2013;29(4):274-81.

22. Feng MT, Kim JT, Ambrósio R Jr, Belin MW, Grewal SP, Yan W, et al. International values of central pachymetry in normal subjects by rotating Scheimpflug camera. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2012;1(1):13-8.

23. Mahmoud AM, Nuñez MX, Blanco C, Koch DD, Wang L, Weikert MP, et al. Expanding the cone location and magnitude index to include corneal thickness and posterior surface information for the detection of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(6): 1102-11.

24. Duncan JK, Esquenazi I, Weikert MP. New diagnostics in corneal ectatic disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2017;57(3):63-74.

25. Feizi S, Yaseri M, Kheiri B. Predictive ability of Galilei to distinguish subclinical keratoconus and keratoconus from normal corneas. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2016;11(1):8-16.

26. Wang X, Dong J, Wu Q. Evaluation of anterior segment parameters and possible influencing factors in normal subjects using a dual Scheimpflug analyzer. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97913.

Submitted for publication:

July 25, 2024.

Accepted for publication:

July 25, 2025.

Approved by the following research ethics committee: UFPR – Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná (CAAE: 95240618.2.0000.0096).

Data Availability Statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included in the manuscript.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior

Associate Editor: Dácio C. Costa

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.