INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (IPCV) is a vascular malformation of the choroid, comprising a network of branching vessels of varying sizes that produce aneurysmal-like enlargements. This disease is generally observed in the peripapillary area, and less commonly as an isolated macular lesion(1).

Frequently, the IPCV vascular network is associated with multiple episodic serosanguineous detachments of the retinal pigment epithelium and neurosensory retina, which occasionally lead to sub-retinal(1-3)and on rare occasions vitreous(4) hemorrhage. When the vascular network is beneath the atrophied pigment epithelium, a clinical diagnosis of IPCV is recommended if reddish orange, spheroidal, or polyp-like structures are observed. Nevertheless, in the majority of cases these lesions are not clearly visible, and indocyanine green angiography (ICG) is required for diagnosis(2,3).

ICG images illustrate two components of vascular abnormalities in the choroidal circulation: 1) a branching vascular network and 2) aneurysmal dilations at the end of the vascular network branch. These dilations can also be divided into two patterns: 1) large solitary round aneurysmal dilations, which usually present a stable and favorable clinical course and 2) a collection of small aneurysmal dilations resembling a cluster of grapes, which tend to bleed or leak and cause severe visual loss(5).

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is another exam used to characterize the IPCV lesion(6), and is used mainly when retinal pigment epithelium and serous retinal detachment are suspected(7). However, this approach has not yet been described in peripheral IPCV.

A major problem with the diagnosis of peripheral IPCV is that it masquerades as several mass lesions or tumors, such as acquired vasoproliferative disease, metastatic lesions to the choroid, choroidal melanoma, or choroidal osteoma. The goal of this case report was to elucidate the diagnosis of a temporal lesion that mimicked a tumor mass, as well as describe the follow-up approach for assessing treatment need if the patient’s vision becomes threatened or compromised.

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old asymptomatic African American woman was referred to us with a suspected diagnosis of vascular choroidal tumor and choroidal capillary hemangioma. The patient had lived with systemic arterial hypertension for 18 years, which was treated with enalapril maleate® at 25 mg per day, and diabetes mellitus for 1 year, which was treated with metformin at 850 mg twice per day.

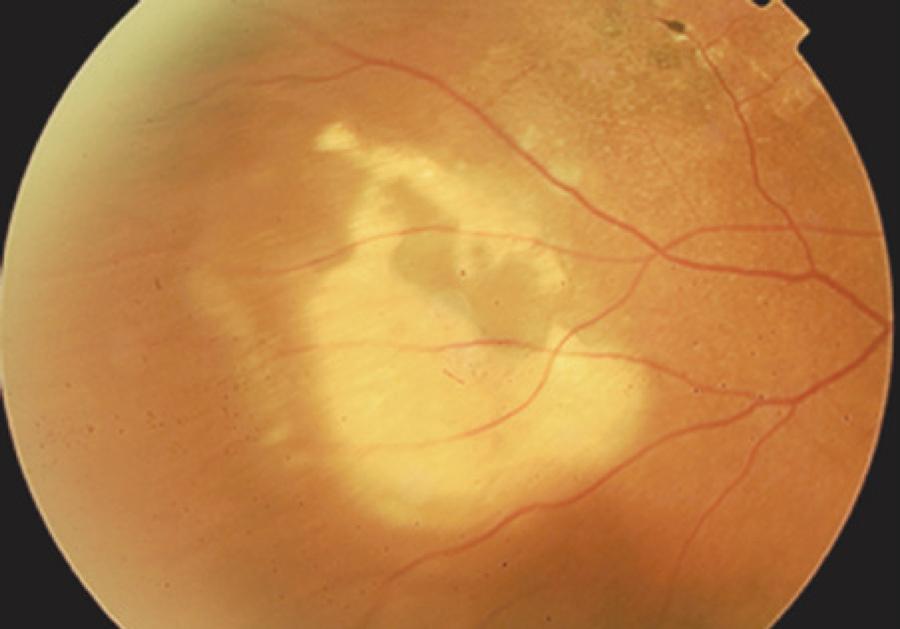

Upon initial examination, the patient’s visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes, she had no afferent pupillary defects, and had normal intraocular pressure measurements. Slit-lamp examination revealed only pinguecula on the right eye (OD) and asteroid hyalosis in the left eye (OS). Upon fundus examination of OD, there was an elevated lesion in the middle periphery of the inferior temporal region adjacent to multiple areas of pigment epithelium detachment (PED). In addition, at 2 o'clock in relation to the lesion, a peculiar, smaller elevation resembling a vascular tumor (Figure 1A) was observed.

Figure 1. A) Fundus retinography demonstrating an elevated lesion in the mid-periphery of the inferior temporal vascular arcade, as shown by the long black arrow, and a lesion resembling the vascular tumor at the 2 o'clock position, as shown by the short black arrow. B) Right fundus. A middle phase of the fluorescein angiography showing minimal leakage and pooling. C) Indocyanine green angiogram showing the tubular elements ending in aneurysmal or polypoidal dilatations with little leakage of the dye. In both exams, the lack of fluorescence (i.e., black appearance) was due to major hemorrhagic pigment epithelium detachment.

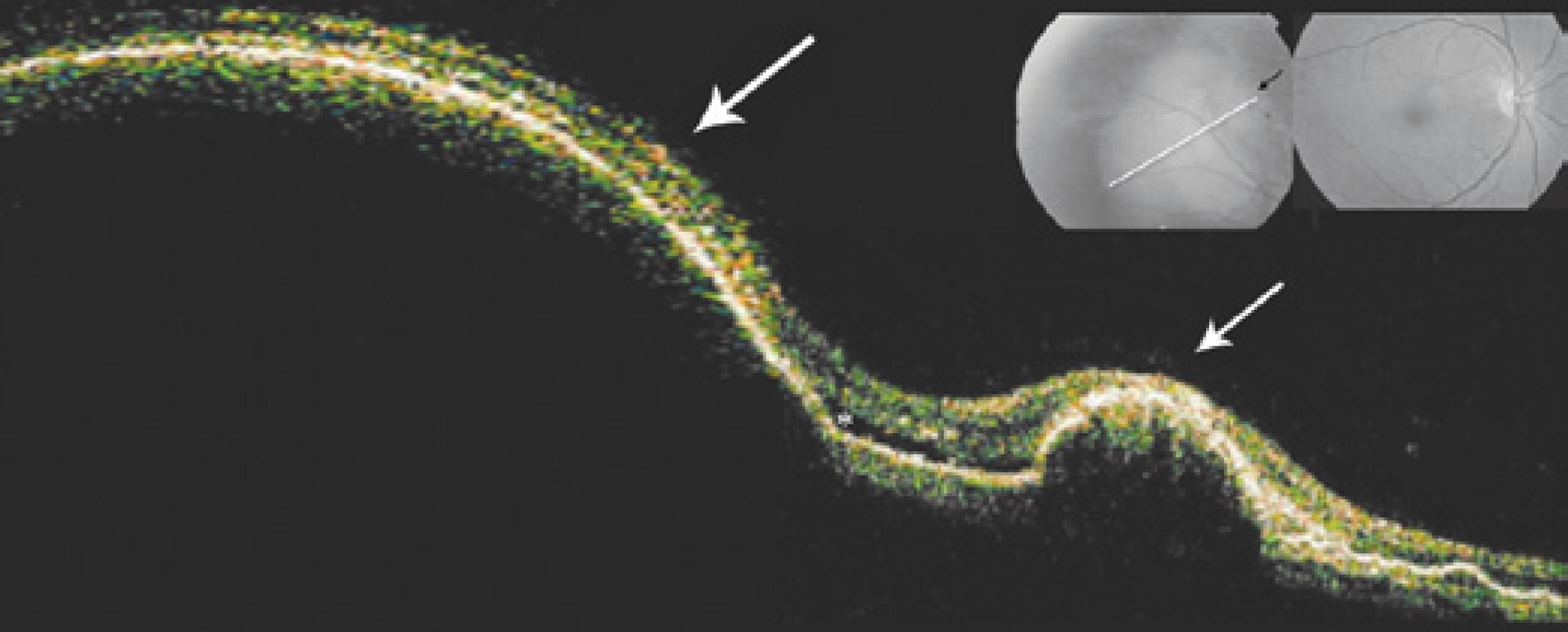

The OCT examination of the major lesion in OD revealed a large PED with adjacent smaller lesions resembling a vascular tumor, and these observations were correlated with retinal serous detachment (Figure 2). Fluorescein angiography of OD showed a patchy area of subretinal staining of undetermined origin, with minimal leakage and a blockage area corresponding to the elevated lesion (Figure 1B). ICG revealed the presence of an inner choroidal vascular abnormality that ended in multiple small, hyperfluorescent polyps with leakage characteristic of IPCV, as well as a permanent blockage area observed during all phases of the angiogram, which corresponded to the major PED (Figure 1C). No macular changes were observed. One year later, there was decreased dimension and discoloration of the lesions, which now resembled a choroidal osteoma (Figure 3). After the initial visit no treatment was administered, because the macula was not threatened.

Figure 2. OCT showing the larger lesion, represented by the long white arrow, and the smaller lesion, represented by the short white arrow, corresponding to hemorrhagic pigment epithelium detachments (PED). Note the presence of serous retinal detachment, as shown by the asterisk, and multiples areas of PED on the right.

DISCUSSION

Recent findings have expanded our knowledge surrounding the nature of the vascular lesions that occur during the course of IPCV(4). The most common region of occurrence is the peripapillary or macular area, and even in these cases the diagnosis is challenging due to variability in disease presentation, as well as the fact that this condition is uncommon and can only be confirmed using ICG(2). Therefore, patients suffering from this disease are almost always initially diagnosed with malignant tumor lesions.

In the first case of peripheral IPCV(9), the patient demonstrated characteristic peripheral subretinal hemorrhage associated with hard exudates, and was free of systemic disorders. Our patient presented a similar lesion location (temporal inferior), but did not show hemorrhage or hard exudates, possibly due to its benign course.

In the case described here, the use of OCT was important, because it permitted the observation of multiple serosanguineous detachments of the retinal pigment epithelium, and neurosensory retina isolated between the two PED that was not threatened. Moreover, the approach enabled the detection of a major lesion that resembled a tumor, but was instead correctly identified as a major PED.

A major strength of this case, which we followed for one year, was that the differential diagnosis performed early after disease onset included vasoproliferative acquired disease, capillary hemangioma, focal posterior scleritis, and primary tumor. However, in the late phase (Figure 3), due to the appearance of discolored lesions likely associated with the absorption of blood, potential diagnoses suggested were metastatic tumors and choroidal osteoma.

Consistent with a previous report(2), ICG was essential in establishing a diagnosis of IPCV in this patient, because it uncovered polypoidal and aneurysmal dilations at the terminals of the branching vascular network(10). The patient presented with a peripheral collection of small aneurysmal dilations, which is a risk factor for bleeding that can lead to vision loss and has a poor prognosis. However, the disease course in this patient has been benign and was appropriately identified within a year.

No treatment was administered to this patient, because there was no subretinal fluid accumulation, hard exudates, or hemorrhage threatening the fovea. This patient is currently under continued observation.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin