INTRODUCTION

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a complex ocular disease of multifactorial etiology with demographic, environmental, and genetic risk factors(1). AMD is the leading cause of irreversible blindness among elderly individuals in the developed world(2).

AMD can be classified into two subtypes: non-exudative (dry AMD) and exudative (wet or neovascular AMD). Exudative AMD is characterized by geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularization and involves the abnormal growth of neovessels from the choriocapillaris layer through breaks in the Bruch's membrane and retinal pigment epithelium(3). Fenestrated neovessels allow the extravasation of fluids, lipids, and blood below and within the retina leading to the deterioration of central vision(4,5). Clinically, AMD leads to clinically important functional visual loss and reduced quality of life, which are often underestimated(6). Risk factors for AMD include age, smoking, systemic arterial hypertension (SAH), high serum cholesterol, and substantial alcohol consumption. In addition, studies have provided evidence indicating the important role of genetic factors in the physiopathology of AMD(7). Recently, a number of studies have evaluated the relationship between vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) polymorphisms and AMD genetic susceptibility variants(4).

The VEGF glycopeptide family includes the subgroups VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, VEGF-E, and placental growth factor (PGF). These factors are critical for the formation and maintenance of normal vascular function through direct effects on the proliferation, survival, and migration of endothelial cells. Notably, VEGF-A is considered the predominant mediator of angiogenesis.

The human VEGF-A gene is located on chromosomal region 6p21.3 and contains eight exons and seven introns. VEGF-A pre-mRNA undergoes alternative splicing producing protein isoforms of 121, 145, 165, 183, 189, and 206 amino acids. The expression of the VEGF165 isoform has predominantly been reported in the human eye(6).

A number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in the gene encoding VEGF-A and are thought to have functional activity, namely alteration of gene expression and protein production, which may underlie their identification as risk factors for AMD(8).

In the present study, we investigated a SNP consisting of replacement of a cytosine by a thymine at position 936 (C936T-rs3025039) within the untranslated region 3'UTR of the VEGF gene. This polymorphism has been shown to modulate VEGF-A expression(8); however, there have been conflicting results from diverse ethnic populations regarding its association with AMD(4).

Accordingly, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the associations between the VEGF-C936T polymorphism and serum VEGF levels, lifestyle, and demographic parameters in patients with AMD.

METHODS

A total of 183 individuals were selected regardless of sex or ethnic group and divided into two groups. The Study Group (SG) comprised of 88 patients with a diagnosis of AMD (exudative forms) receiving clinical and pharmacological treatment (mean age, 72 years; range, 51 years-89 years old; 50% male). All patients underwent visual acuity testing and complete ophthalmological examination, including angiofluoresceinography and optical coherence tomography. The Control Group (CG) comprised 95 individuals undergoing routine preoperative testing prior to cataract surgery with no clinical or angiographic signs of the disease (mean age, 59 years old; range, 50 years-81 years; 57% male).

All subjects were assessed by an ophthalmologist at a private clinic and at the Ophthalmology Outpatient Clinic of the University Hospital of the Medical School of Ribeirão Preto (FMRP-USP) between January 2013 and October 2013. Subjects younger than 50 years of age or with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus were excluded. Patients with ocular media opacity preventing retinal evaluation were also excluded. All participants completed a questionnaire regarding lifestyle and medical history. Regarding smoking habits, both former and current smokers were evaluated; however, pack-year histories were not recorded. Individuals with any history of alcohol consumption, whether casual or heavy, were considered alcohol consumers.

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood (5 mL) collected in tubes containing EDTA using the salting-out technique(9). Polymorphic fragments were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Mastercycler, Eppendorf) using 0.5 mL of each deoxynucleotide (0.8 mM), 2.5 mL of 10× PCR buffer, 2.5 mL of 10% dimethylsulfoxide, 2.5 mL of each primer (2.5 mM), 0.2 mL of Taq polymerase (5 U/mL), 11 mL of Milli Q water, and 2 mL of diluted genomic DNA (0.2 µg). The VEGF-C936T (rs3025039) polymorphism was analyzed by PCR using the following primer sequences designed to produce a 198 base pair (bp) fragment: P1, 5'-AAGGAAGAGGAGACTCTGCCG-3' and P2, 5'-TATGTGGGTGGGTGTGTCTACAGG-3'(10). Genomic DNA (50 ng) amplification (ESCO Thermocycler) was performed over 30 cycles (95ºC for 60 s, 59ºC for 60 s, and 72ºC for 60 s) followed by a final extension step of 10 min at 72ºC. For restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, amplification products were incubated with the NlaIII restriction enzyme and were assessed by 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis at 90 V for 1 h and 30 min, stained with GelRed® (Uniscience), and visualized under ultraviolet (UV) light.

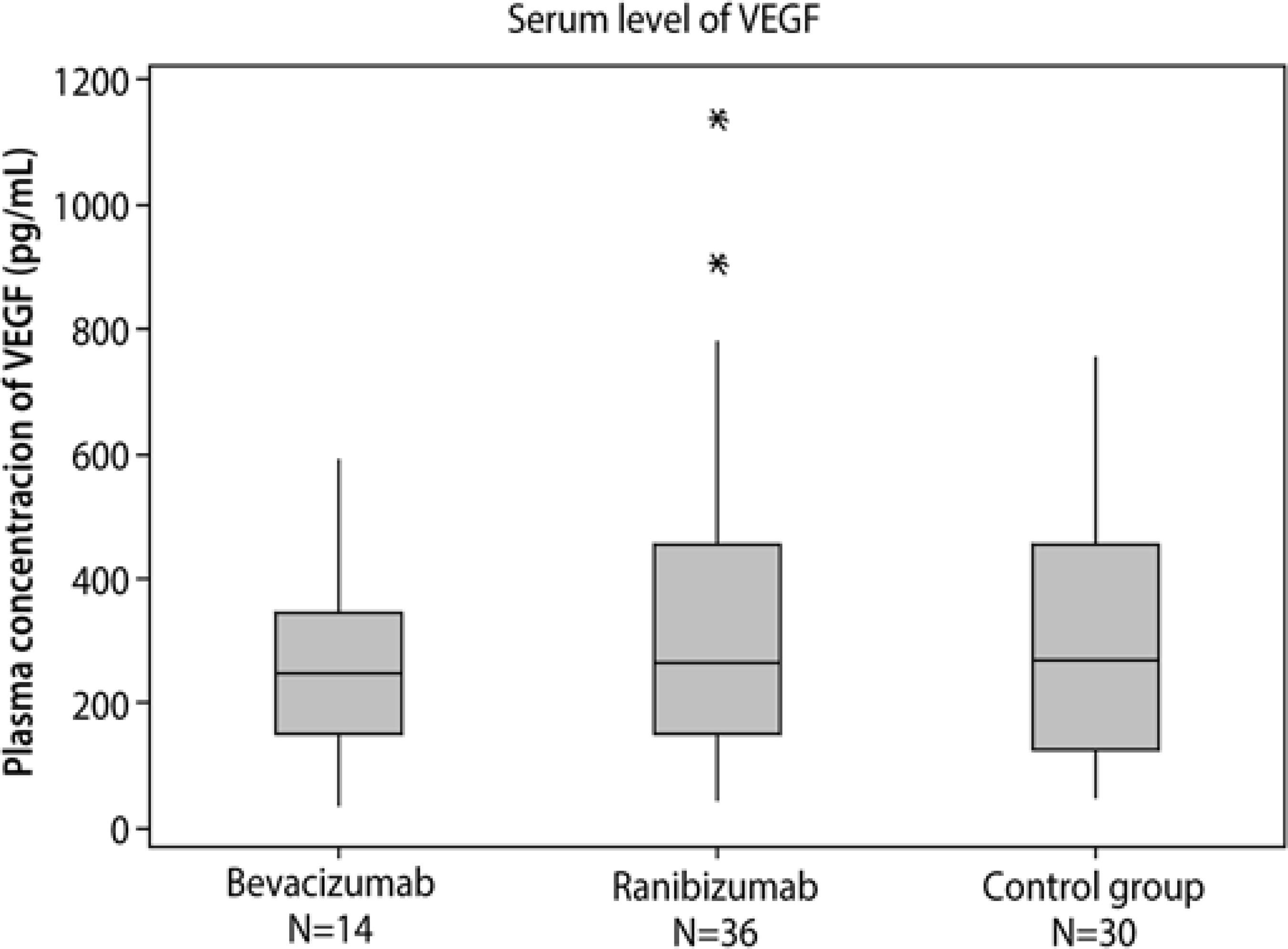

Serum VEGF concentrations were measured in 50 of the 88 (57%) patients and 30 of the 95 (31%) controls using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Quantkine R&D Systems Inc., USA), with 220 pg/mL used as the reference value, according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems). Serum VEGF concentrations in the SGwere analyzed with consideration of the effects of ranibizumab and bevacizumab treatment. Of the 50 patients in the SG with serum VEGF level measurements, 14 (28%) and 36 (72%) patients received intravitreal injection of bevacizumab and ranibizumab, respectively. The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical School of São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil. All participants were informed about the study and provided signed informed consent documents prior to enrolment into the present study.

Data were statistically analyzed using Fisher´s exact test, the chi-square test, or the Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate using MiniTab14and GraphPad3 software. Data are presented as box-plots with median and quartile values. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The homozygous wild-type genotype (CC) was predominant in both the SG and CG (78% and 80%, respectively; P=0.934), with a similar result observed for the frequency of the C allele (SG, 0.89; CG, 0.90; P=0.938; Table 1). Regarding lifestyle, a higher prevalence of smokers was observed in the SG (44.3%) compared to the CG (25.3%; P=0.010). A higher prevalence of alcohol consumption was observed in the SG (23%) compared to the CG (18%), although the difference between groups was not found to be statistically significant (P=0.529). The prevalence of comorbidities was similar between groups (P>0.05), except for a higher frequency of SAH among the SG (65.9%) compared to the CG (48.4%; P=0.025; Table 1).

Table 1 Allele and genotype frequencies of VEGF-C936T polymorphism and demographics of patients with age-related macular degeneration (study group) and individuals without AMD (control group)

| Characteristic | Study group (N=88) | Control group (N=95) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF-C936T | N | % | N | % | P -value | Odds ratio | IC | |

| Genotype | ||||||||

| CC | 69 | 78.4 | 76 | 80.00 | ||||

| CT | 19 | 21.6 | 19 | 20.00 | 0.934 | 1.10 | 0.53-2.25 | |

| TT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Total | 88 | 100.0 | 95 | 100.00 | ||||

| Allele | Absolute frequency | Absolute frequency | ||||||

| C | 157 | 0.89 | 171 | 0.90 | ||||

| T | 19 | 0.11 | 19 | 0.10 | 0.938 | 1.08 | 0.55-2.13 | |

| Total | 176 | 1.00 | 190 | 1.00 | ||||

| Lifestyle | ||||||||

| Smoking | 39 | 24 | 25.30 | 0.010 | 2.35 | 1.26-4.40 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 20 | 17 | 17.90 | 0.529 | ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 58 | 46 | 48.40 | 0.025 | 2.05 | 1.13-3.74 | ||

| Dyslipidemias | 20 | 28 | 29.50 | 0.385 | ||||

*= P<0.05 according to Fisher's exact and Chi-square; N= number of individuais; VEGF= vascular endothelial growth factor; IC= confidence interval.

Serum VEG levels, measured in 57% of the SG and 31% of the CG, were comparable between patients with AMD (treated with bevacizumab or ranibizumab) and controls (P=0.903; Figure 1). However, a large degree of heterogeneity in serum VEGF levels was observed between groups with 25% of patients with AMD treated with ranibizumab having serum VEGF levels greater than 451.5 pg/mL and as high as 1,135.5 pg/mL. These levels were comparable to the control group (mean, 454.6 pg/mL), whereas the corresponding value for patients with AMD treated with bevacizumab was 343.3 pg/mL (Figure 1). Additionally, no associations were observed between VEGF-C936T polymorphism and serum VEGF levels, lifestyle, or comorbidities either within or between groups (P>0.05; Table 2).

N= number of individuals; *= outlier.

Figure 1 Box-plot showing median values and quartiles values for serum VEGF levels. VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor. Bevacizumab: Q1= 147.8; median= 245.1; Q3= 343.3; IQ range= 195.4. Ranibizumab: Q1= 149.7; median= 263.3; Q3= 451.5; IQ range= 301.8. Control group: Q1= 125.4; median= 267.8; Q3= 454.6; IQ range= 329.2. P=0.903 by Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table 2 Associations between VEGF-C936T and lifestyle, comorbidities, and serum VEGF levels in patients with AMD (study group) and individuals without AMD (control group)

| Study group | Control group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Genotype | Smoking | Non-smoking | Smoking | Non-smoking | |||||

| -T | 8 | 20.5 | 11 | 22.4 | 6 | 25.0 | 13 | 18.3 | |

| CC | 31 | 79.5 | 38 | 77.6 | 18 | 75.0 | 58 | 81.7 | |

| Total | 39 | 100.0 | 49 | 100.0 | 24 | 100.0 | 71 | 100.0 | |

| Alcohol | Non-alcohol | Alcohol | Non-alcohol | ||||||

| -T | 2 | 10.0 | 17 | 25.0 | 3 | 17.6 | 16 | 20.5 | |

| CC | 18 | 90.0 | 51 | 75.0 | 14 | 82.4 | 62 | 79.5 | |

| Total | 20 | 100.0 | 68 | 100.0 | 17 | 100.0 | 78 | 100.0 | |

| Hypertension | Non-hypertension | Hypertension | Non-hypertension | ||||||

| -T | 12 | 20.7 | 7 | 23.3 | 10 | 21.7 | 9 | 18.4 | |

| CC | 46 | 79.3 | 23 | 76.7 | 36 | 78.3 | 40 | 81.6 | |

| Total | 58 | 100.0 | 30 | 100.0 | 46 | 100.0 | 49 | 100.0 | |

| Dyslipidemia | Non-dyslipidemia | Dyslipidemia | Non-dyslipidemia | ||||||

| -T | 5 | 25 | 14 | 20.6 | 4 | 14.3 | 15 | 22.4 | |

| CC | 15 | 75 | 54 | 79.4 | 24 | 85.7 | 52 | 77.6 | |

| Total | 20 | 100 | 68 | 100 | 28 | 100.0 | 67 | 100.0 | |

| VEGF pg/mL | >220 | ≤220 | >220 | ≤220 | |||||

| -T | 6 | 21.4 | 5 | 22.7 | 2 | 12.5 | 1 | 7.14 | |

| CC | 22 | 78.6 | 17 | 77.3 | 14 | 87.5 | 13 | 92.86 | |

| Total | 28 | 100 | 22 | 100 | 16 | 100.0 | 14 | 100.0 | |

*= P>0.05 for comparison between groups and within groups by Fisher's exact test or Chi-square test; N= number of individuais; VEGF= vascular endothelial growth factor.

DISCUSSION

This present study found no association between VEGF-C936T polymorphism and AMD, corroborating the findings of a previous meta-analysis(11). The VEGF-C936T polymorphism has been evaluated in three previous studies with conflicting results. No association was reported in two of the previous studies in Chinese(12) and Caucasian(13) populations. However, a different study in a Chinese population(14) reported an association between VEGF-C936T polymorphism and AMD. These results may be explained by the close genetic linkage (D'=0.99) between the VEGF-C936T polymorphism and a different single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the gene complement factor H (CFH - rs1061170) that has previously been shown to be associated with AMD(15). The frequencies of the VEGF-C936T SNP and alleles (Table 2) were not found to differ between both groups, corroborating previous data obtained for Caucasian (0.80)(13) and Chinese populations (0.85)(12). However, a lower frequency of the 936T allele (0.10) was observed compared to previous studies of Austrian (0.16)(16) and Chinese (0.19) populations(17). However, the Brazilian population is a result of interracial mixing of European, Amerindian, and African populations(18) with each group representing a substantial genetic contribution. Therefore, any evaluation of the contribution of ethnicity to the association between genotype and AMD is challenging in this population. Consequently, more detailed and comprehensive studies are required in various geographical regions of Brazil.

Regarding lifestyle and comorbidities, an association was observed between smoking and AMD, as reported in previous studies(3,7). Cigarette smoking is directly associated with increased risk of AMD, typically two-fold higher, when comparing current smokers with individuals who have never smoked(19). Toxic cigarette substances, such as nicotine and cotinine, found in the plasma of smokers promote the formation of arachidonic acid, a precursor of important inflammatory mediators including prostaglandins and leukotrienes(20). Further, cigarettes contain high concentrations of pro-oxidant substances, such as hydroquinone, which may contribute to an increased risk of developing AMD(21).

The present study demonstrated an association between SAH and AMD, corroborating the findings of a previous meta-analysis by Chakravarthy et al.(22) that demonstrated SAH as a risk factor for AMD with a moderate strength of association.

Serum VEGF levels, assessed in 57% of patients in the SG and in 31% of subjects on the CG, were comparable between groups, in agreement with a previous study in a European population(23). However, these findings are in contrast with a previous report in an Asian population(24). This discrepancy may be related to differing study populations or use of analytic techniques.

Various therapeutic procedures have been utilized in attempts to delay the progression of visual impairment caused by AMD, althoughwith limited success. Today, a number of pharmacological agents have demonstrated more promising results in inhibiting the effects of VEGF(25). The intravitreal administration of bevacizumab, a human class IgC1 monoclonal antibody against VEGF, for the treatment of AMD may eventually be absorbed into the blood circulation leading to reductions in serum VEGF levels(26). In this study, all patients with AMD were already being treated with intravitreal injections of bevacizumab or ranibizumab, which may explain the similar VEGF serum levels observed between the SG and the CG.

Detailed evaluation of the medical history of individual patients, including the number of anti-VEGF applications and the interval between blood sampling and the last application of anti-VEGF agents (data not available at the time of the present study), may have further clarified the efficacy of pharmacological treatment with antiangiogenics on maintaining VEGF serum levels within reference limits.

CONCLUSION

In the present study of Brazilian patients, the VEGF-C936T polymorphism was not found to be associated with AMD. Similar VEGF levels were observed between patients with AMD and controls, possibly indicating reduced systemic VEGF levels and the success of pharmacological therapy. The results of this study indicate smoking and SAH may be independent risk factors for the development of AMD.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin