INTRODUCTION

Cataract is a common complication of uveitis, and may result from chronic intraocular inflammation because of the use of corticosteroids. Cataracts are difficult to manage, particularly in children; therefore, choice of surgery should be based on the assessment of quality of vision; preoperative control of inflammation; and intraoperative issues such as poor visibility due to band keratopathy, myosis, synechiae, pupillary membranes, and bleeding(1). Postoperative follow-up may also be challenging, and the frequency of complications may be higher than usual(1-6).

However, diagnostic techniques and medical and surgical treatments have greatly improved, increasing surgical indications. Furthermore, cataracts in children may be amblyogenic, which does not facilitate diagnosis and treatment of posterior segment complications(1-6).

CASE REPORTS

We report the cases of three female children, two of whom were aged 6 years and one was aged 11 years. All girls reported bilateral low visual acuity, ranging from the ability to count fingers at a distance of 3 m to light perception; two of the girls were diagnosed with bilateral chronic diffuse uveitis and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease and the third girl was diagnosed with sympathetic ophthalmia (SO).

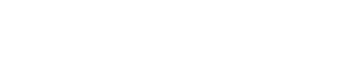

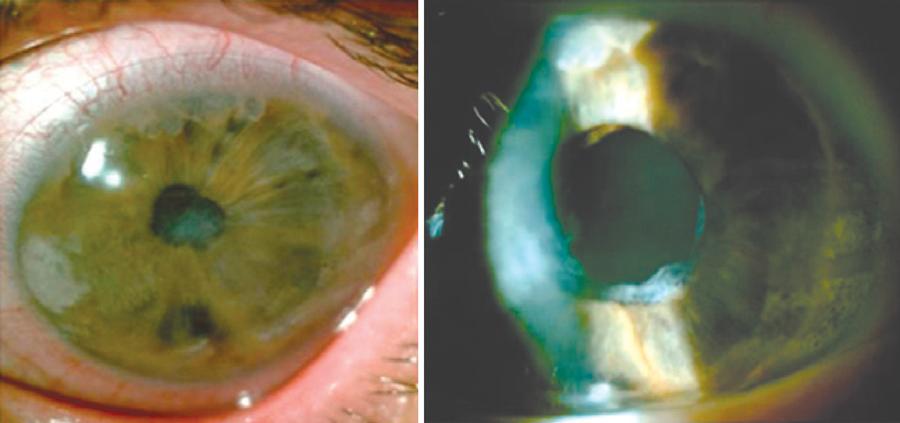

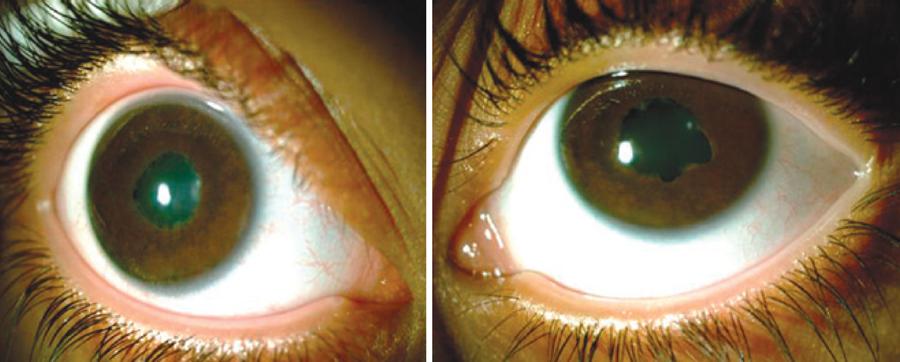

Biomicroscopy showed band keratopathy, granulomatous keratic precipitates, posterior synechiae, and opaque pupillary membranes, which bilaterally obstructed the lens evaluation in two girls, and also in one eye of the third girl who had undergone penetrating keratoplasty with graft failure in the fellow eye.

Intraocular pressure levels were within normal limits. Fundus evaluation was impossible because of media opacity. Ultrasound revealed that the posterior segments were unchanged. After controlling inflammation with topical and systemic steroids, several experienced ophthalmologists recommended phacoemulsification without intraocular lens implantation in the left eye of each patient.

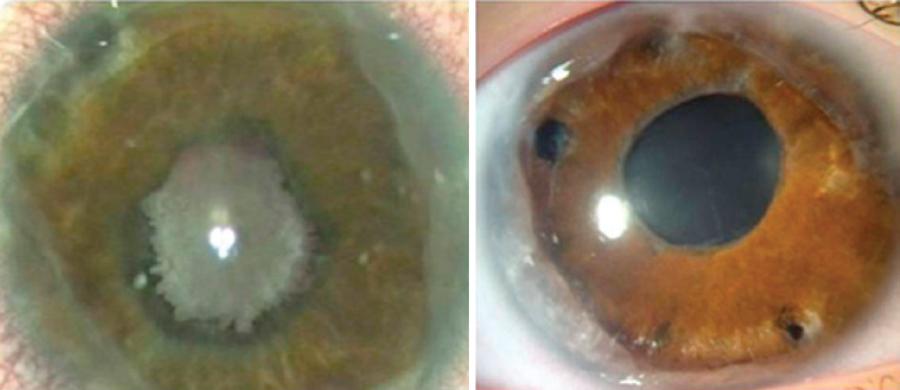

Intraoperatively, after lysing the posterior synechiae and excising the epilens membrane, the crystalline lenses were observed to be transparent, and the red reflex was present; therefore, phacoemulsification was not performed. Fundoscopy, which was possible postoperatively, revealed VKH disease and SO. The three patients recovered well postoperatively, with mild inflammatory reactions, and achieved best-corrected visual acuities ranging from 20/30 to 20/100. The three patients did not develop cataract during the postoperative period, which ranged from 1 to 7 years (Figures 1, 2, and 3).

DISCUSSION

Here we report three girls with uveitis and suspected cataract, whose lenses appeared transparent upon membranectomy. Phacoemulsification was aborted in all three cases.

The three patients had surgical indications for phacoemulsification, and despite the assumption of cataract, the girls actually had epilens membranes and transparent lenses.

If the patients had not been carefully evaluated intraoperatively with delicate removal of the inflamed epilens membranes, the crystalline lenses could have been removed, inadvertently risking future vision and increasing the possibility of the development of secondary glaucoma and other diseases(5,6).

It is important to emphasize the risk of rupture of the anterior capsule during the release of the prepupillary membrane and synechiolysis. Therefore, surgeons need to have sufficient skill and practice to perform these very delicate maneuvers to avoid complications.

Differential diagnosis of leukocoria in children with uveitis should include epilens membranes. Patients who develop uveitis with a pupillary membrane as a complication should be carefully evaluated. Intraoperatively, if the lens is found to be transparent, a less aggressive therapy should be instituted. Ophthalmic surgeons should consider removal of epilens membranes as a surgical option.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin