INTRODUCTION

Hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of diseases involving weakness and spasticity of the lower extremities combined with additional neurological or non-neurological manifestations(1). There are almost 48 subtypes of HSP; however, only the 2 subtypes involving mutations of SPG11 and SPG15 are associated with Kjellin’s syndrome(1).

The inheritance of Kjellin’s syndrome is autosomal recessive, and the syndrome is characterized by spastic paraplegia, mental retardation, amyotrophy, thin corpus callosum, and macular dystrophy(2). Individuals with this syndrome present with macular changes, most often described as fundus flavimaculatus or Stargardt disease-like, particularly on the basis of fluorescein angiography findings(3).

Here we describe ophthalmological findings in a patient with Kjellin’s syndrome, extending previous reports by demonstrating retinal functional and multimodal retinal imaging studies.

CASE REPORT

A 34-year-old white male was admitted to São Paulo University Hospital in Ribeirão Preto, for investigation of spastic paraparesis. At 20 years of age, he had developed muscle weakness in the lower limbs with difficulty in walking. The symptoms progressed slowly; however, 2 years later he had lost the ability to walk unaided.

Since childhood, he had experienced learning difficulties and mild cognitive impairment combined with hypoacusis. His mother reported that he had recently displayed aggressive behavior. There was no long-term history of visual acuity impairment; however, he reported progressive worsening of vision over the past 2 years Prior to admission, there was no significant family history and the only medication was fluoxetine 20 mg per day.

Neurological examination revealed dysarthria, frontal release signs, preserved perception of touch and pain, spasticity of the lower limbs with a scissors gait, and loss of strength and muscle atrophy in the lower limbs and interosseous muscles of the hands. Laboratory studies revealed negative HIV, VDRL, FTA-abs, HTLV I/II, and hepatitis B and C serology. Vitamin B12 and folic acid levels were within normal limits.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed significant volumetric loss and corpus callosum atrophy. Electroneuromyography showed severe denervation of segmental cranial, cervical, thoracic, and lumbosacral muscles, suggesting diffuse lower motor neuron disease. Audiometry detected profound sensorineural hearing loss.

Ophthalmological evaluation

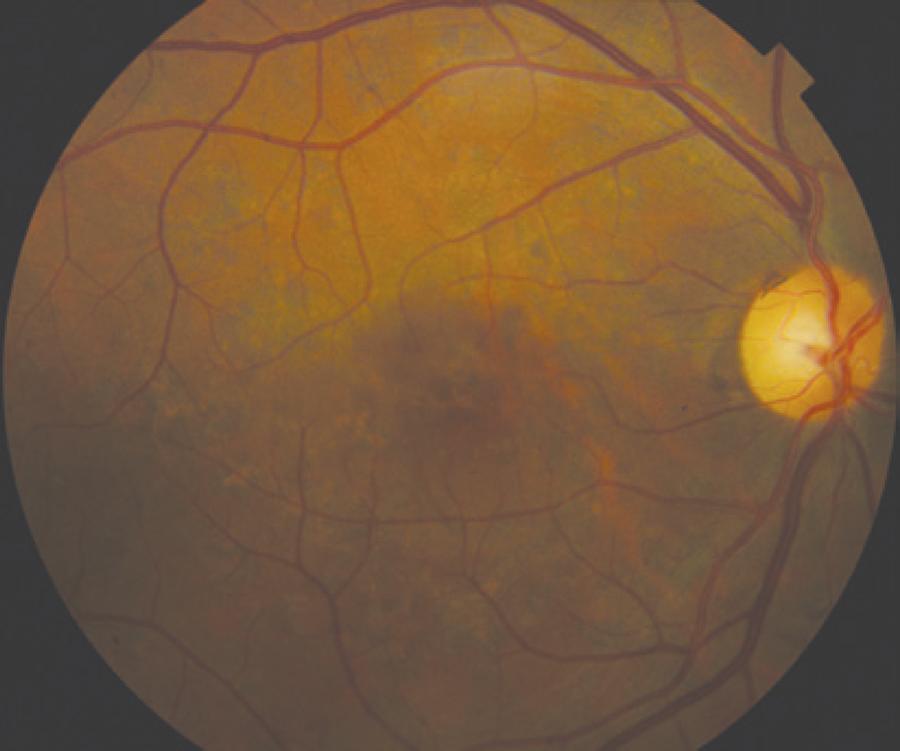

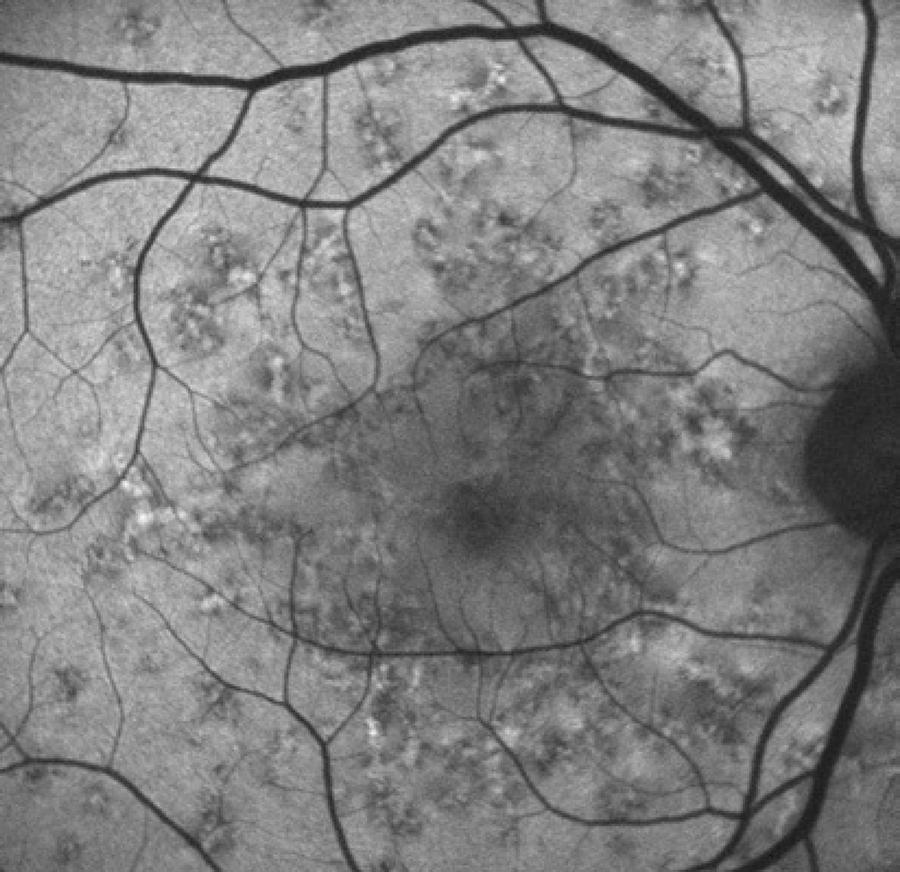

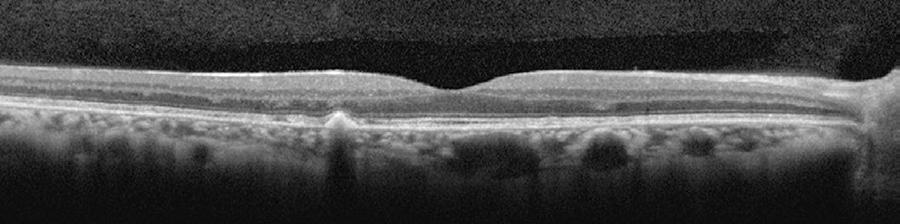

Only mild visual acuity loss was detected, with best-corrected visual acuity of 20/25 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye. Pupillary direct and consensual light reflexes were normal and ocular motility was preserved. Intraocular pressure was within the normal range: 14 mmHg in the right eye and 15 mmHg in the left eye (Goldmann). Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed transparent cornea and lenses with no noteworthy structural changes. The fundus presented multiple round yellowish flecks at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium scattered at the posterior pole. Some of these flecks were elongated and showed partial confluence with neighboring flecks (Figure 1). Imaging was performed with a Spectralis HRA + OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Areas of increased fundus autofluorescence (FA) were noted, with surrounding borders of decreased FA intensity, corresponding to the visible yellowish fundus lesions (Figure 2). Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) showed elevated lesions along the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)/ Bruch complex, preserving the external limiting membrane (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Color fundus photograph showing symmetric multiple uniform round yellowish lesions at the posterior pole.

Figure 2 Fundus autofluorescence showing high levels of autofluorescence in the center of the biomicroscopically visible flecks and surrounding halos with decreased autofluorescence signal.

Figure 3 Spectral domain optical coherence tomography [SD-OCT] showing elevated lesions located along the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)/Bruch complex and preserving the external limiting membrane.

Full field and multifocal electroretinography (ERG and mfERG, respectively) were recorded and stored for offline analysis using an Espion E2 system (Diagnosys LLC, Littleton, MA, USA) in accordance with the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) guidelines. The ERG amplitude and implicit time were within normal limits; however, mfERG (Diagnosys LLC) revealed areas of amplitude reduction. Microperimetry (MAIA; CenterVue, Padova, Italy) showed test points with reduction of sensitivity but fixation was relatively stable.

DISCUSSION

The presented patient shows typical phenotypic traits of Kjellin’s syndrome characterized by absence of the corpus callosum and macular changes. These traits are suggestive of HSP subtypes 11 and 15, known to be associated with deformity of the corpus callosum(1,4-6).

The natural history of macular dystrophy in Kjellin’s syndrome is such that patients rarely complain of low visual acuity unless it is associated with cataract or optic neuropathy(1,3). In this context, microperimetry could be more sensitive to detect functional impairment in Kjellin’s syndrome, because preserved visual acuity is normally found if the fovea is not involved. However, microperimetry findings show a clear distinction in comparison with eccentric and unstable fixation and the loss of sensitivity found in Stargardt disease(7).

As expected, no changes were recorded on ERG, presumably because of the mild and focal retinal impairment typical of Kjellin’s syndrome(8). However, there were obvious changes on mfERG, with areas of reduced amplitude bilaterally(8).

Interestingly, some characteristics of the yellowish-white flecks interspersed with diffuse pigmented lesions found in Kjellin’s syndrome also differ from those found in Stargardt disease and fundus flavimaculatus. In Kjellin’s syndrome, the areas of increased FA are surrounded by halos of decreased FA(9,10).

On SD-OCT, the presence of elevated lesions along the RPE/Bruch complex, corresponding to areas of increased FA without atrophy of the RPE/Bruch complex and the inner and outer segment (IS/OS) layer, also differ from the findings in Stargardt disease and fundus flavimaculatus(9-11).

The diagnosis of macular changes in HSP is important for the genetic evaluation because macular changes indicate association with subtypes 11 and 15. The mutations occur in KIAA 1840 (SPG11) and ZFYVE 26 (SPG15) that encode the proteins spatacsin and spastizin, respectively(1). These proteins are part of the AP5 membrane-trafficking complex and have been identified in animal models of photoreceptor cells(12). This suggests that the retinal changes in Kjellin’s syndrome might be the result of a metabolic defect, causing accumulation of products related to lipofuscin.

In summary, this case represents Kjellin’s syndrome with a complete SPG11 and SPG15 phenotype with macular changes. The ophthalmological changes, particularly at early stages of the disease, may not impair visual acuity but can be detected with microperimetry, careful fundus examination, and autofluorescence and/or SDOCT.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin