Sung Eun Song Watanabe1; Adriana Berezovsky1; Arthur Gustavo Fernandes1; Bruna Ferraço Marianelli1; João Marcello Furtado1,2; Marcela Cypel1; Paulo Henrique Morales1; Marcos Jacob Cohen3; Cristina Coimbra Cunha1; Márcia Higashi Mitsuhiro1; Galton Carvalho Vasconcelos1,4; Mauro Campos1; Nívea Nunes Ferraz1; Paula Y. Sacai1; Jacob Moysés Cohen3; Sergio Muñoz5; Rubens Belfort Jr.1; Solange Rios Salomão1

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2024-0411

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: This study evaluated macular thickness using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in healthy participants from a population-based eye survey.

METHODS: The Brazilian Amazon Region Eye Survey was a population-based study assessing the prevalence and causes of visual impairment, blindness, and ocular diseases in adults aged ≥45 years from urban and rural areas of Parintins. A subgroup was selected based on inclusion criteria for both eyes: best-corrected visual acuity ≥20/32, normal eye examination results, and no prior ocular surgery. Scans were performed using the iVue optical coherence tomography device. Measurements were taken from the nine subfields defined by the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study, examining the full retina as well as the inner and outer retinal layers. Associations of retinal thickness with age and sex were also analyzed. Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05.

RESULTS: In total, 70 healthy participants (25 males), aged 45–65 years (mean=52 ± 5), were included. Mean central foveal thickness was 248.71 ± 18.73 μm. A significant age-related reduction in macular thickness was observed, particularly in the inner superior parafovea (p=0.036), nasal perifovea (p=0.001), superior perifovea (p=0.028), outer layer of inferior parafovea (p=0.049), and the inferior perifovea of the full retina (p=0.029). Males showed significantly greater thickness in the outer layer, especially in the outer parafovea (p=0.004) and perifovea (p<0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS: This study established normative macular thickness values for healthy older adults in the Brazilian Amazon region using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Age and sex were found to significantly influence macular thickness and should be considered when interpreting measurements. These data will support future studies of retinal diseases in this population.

Keywords: Retinal diseases/diagnosis; Macula lutea/pathology; Macular degeneration/diagnosis; Diabetic retinopathy/diagnosis; Vision, low; Vision tests; Tomography, optical coherence/methods; Young adult; Cross-sectional studies; Brazil/epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive, rapid imaging tool essential in ophthalmology. It provides in vivo images of the retina, optic nerve head, vitreous, and anterior ocular segments, reinforcing its broad role in ocular imaging(1,2). OCT is widely used in clinical settings to address diverse conditions(2). Its utility includes diagnosing age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic macular edema, glaucoma, and retinal vascular diseases(3). OCT can assess structural features, such as macular thickness, the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), and the ganglion cell complex. It is vital for diagnosing and monitoring disease severity or progression by comparison with normal population data(3).

Several studies have shown that factors such as ethnicity, sex, age, and equipment type can affect macular and RNFL thickness measurements(4-7). For instance, a study of 105 Indian subjects(8) reported a lower mean central macular thickness compared with previously published data from a group containing Black, Asian, and predominantly White healthy subjects(9). Another study found that males typically have greater macular thickness compared with females(10). In comparisons involving two or more OCT devices, variations in central macular thickness have been reported in the 2–77-μm range(11).

The Brazilian Amazon Region Eye Survey (BARES) was a population-based study designed to investigate the prevalence and causes of distance and near visual impairment, as well as blindness, among older adults in Parintins, a city in the Amazon Region(12). This region has distinct geographic, demographic, and sociocultural characteristics, differing from other Brazil areas, particularly the Southeast, which has received more pronounced research attention(12,13). Limited health data on this population stems partly from access barriers and logistical challenges faced during the study(14).

The ethnic composition of Amazonian Brazilians reflects a long process of blending that began with indigenous groups and continued with White Europeans (primarily Portuguese), African descendants, and migrants from other Brazilian regions, especially the Northeast during the rubber economic boom(15-17). According to the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) census, 64.8% of the population in the Brazilian Amazon region identifies as multiracial (“pardo”), 25.1% as White, 7.5% as Black, 1.6% as Indigenous, and 1.1% as Asian(18,19).

Research has shown that OCT data can markedly improve accuracy when determining the causes of visual impairment and blindness in various ocular conditions(20,21). However, OCT scans are rarely included in population-based eye surveys, such as BARES, owing to their high cost and complex components, which limit portability. Additionally, these devices often rely on normative databases based primarily on healthy White subjects (reported as Caucasians), which do not represent all populations(22,23).

This study aimed to use spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) to measure macular thickness in the healthy eyes of BARES participants. It also explored potential sociodemographic factors linked to these measurements. The findings may enhance the clinical evaluation of retinal diseases and support diagnosis and treatment monitoring for underserved populations, particularly through future telemedicine protocols.

METHODS

Study design and population

BARES was a population-based, cross-sectional study on the prevalence of near and distance vision impairment and blindness in non-institutionalized residents of Parintins, conducted during September 2013-May 2015. OCT was included in the study to help identify the causes of vision impairment and blindness. However, due to logistical and geographic barriers, OCT was performed only on a subset of participants. The study was approved by the Committee on Ethics for Research of Universidade Federal de São Paulo and Universidade Federal do Amazonas and followed the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Cluster sampling, based on geographically defined census sectors, identified residents aged ≥45 years living in 20 randomly selected clusters (14 urban and 6 rural) in Parintins, located on the margins of the Amazon River, Amazonas State, Brazil. Eligibility was determined via door-to-door surveys, and participants were invited to attend clinical ophthalmic examinations. Inclusion criteria included being at least 45 years old on the day of the household visit and residing in one of the selected clusters for at least the past 6 months. Further details on the study area, eligibility, visual acuity testing, and eye examinations are available elsewhere(12).

The IBGE, defines race considering self-reported skin color including five categories: White, Black, multiracial (mixed White, African, or Indigenous ethnicity), Yellow (Asians), and Indigenous(24).

Ocular examination

The ophthalmic examination included uncorrected visual acuity and acuity with presenting correction, measured using a retro-illuminated logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) tumbling E chart at 4 m. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was determined after autorefraction, followed by subjective refraction, conducted by an ophthalmologist. Biomicroscopy was performed before and after pupil dilation, focusing on lens status, classified as normal, phakic with cataracts, pseudophakic, pseudophakic with posterior capsule opacity, aphakic, aphakic with posterior capsule opacity, or undetermined. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured using applanation tonometry under topical anesthesia after administering 0.5% proxymetacaine hydrochloride eye drops. A fundus examination was also conducted under pupil dilation using 1% tropicamide eye drops.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A subset of BARES participants was selected based on the following inclusion criteria: best-corrected distance visual acuity (BCDVA) of 20/32 or better in each eye, refraction within ±4.0 diopters spherical equivalent, no anterior segment abnormalities based on biomicroscopy observation, and no posterior segment abnormalities in a dilated fundus examination. Additionally, an IOP of ≤21 mmHg was required, as well as no history of ocular surgery. Exclusion criteria included any opacity and a history of glaucoma, diabetes, or ocular trauma.

OCT images acquisition protocol

SD-OCT scans were performed using the iVue-100 SD-OCT device (Optovue Inc., Fremont, California, USA) after pupil dilation. The system’s image acquisition rate was 25,000 A-scans/s, with frame rates between 256 and 1024 A-scans/frame. Optical resolution was 5 μm in depth. Image quality was assessed using the signal strength index (SSI), which measures reflected light intensity. Scans with poor quality were excluded from analysis. For instance, images with segmentation failures, algorithm errors, motion artifacts, poor focus, lack of centering, or SSI below 50 were omitted.

Macular thickness was measured using standard iVue scanning protocols. The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) subfields were used to assess full retinal thickness across nine regions, including parafoveal, perifoveal, nasal, superior, inferior, and temporal areas. Thickness measurements included both inner retinal boundaries (from the internal limiting membrane to the outer limit of the inner plexiform layer) and outer retinal boundaries (from the outer limit of the inner plexiform layer to the retinal pigment epithelium). In total, 29,174 A-scans were analyzed, with a higher sampling density at the central fovea. The EMM5 protocol consisting of a primary macular mapping scan, was used to generate average foveal thickness (1 mm in diameter, centered on the fovea) as well as full, inner, and outer retinal thickness maps.

Statistical analysis

Data from one eye per participant were used for analysis, prioritizing the first tested eye or the eye with better centralization and image quality, provided that both eyes had a BCDVA of 20/32 or better. Descriptive statistics were summarized in frequency tables. Associations between macular thickness and age, sex, education (used as a proxy for socioeconomic status), and ethnicity were examined using multiple linear regression. Statistical analyses were performed in Stata Statistical Software Release 14.0, with statistical significance set at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

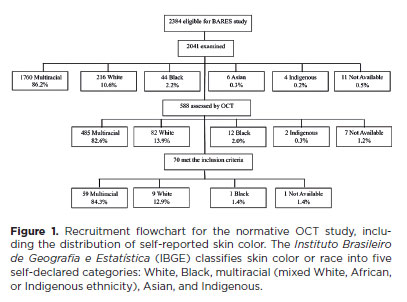

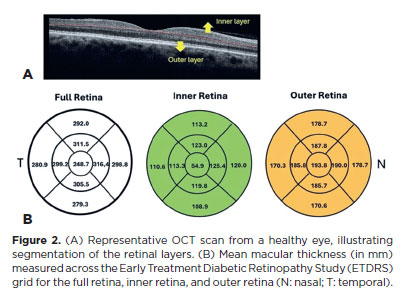

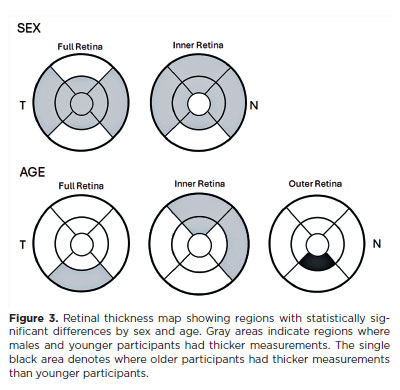

In total, 2,384 eligible individuals were identified, with 2,041 (85.7%) undergoing examination and 588 (28.8%) receiving an OCT assessment. Among this subset, 70 (11.90%) met the inclusion criteria for this study. The flowchart in figure 1 illustrates participant selection, showing that approximately 82% were recorded as multiracial at each stage. Of the 70 participants, 45 (64.29%) were female. The age range was 45–65 years, with a mean age of 52.55 ± 5.78 years. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of participants, including sex, age, education level, and skin color. IOP ranged from 6 to 19 mmHg, with a mean of 12.92 ± 2.44 mmHg. Refractive error in spherical equivalent varied from -1.50 to +2.50 diopters, with a mean of 0.42 ± 0.81 diopters. Supplementary Table 1 lists individual data on sex, age, subjective refraction, and BCVA for each eye.

Macular thickness

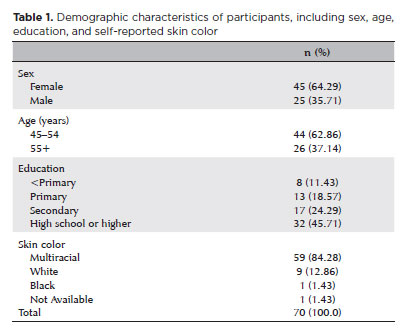

Among the 70 participants, central foveal thickness ranged from 222 to 279 μm, with a mean thickness of 248.71 ± 18.73 μm. Figure 2 presents the mean and standard deviation values for all nine ETDRS subfields, organized into full thickness, inner, and outer retinal layers.

A multiple linear regression model, adjusted for age, sex, education, and skin color, was used to identify factors associated with macular thickness. Age showed a negative association with macular thickness in several subfields. In the inner retina, age was negatively associated with the superior parafoveal (p=0.036), nasal perifoveal (p=0.001), and superior perifoveal (p=0.028) subfields. In the outer retina, the inferior parafoveal (p=0.049) and inferior perifoveal full thickness (p=0.029) areas also showed a negative correlation with age.

Macular thickness was significantly greater in males than in females in the central full thickness subfield (p=0.041), across all parafoveal quadrants, and in the nasal and temporal perifoveal full thickness areas. In the outer retina, males had thicker measurements in four parafoveal quadrants and in the nasal, superior, and temporal perifoveal areas. No sex-based differences were observed in the inner retinal layers (Table 2). Figure 3 shows an OCT retinal thickness map highlighting subfields with statistically significant differences by sex and age.

Qualitative OCT analysis was performed by an experienced OCT examiner (SESW). OCT abnormalities were detected in six eyes, all with 20/20 BCVA and no findings on clinical examination. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, these included drusen in three eyes (participant #9, right eye; participant #30, both eyes), dry AMD with preserved foveal architecture in both eyes of participant #24, and a serous foveal detachment in the right eye of participant #68.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the observed sex effect on foveolar thickness (p=0.041). Controlling for outliers, performing a jackknife analysis, and testing for age–sex interaction effects showed no change in statistical significance. Although the observed association is statistically robust, confirmation in larger population-based samples is recommended.

DISCUSSION

This study has several strengths. First, it used a rigorous sampling methodology. Second, data quality was assured by an experienced team of ophthalmologists and researchers. Third, the analysis focused on the unique characteristics of a specific Amazon population, reinforced by the skin color distribution in the study sample compared with the full BARES cohort. Notably, few population-based studies have reported normative macular thickness values, and to our knowledge, this first to do so in a representative Amazon population.

Variability in macular thickness among SD-OCT systems has been well documented. The present study evaluated macular thickness in a healthy subgroup from a population-based cohort in the Brazilian Amazon region. The mean central foveal thickness was 248.71 ± 18.73 µm, comparable to values obtained using the same Optovue OCT system from 168 healthy White adults with a similar mean age in Bulgaria(26) and 45 healthy Hispanic participants with a similar age range in Colombia(27).

Consistent with previous findings(10,28,29), we found greater macular thickness in males across nearly all regions. As anticipated, macular thickness declined with age in both sexes. All participants had normal BCVA, supporting the exclusion of common vision-impairing conditions, such as cataracts and macular abnormalities. Extensive research on the ETDRS map area has shown that sex and age influence macular thickness. Some studies have associated thicker foveae with male sex and older age(29,30), whereas others found that foveal and macular thickness correlate only with male sex(10). In the present study, males exhibited significantly thicker outer retinal layers, whereas thinning of the inner layers, particularly in the nasal parafoveal area, was associated with aging in both sexes. The observed sex-based difference in outer retinal thickness likely reflects structural variation in the photoreceptor and retinal pigment epithelium layers. This aligns with studies showing that males tend to have thicker combined inner nuclear, outer plexiform, and outer nuclear layers(31). Aging is commonly associated with macular thinning(31-33), although few studies have specified which layers are most affected(31,33,34). Prior research using low-resolution OCT 3 equipment showed age-related thinning of the RNFL(35). The current findings support this, particularly in the perifoveal nasal area, i.e., the thickest part of the macular RNFL.

OCT-based macular thickness measurements vary by device due to differences in technology, retinal layer boundaries, calibration, algorithms, and image acquisition and processing techniques. Therefore, the present study, focusing on an underrepresented ethnic group, may help establish normative macular layer thickness values, with the added value of age and sex subgroup analyses. Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, the age range was 45–65 years, restricting generalizability to other age groups. Second, the sample size was modest (n=70 individuals) compared with larger population-based studies(30,36). Third, the study lacked anatomical variables, such as height and axial length, which may influence OCT parameters(32,34,37). Fourth, the iVue-100 system does not support enhanced depth imaging, preventing analysis of RNFL and choroidal thickness. Finally, logistical barriers to OCT equipment transport in the Amazon Region pose practical challenges.

Despite these limitations, this study provides normative macular thickness data using iVue-100 SD-OCT in healthy adults aged ≥45 years from the Amazon region. These values, derived from a population-based sample, can refine normal OCT reference ranges for this understudied group. These norms may differ from those observed in other populations, such as predominantly White groups typically represented in existing global OCT databases, and improve interpretation of retinal changes, distinguishing normal variation from pathology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq, Brasília, Brasil, Programa Ciência sem Fronteiras (Grant # 402120/2012-4 to SRS, SM and JMF; Research Scholarships to SRS and RBJ); Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, FAPESP, São Paulo, Brasil (Grant # 2013/16397-7 to SRS); SightFirst Program – Lions Club International Foundation (Grant #1758 to SRS).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS:

Significant contribution to conception and design: Sung Eun Song Watanabe, Adriana Berezovsky, Bruna Ferraço Marianelli, Paulo Henrique Morales, Jacob Moysés Cohen, Sérgio Muñoz, Rubens Belfort Jr., Solange Rios Salomão. Data acquisition: Sung Eun Song Watanabe, Adriana Berezovsky, João Marcello Furtado, Marcela Cypel, Paulo Henrique Morales, Marcos Jacob Cohen, Cristina Coimbra Cunha, Márcia Higashi Mitsuhiro, Galton Carvalho Vasconcelos, Mauro Campos, Nívea Nunes Ferraz, Paula Yuri Sacai. Data analysis and interpretation: Sung Eun Song Watanabe, Adriana Berezovsky, Arthur Gustavo Fernandes, Bruna F Marianelli, Sérgio Muñoz, Solange Rios Salomão. Manuscript drafting: Sung Eun Song Watanabe, Adriana Berezovsky, Arthur Gustavo Fernandes, Bruna Ferraço Marianelli, João Marcello Furtado, Marcela Colussi Cypel, Paulo Henrique Morales, Marcos Jacob Cohen, Cristina Coimbra Cunha, Márcia Higashi Mitsuhiro, Galton Carvalho Vasconcelos, Mauro Campos, Nívea Nunes Ferraz, Paula Yuri Sacai, Jacob Moysés Cohen, Sérgio Muñoz, Rubens Belfort Jr., Solange Rios Salomão. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Sung Eun Song Watanabe, Adriana Berezovsky, Arthur Gustavo Fernandes, Bruna Ferraço Marianelli, João Marcello Furtado, Marcela Cypel, Paulo Henrique Morales, Marcos Jacob Cohen, Cristina Coimbra Cunha, Márcia Higashi Mitsuhiro, Galton Carvalho Vasconcelos, Mauro Campos, Nívea Nunes Ferraz, Paula Yuri Sacai, Jacob Moysés Cohen, Sérgio Muñoz, Rubens Belfort Jr., Solange Rios Salomão. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Sung Eun Song Watanabe, Adriana Berezovsky, Arthur Gustavo Fernandes, Bruna Ferraço Marianelli, João Marcello Furtado, Marcela Cypel, Paulo Henrique Morales, Marcos Jacob Cohen, Cristina Coimbra Cunha, Márcia Higashi Mitsuhiro, Galton Carvalho Vasconcelos, Mauro Campos, Nívea Nunes Ferraz, Paula Yuri Sacai, Jacob Moysés Cohen, Sérgio Muñoz, Rubens Belfort Jr., Solange Rios Salomão. Statistical analysis: Arthur Gustavo Fernandes, Sérgio Muñoz. Obtaining funding: Jacob Moysés Cohen, Rubens Belfort Jr., Solange Rios Salomão. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Adriana Berezovsky, João Marcello Furtado, Paulo Henrique Morales, Jacob Moysés Cohen, Sérgio Muñoz, Rubens Belfort Jr., Solange Rios Salomão. Research group leadership: Jacob Moysés Cohen, Rubens Belfort Jr., Solange Rios Salomão.

REFERENCES

1. Hrynchak, P, Simpson T. Optical coherence tomography: an introduction to the technique and its use. Optom Vis Sci. 2000; 77(7):347-56.

2. Thomas D, Duguid G. Optical coherence tomography-a review of the principles and contemporary uses in retinal investigation. Eye (Lond). 2004;18(6):561-70.

3. Jaffe GJ, Caprioli J. Optical Coherence Tomography to detect and manage retinal disease and glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004; 137(1):156-69.

4. Romero-Bascones D, Ayala U, Alberdi A, Erramuzpe A, Galdós M, Gómez-Esteban JC, et al. Spatial characterization of the effect of age and sex on macular layer thicknesses and foveal pit morphology. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0278925.

5. Gupta P, Sidhartha E, Tham YC, Chua DK, Liao J, Cheng CY, et al. Determinants of macular thickness using spectral domain optical coherence tomography in healthy eyes: the Singapore Chinese Eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(13):7968-76.

6. Bentaleb-Machkour Z, Jouffroy E, Rabilloud M, Grange JD, Kodjikian L. Comparison of central macular thickness measured by three OCT models and study of interoperator variability. Sci World J. 2012;2012(1):842795.

7. Bahrami B, Ewe SY, Hong T, Zhu M, Ong G, Luo K, et al. Influence of retinal pathology on the reliability of macular thickness measurement: a comparison between optical coherence tomography devices. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2017;48(4):319-25.

8. Appukuttan B, Giridhar A, Gopalakrishnan M, Sivaprasad S. Normative spectral domain optical coherence tomography data on macular and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in Indians. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(3):316-21.

9. Grover S, Murthy RK, Brar VS, Chalam KV. Normative data for macular thickness by high-definition spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (spectralis). Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(2):266-71.

10. Adhi M, Aziz S, Muhammad K, Adhi M. Macular Thickness by age and gender in healthy eyes using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37638.

11. Wolf-Schnurrbusch UE, Ceklic L, Brinkmann CK, Iliev ME, Frey M, Rothenbuehler SP, et al. Macular thickness measurements in healthy eyes using six different optical coherence tomography instruments. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis Sci. 2009;50(7):3432-7.

12. Salomão SR, Furtado JM, Berezovsky A, Cavascan NN, Ferraz AN Jr, Cohen JM, et al. The Brazilian Amazon Region Eye Survey: design and methods. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017;24(4):257-64.

13. Castro SS, César CL, Carandina L, Barros MB, Alves MC, Goldbaum M. Deficiência visual, auditiva e física: prevalência e fatores associados em estudo de base populacional. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(8):1773-82.

14. Furtado JM, Berezovsky A, Ferraz NN, Muñoz S, Fernandes AG, Watanabe SS, et al. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment and blindness in adults aged 45 years and older from Parintins: The Brazilian Amazon Region Eye Survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2019;26(5):345-54.

15. Carvalho BM, Bortolini MC, Santos SE dos, Ribeiro-dos-Santos ÂK. Mitochondrial DNA mapping of social-biological interactions in Brazilian Amazonian African-descendant populations. Genet Mol Biol. 2008;31(1):12-22.

16. Ferreira RG, Moura MM, Engracia V, Pagotto RC, Alves FP, Camargo LM, et al. Ethnic admixture composition of two western Amazonian populations. Hum Biol. 2002;74(4):607-14.

17. Cancela CD, Cosme JS. Entre fluxos, fontes e trajetórias: imigração portuguesa para uma capital da Amazônia (1850-1920). Estudos Ibero-Americanos. 2016;42(1):232-54.

18. Fraxe TJ, Witkoski AC, Miguez SF. O ser da Amazônia: identidade e invisibilidade. Ciênc Cultura. 2009;61(3):30-2.

19. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. IBGE. Densidade demográfica por países [Internet]. [citado 2025 Mar 19]. Disponível em: https://atlasescolar.ibge.gov.br/mundo/3002-estrutura-e-dinamica-da-populacao/populacao.html

20. Keane PA, Sadda SR. Retinal imaging in the twenty-first century: State of the art and future directions. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(12):2480-9.

21. Ferris FL 3rd, Wilkinson CP, Bird A, Chakravarthy U, Chew E, Csaky K, Sadda SR; Beckman Initiative for Macular Research Classification Committee. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(4):844-51.

22. Realini T, Zangwill LM, Flanagan JG, Garway-Heath D, Patella VM, Johnson CA, et al. Normative Databases for Imaging Instrumentation. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(6):480-3.

23. Nieves-Moreno M, Martínez-de-la-Casa JM, Bambo MP, Morales-Fernández L, Van Keer K, Vandewalle E, et al. New normative database of inner macular layer thickness measured by spectralis OCT used as reference standard for glaucoma detection. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2018;7(1):20.

24. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. IBGE. Base de informações do censo demográfico 2010: resultados do universo por setor censitário [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. [citado 2025 Mar 19]. Disponível em: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010.

25. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. IBGE. Características da população e dos domicílios: resultados do universo [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro; 2010. [citado 2025 Mar 19]. Disponível em: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/caracteristicas_da_populacao/caracteristicas_

da_populacao_tab_municipios_zip_xls.shtm

26. Mitkova-Hristova VT, Konareva-Kostyaneva MI. Macular thickness measurements in healthy eyes using spectral optical coherence tomography. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2011;53(4):28-33.

27. Cortés DA, Roca D, Navarro PI, Rodríguez FJ. Macular and choroidal thicknesses in a healthy Hispanic population evaluated by high-definition spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT). Int J Retina Vitreous. 2020;6(1):66.

28. Kelty PJ, Payne JF, Trivedi RH, Kelty J, Bowie EM, Burger BM. Macular thickness assessment in healthy eyes based on ethnicity using Stratus OCT optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(6):2668-72.

29. Kashani AH, Zimmer-Galler IE, Shah SM, Dustin L, Do DV, Eliott D, et al. Retinal thickness analysis by race, gender, and age using Stratus OCT. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(3):496-502.e1.

30. Duan XR, Liang YB, Friedman DS, Sun LP, Wong TY, Tao QS, et al. Normal macular thickness measurements using optical coherence tomography in healthy eyes of adult Chinese persons: the Handan Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(8):1585-94.

31. Ooto S, Hangai M, Tomidokoro A, Saito H, Araie M, Otani T, et al. Effects of age, sex, and axial length on the three-dimensional profile of normal macular layer structures. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(12):8769-79.

32. Song WK, Lee SC, Lee ES, Kim CY, Kim SS. Macular thickness variations with sex, age, and axial length in healthy subjects: a spectral domain-optical coherence tomography study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(8):3913-8.

33. Neuville JM, Bronson-Castain K, Bearse MA Jr, Ng JS, Harrison WW, Schneck ME, et al. OCT reveals regional differences in macular thickness with age. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86(7):E810-6.

34. Palazon-Cabanes A, Palazon-Cabanes B, Rubio-Velazquez E, Lopez-Bernal MD, Garcia-Medina JJ, Villegas-Perez MP. Normative database for all retinal layer thicknesses using SD-OCT posterior pole algorithm and the effects of age, gender and axial lenght. J Clin Med. 2020;9(10):3317.

35. Eriksson U, Alm A. Macular thickness decreases with age in normal eyes: a study on the macular thickness map protocol in the Stratus OCT. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(11):1448-52.

36. von Hanno T, Lade AC, Mathiesen EB, Peto T, Njølstad I, Bertelsen G. Macular thickness in healthy eyes of adults (N = 4508) and relation to sex, age and refraction: the Tromsø Eye Study (2007–2008). Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95(3):262-9.

37. Lim LS, Saw SM, Jeganathan VS, Tay WT, Aung T, Tong L, et al. Distribution and determinants of ocular biometric parameters in an Asian population: the Singapore Malay eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(1):103-9.

Submitted for publication:

January 6, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

May 9, 2025.

Approved by the following research ethics committee: Universidade Federal de São Paulo-UNIFESP (CAAE: 11830313.6.1001.5505).

Data Availability Statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available on demand from referees.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior

Associate Editor: Caio V. Regatieri

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.