INTRODUCTION

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a rare manifestation of systemic hypertension that requires proper diagnosis and management to avoid irreversible brain damage. Visual disturbances are common, even in absence of funduscopic abnormalities. Early recognition of this condition and prompt control of the patient’s blood pressure are essential because they can bring about a reversal of the syndrome, which may otherwise result in permanent brain damage(1).

CASE REPORT

A 66-year-old white man presented at the emergency room complaining of severe frontal headache, disorientation, and progressive bilateral blurred vision. He had a history of poorly controlled systemic hypertension since the age of 20 years and had experienced an episode of intracerebral hemorrhage 20 years earlier, which had left as squeal bilateral visual field defects and optic neuropathy in the right eye. He was under treatment with amlodipine besylate (10 mg/day) and carvedilol (25 mg/day).

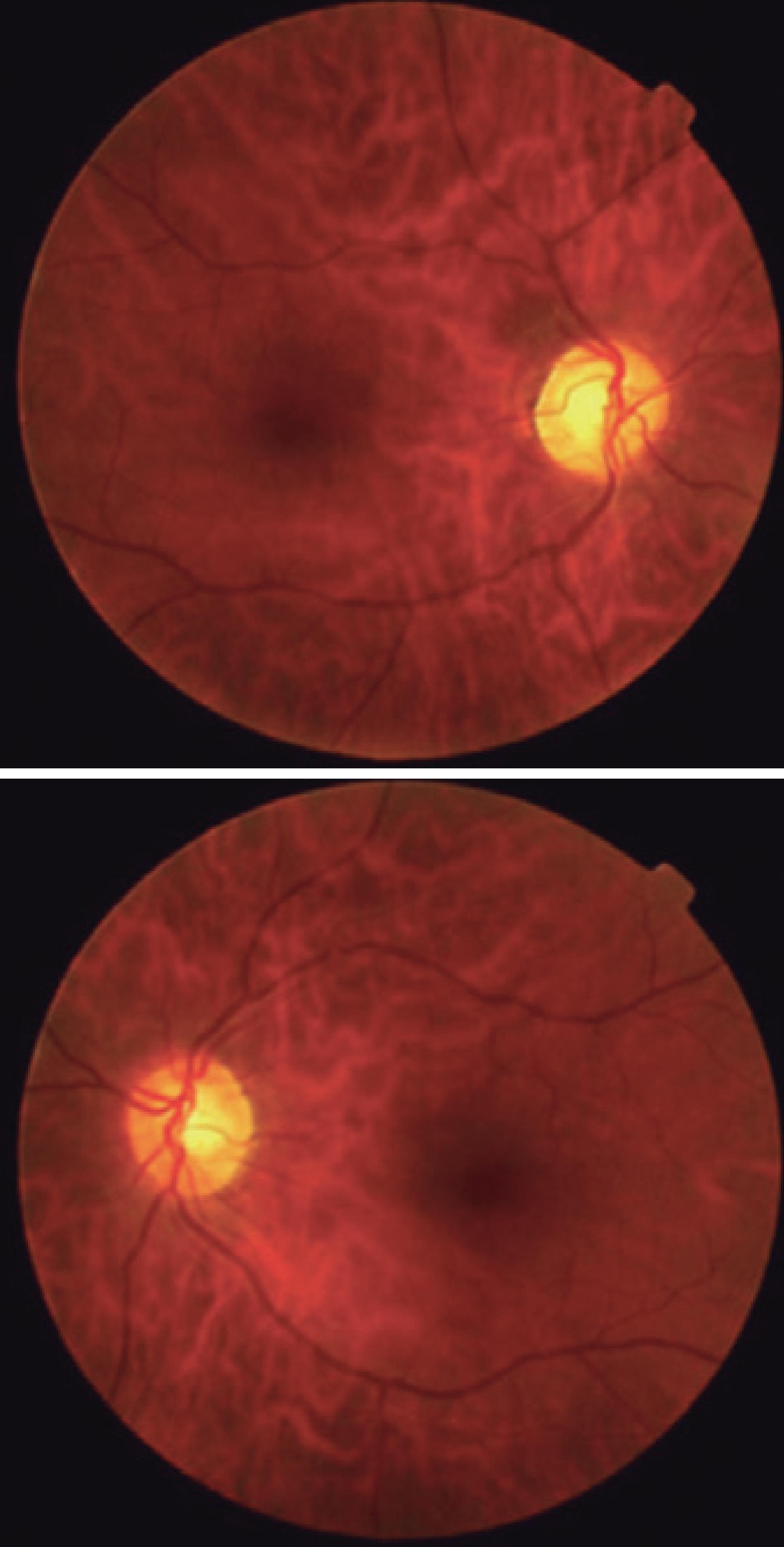

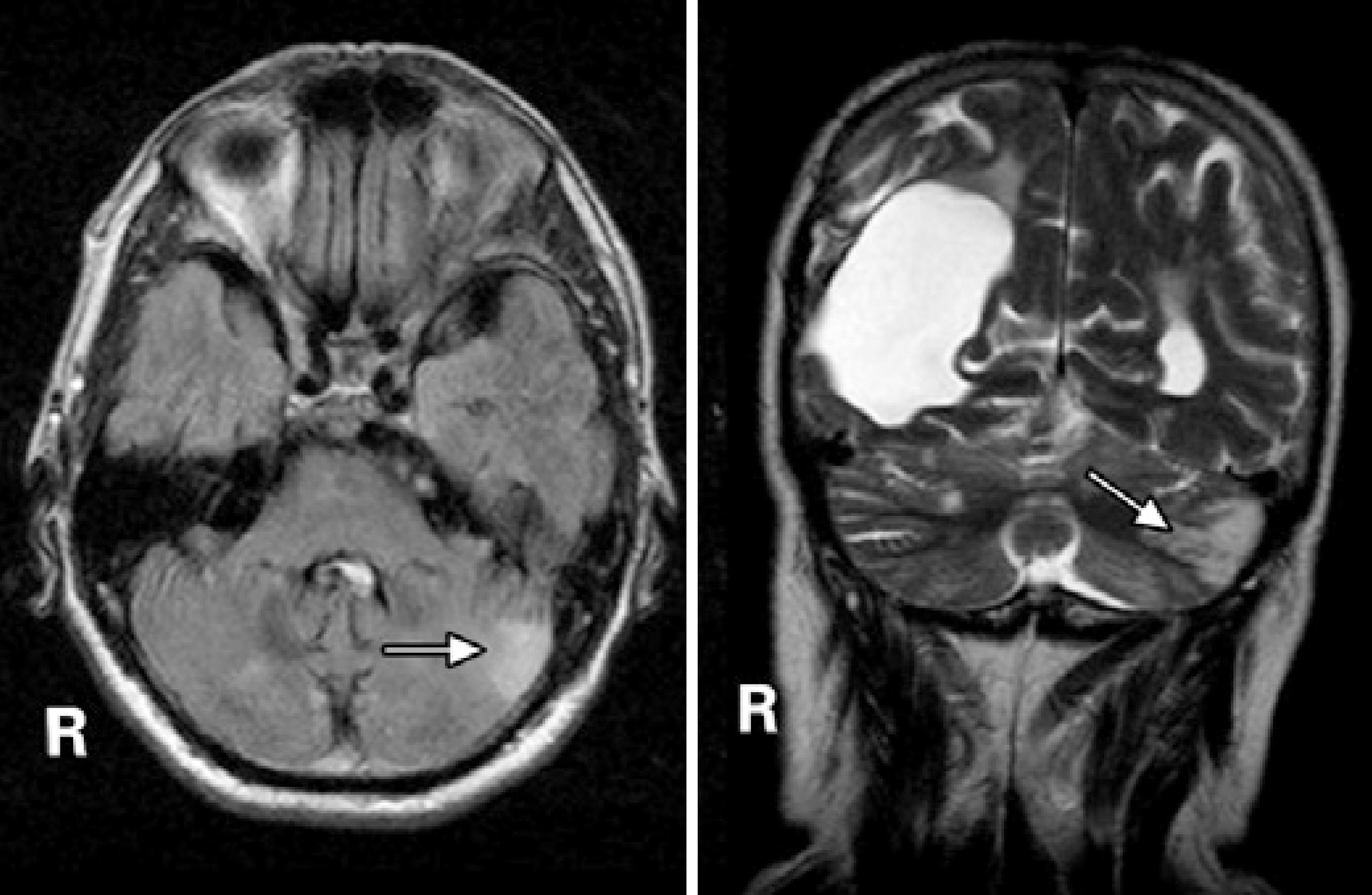

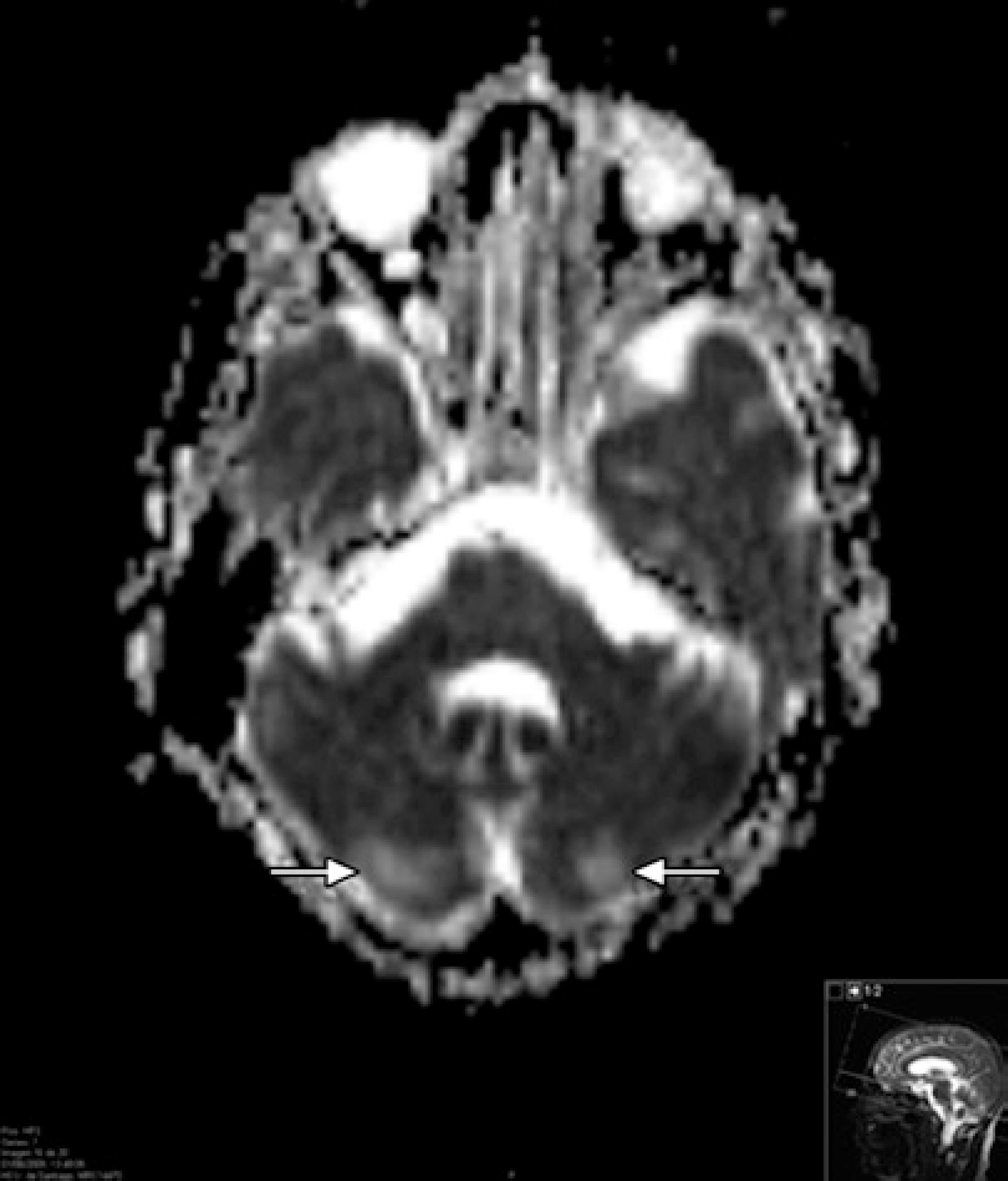

On admission, physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 200/176 mmHg. His visual acuity was classified as “counting fingers” in both eyes, but one hour later it deteriorated to “no light perception” in both eyes. The eye fundus examination was normal (Figure 1). The patient’s pupils were isochoric with a normal light reflex. Neurologic examination showed mental confusion and the electroencephalography revealed slow background activity and the loss of alpha rhythm in the posterior pole. Blood laboratory tests revealed no abnormalities. Electrocardiography and the chest X-ray were normal. An immediate computed tomography (CT) scan was negative for intracranial hemorrhage but showed dilation of the right occipital horn and moderate signs of cortical and subcortical atrophy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquired 24 hours after admission revealed a cortical hyperintense lesion in the left cerebellar hemisphere and an enlarged right ventricle judged to be secondary to a previous infarct (Figure 2). In addition, apparent diffusion coefficient maps obtained during the PRES revealed increased diffusion in the occipital regions indicative of vasogenic edema (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Eye fundus of a 66-year-old man with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. The funduscopic examination of both eyes was normal.

Figure 2 Axial FLAIR-weighted (left) and coronal T2-weighted (right) images showing a hyperintense lesion in the left cerebellar hemisphere (arrows). Note the enlarged right ventricle secondary to a previous infarct.

Figure 3 Apparent diffusion coefficient map for the patient with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. This showed an increased signal in the occipital regions indicative of vasogenic edema.

Three hours after the administration of sublingual nifedipine (10 mg), the patient’s blood pressure decreased to 110/80 mmHg. Treatment was continued with a salt-free diet, losartan (50 mg/day), carvedilol (25 mg/day), and amlodipine besylate (10 mg/day). Two days later, the neurologic signs and symptoms vanished and his visual acuity recovered to the baseline level. The final diagnosis was PRES secondary to systemic hypertension. A CT scan and MRI acquired one week and 15 months later did not show any abnormalities other than those the patient had previous to this episode.

DISCUSSION

PRES is a rare manifestation of hypertension that requires proper diagnosis and management to avoid irreversible brain damage(1). The syndrome is also known as hypertensive encephalopathy and posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome(2,3).

The most common cause of PRES is an abrupt elevation of blood pressure in an otherwise chronically hypertensive patient. This was the case for our patient, who suffered from systemic hypertension that was poorly controlled and then presented with a sudden increase in blood pressure. PRES may also occur after a moderate elevation of systemic blood pressure(3). Other concurrent conditions may predispose patients with elevated blood pressure to this syndrome, including chronic renal parenchymal disease, acute glomerulonephritis, renovascular hypertension, withdrawal from hypertensive agents, encephalitis, meningitis, pheochromocytoma, sympathomimetic agents, lysergic acid diethylamide), eclampsia and preeclampsia, head trauma, collagen vascular disease, autonomic hyperactivity, vasculitis, the ingestion of tyramine-containing foods or tricyclic antidepressants in combination with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and immunosuppressive drugs. We had no evidence of any of these circumstances being present in our patient. The exact mechanism by which PRES occurs is not known with certainty, but recent evidence points to vasogenic edema from a loss of autoregulation in cerebral blood vessels(4).

Visual disturbances are common in PRES, even in the absence of funduscopic abnormalities(5). In our case, the eye fundus examination was normal, indicating that the loss of vision must have been caused by changes somewhere else in the visual pathway. The presence of cortical visual symptoms remains a helpful diagnostic feature indicating occipital lobe involvement. Retinal or optic disc ischemia and papilledema have been implicated when patients have visual complaints(6), but occipital lobe involvement must be considered when the fundi appear normal or there are occasional visuospatial or speech disturbances(5). Typical visual symptoms range from a nonspecific blurriness with normal visual acuity to color-blindness, visual field defects, and even complete blindness. Visual hallucinations, the impairment of facial recognition (prosopagnosia), parietal lobe dysfunction with inappropriate behavior, the denial of blindness (Anton’s syndrome), and blindness with intact pupillary light reflex may simulate drug ingestion or withdrawal, complex migraine, or even a psychiatric illness. Isolated cortical blindness, as occurred in our patient, and occipital lobe seizures as a manifestation of hypertensive encephalopathy, have also been reported(7).

Typical imaging features of PRES include hypodense regions within the posterior white matter regions on unenhanced CT scans and areas of hyperintense signal on T2-weighted MRI images. Diffusion-weighted MRI and quantification of the apparent diffusion coefficient usually reveal vasogenic edema in the parieto-occipital regions of both cerebral hemispheres. The subcortical white matter is always affected and the cortex is often involved. The edema is usually asymmetric, but almost always bilateral(4). Lesions are not enhanced after the administration of contrast material. In our case, MRI revealed a hyperintense lesion in the left cerebellar hemisphere with vasogenic edema in the occipital regions.

Once a patient is diagnosed with PRES, action must be taken immediately to lower the blood pressure, and the administration of intravenous antihypertensive agents is sometimes required. In our case, we achieved successful blood pressure management with oral medication alone. Two days after starting oral antihypertensive treatment, the neurologic signs and symptoms disappeared and the patient’s visual function recovered. A similar outcome was reported in a series of 15 patients with findings indicating posterior leukoencephalopathy, and the condition was therefore termed reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome(8). Because patients with PRES may initially present with only subtle symptoms such as blurred vision, awareness of this disorder may help to reach a prompt diagnosis and instigate proper management to achieve a full recovery within a few days(1).

Early recognition of this condition and the prompt control of blood pressure are essential because they can reverse the syndrome, which may otherwise result in permanent brain damage.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin