INTRODUCTION

Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema (PCME), or Irvine-Gass syndrome, is a common complication following cataract surgery(1). It was first described in 1953 by Irvine, and in 1966, Gass and Norton published an angiographic study of its characteristics(1,2). The incidence of clinical (symptomatic) PCME has been greatly reduced because of its advances in surgical techniques (approximately 0.1%-2.35%), and most cases of PCME have spontaneous resolution(2). Majority of patients remain asymptomatic without active inflammation on fundus examination and optical coherence tomography (OCT)(3). However, subclinical PCME is detected in almost 30% of patients with postsurgical angiography and a further 11%-41% patients with OCT(4).

The pathogenesis of PCME remains obscure. Most investigators agree that inflammation is the main etiologic factor in the development of PCME(5). Inflammatory mediators disrupt the blood-aqueous barrier (BAB) and blood-retinal barrier (BRB), leading to an amplification of retinal permeability and the development of PCME(2,5).

No recent significant studies have been conducted to establish the best therapeutic options for treating this disorder(4). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids represent the most common first-line treatments(4,6). Antiangiogenic therapy, subcutaneous injections of interferon α2a, hyperbaric therapy, and vitrectomy are also therapeutic options(4,5). The dexamethasone implant (DEX implant; Ozurdex; Allergan, USA) is a 0.7 mg biodegradable intravitreal implant that delivers dexamethasone into the vitreous and retina. The drug acts on all inflammatory mediators and has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of macular edema (ME) secondary to retinal vein occlusion (RVO) and for non-infectious posterior uveitis(4). The DEX implant has also been indicated for the treatment of diabetic ME in patients who are pseudophakic or are phakic and scheduled for cataract surgery(4).

In this study, we describe a case series of six patients who were previously diagnosed with PCME and treated with DEX implants.

CASE REPORT

This is a retrospective small case series of six patients who were diagnosed with PCME and treated with DEX implants at the Centro Brasileiro de Cirurgia de Olhos (Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil) and Centro Brasileiro da Visão (Brasília, Distrito Federal, Brazil) between 2013 and 2015. Spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT) was performed with a Spectralis instrument (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) during pre- and post-procedure visits to evaluate macular status (Table 1). The first-line approach in all patients was a topical combination of NSAIDs and corticosteroids for a course of 3 months, what did not result in the clinical resolution of the described cases. Mild glaucoma had been previously diagnosed in two of the patients (Figures 1, 2, and 3). The patients ranged in age from 64 to 74 years (median: 69.75). Three of the patients were men (50.0%). The follow-up period after the procedure ranged from 48 to 201 days. The initial central retinal thickness (CRT) on SD-OCT ranged from 406 to 773 µm (median 542.5), and the final CRT ranged from 218 to 288 µm (median: 219.5). No patient presented significant changes in intraocular pressure during the follow-up period.

Table 1 Patient demographics and treatment history

| Patient | Age (years) |

Gender | Eye | Follow-up after Ozurdex® (days) |

Initial SD-OCT (CRT) |

Final SD-OCT (CRT) |

Initial BCVA (Snellen) |

Final BCVA (Snellen) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | M | OS | 91 | 496 μm | 252 μm | 20/200 | 20/30 |

| 2 | 68 | F | OD | 64 | 529 μm | 227 μm | 20/200 | 20/50 |

| 3 | 69 | M | OD | 195 | 406 μm | 218 μm | 20/80 | 20/30 |

| 4 | 74 | F | OS | 80 | 556 μm | 216 μm | 20/60 | 20/30 |

| 5 | 70 | M | OS | 48 | 773 μm | 221 μm | 20/50 | 20/30 |

| 6 | 74 | F | OS | 201 | 556 μm | 288 μm | 20/60 | 20/30 |

SD-OCT= spectral domain optical coherence tomography; BCVA= best-corrected visual acuity; CRT= central retinal thickness.

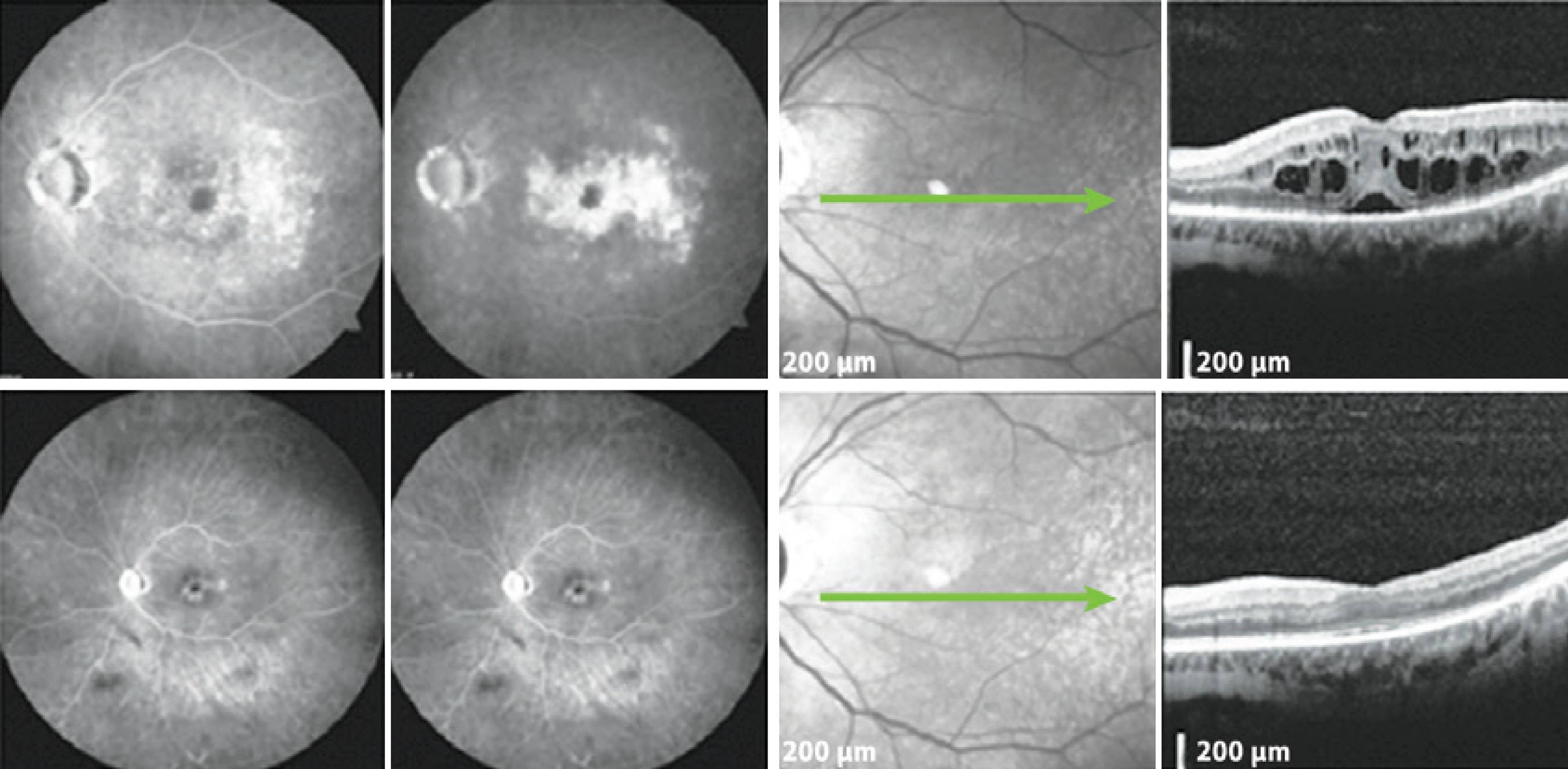

Figure 1 A patient with mild glaucoma and PCME following cataract surgery. Top: FA demonstrates hyperfluorescence with a petaloid aspect in the late frames, and the SD-OCT displays cystic abnormalities, as well as subretinal fluid. Bottom: The patient returned with significantly reduced ME in the SD-OCT. PCME= pseudophakic cystoid macular edema; SD-OCT= spectral domain optical coherence tomography; ME= macular edema; FA= fluorescein angiogram.

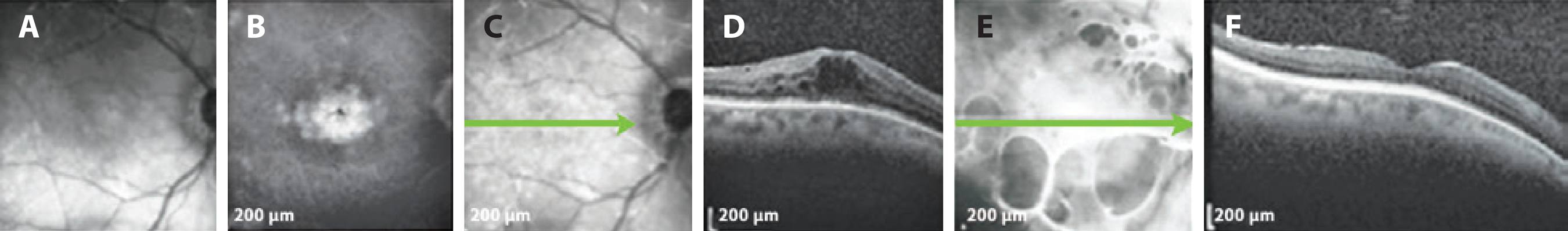

Figure 2 The patient underwent cataract surgery 10 years ago in the OD. Top: FA and SD-OCT before DEX implantation. Bottom: Six months after DEX implantation, late frame FA and SD-OCT showed a reduction of the central retinal thickness of 302 μm. SD-OCT= spectral domain optical coherence tomography; DEX= dexamethasone; FA= fluorescein angiogram.

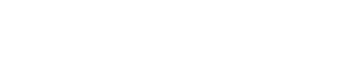

Figure 3 Patient with mild glaucoma under timolol 0.5% BID. A) Infrared photograph. B) Petaloid aspect in central macula displayed in FA of OD. C) SD-OCT demonstrating ME before DEX implantation. D) SD-OCT 195 days after the procedure, with no signs of ME. SD-OCT= spectral domain optical coherence tomography; ME= macular edema; DEX= dexamethasone; FA= fluorescein angiogram; BID= twice daily.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis of PCME remains unclear, but it is generally agreed that inflammation plays a major role in its development(2,4,5,7). Breakdown of the BAB and BRB may be associated with diabetes and glaucoma(2). Patients with diabetes, particularly those with diabetic retinopathy, are at an increased risk of developing PCME(8). In general, cataract surgery results in intraocular inflammation produced by inflammatory mediators that cause increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which potently induces increased permeability of the perifoveal capillary net and breakdown of the BRB(5). However, to date, no studies have shown increased ocular VEGF levels in patients with PCME in the absence of ischemic ocular disease(2).

The DEX implant has been approved by the US FDA for the treatment of ME secondary to RVO, for non-infectious posterior uveitis and for the treatment of diabetic ME in patients who are pseudophakic or are phakic and scheduled for cataract surgery(4).

Dexamethasone has a six-fold more potent anti-inflammatory profile than triamcinolone acetonide(8). A phase II study on the dexamethasone drug delivery system conducted a subgroup analysis that included patients with PCME and patients with uveitis(4,9). A visual gain of at least 15 ETDRS letters was reported at the 90-day follow-up in 53.8% of the patients who were treated with 0.7 mg intravitreal dexamethasone implants(9). In the EPISODIC study, cases of ocular hypertension were reported but were controlled with pressure-lowering medications. No filtering surgery was required(4). In our group of patients, including two with previously diagnosed glaucoma, there was no need to change their current therapies.

In conclusion, when considering the relationship between inflammation and the development of PCME, it is reasonable to hypothesize that DEX implants may offer a promising treatment option for patients who develop PCME following cataract surgery. Controlled studies with larger sample sizes should be performed to confirm these preliminary findings.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin