Raíra Fortuna Cavaliere Mendes Moraes1; Carolina Pelegrini Barbosa Gracitelli1; Célia Regina Nakanami1; Julia Dutra Rossetto1,2

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2025-0113

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: This study aimed to identify the strategies adopted by Brazilian ophthalmologists to control myopia in clinical practice.

METHODS: This was a prospective cross-sectional study. Data were collected using an online questionnaire.

RESULTS: Responses from 148 participants were collected between March and May 2024. The majority of respondents were general ophthalmologists (51%) and pediatric ophthalmologists (43%). They came from all regions of Brazil, but more than half (52%) were from the Southeast region. Most participants (30%) had over 20 years of clinical practice experience. A significant proportion (89.2%) treated progressive myopia. The most requested complementary exams were optical biometry (83.78%) and corneal topography or tomography (69.59%). Behavioral measures were considered the most effective myopia treatment strategies by 41.2% of the respondents, followed by optical (33.8%) and pharmacological interventions (25%). Most recommended spending more time outdoors (94.59%) and reducing screen time (93.92%). Spectacle lenses for myopia (83.11%) and 0.025% atropine eye drops (54.73%) were the most prescribed treatments after the recommendation of environmental and behavioral changes.

CONCLUSION: This study presents a novel analysis of the clinical strategies for myopia control among Brazilian ophthalmologists. Understanding current clinical practices and identifying possible improvements are essential steps toward developing evidence-based guidelines and professional education aimed at improving patient care.

Keywords: Myopia/epidemiology; Refractive errors; Contact lenses; Myopia/drug therapy; Atropine/therapeutic use; Ophthalmologists; Practice patterns, physicians’; Surveys and questionnaires; Brazil/epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

In the past decade, numerous studies have identified a significant increase in the global prevalence of myopia and high myopia (refractive error ≥ −6.00 diopters)(1,2). The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified myopia as the refractive error with the highest risk of triggering severe ocular pathologies, including legal blindness(3). Estimates suggest that the number of people with high myopia could increase sevenfold between 2000 and 2050, making it one of the leading causes of permanent blindness(1). Thus, understanding the risk factors for myopia and developing effective strategies to manage it and prevent its progression is a global medical priority(4,5).

The growing prevalence of myopia has been documented in various parts of the world. In China, an analysis of individuals aged ≤20 years reported an overall myopia prevalence of 36.6%. Projections indicated a substantial increase in both myopia and high myopia, with estimates suggesting that, by 2050, approximately 61.3% of Chinese children would be myopic and 17.6% would have high myopia(2). However, the prevalence of myopia varies between regions and ethnicities. In Latin America, a meta-analysis reported an overall prevalence of 8.61% among children and adolescents aged 3-20 years(6). Epidemiological studies in Brazil have found rates similar to those in neighboring countries. The largest Brazilian population-based study to date included 17,973 children (mean age 8.24 ± 3.54 years) and reported a prevalence of 7.7%(7,8). South American studies have predominantly focused on school-aged children and have used smaller, less heterogeneous samples than the large cohorts seen in research from East Asia(2).

Ongoing research is evaluating various strategies for myopia control, but existing treatment options are primarily aimed at slowing its progression(4,9). These measures include behavioral recommendations, such as spending more time outdoors and reducing screen time(10-12), as well as pharmacological interventions such as low-dose atropine eye drops (0.01%-0.05%)(13-16). Optical modalities include special lens designs for glasses(16), multifocal contact lenses that incorporate areas of peripheral defocus, and orthokeratology(17,18).

In Brazil, ophthalmologists are responsible for managing, treating, and monitoring patients with myopia. Since myopia typically emerges during the early school years and progresses relatively rapidly in the pediatric population(4,9), follow-ups are often conducted by pediatric ophthalmologists. While there is extensive literature on myopia control, there is a lack of national data on clinical practice patterns among ophthalmologists in Brazil. The need to document these practices is particularly important given the absence of standardized protocols supported by evidence from Brazilian patients.

The present study aims to better understand the strategies commonly employed in clinical practice by both general Brazilian ophthalmologists and pediatric specialists, and the professional knowledge upon which these choices are based. Understanding the practices of these professionals will help guide interventions and identify gaps in their knowledge, leading to enhanced patient care.

METHODS

The data for this prospective cross-sectional study were collected using a structured, self-administered questionnaire. The content of the questionnaire was based on a review of the scientific literature. This included previous international studies on the opinions and practices of ophthalmologists in the management of myopia(19-24). designed to evaluate healthcare professionals’ strategies for managing myopia. Relevant questions were extracted from these and then adapted and reformulated to reflect the Brazilian context. Considerations used in this contextualization included between-country differences in the treatments available and in the guidelines for preventing and slowing myopia progression to which the different countries adhere. In Brazil, the relevant guidelines are those established by the Brazilian Society of Pediatric Ophthalmology (SBOP) and the Brazilian Society of Contact Lenses, Cornea, and Refractometry (SOBLEC)(25).

Once the questions were formulated, the questionnaire was subjected to internal validation by a medical team, including pediatric ophthalmologists, general ophthalmologists, pediatric ophthalmology fellows, and ophthalmology residents. This assessment aimed to determine the clarity and relevance of the questions and to identify any potential gaps or ambiguities that needed to be addressed or corrected. The final questionnaire, after the necessary modifications, is shown in Appendix 1.

The questionnaire was then formatted for online administration using Google Forms (Google Corp., Mountain View, CA, USA). An invitation to participate was posted via the social media platform, WhatsApp (Facebook, Inc., USA). This was sent to SBOP members and other relevant online groups of pediatric ophthalmologists and of general ophthalmologists who treat both children and adults in Brazil. Data were collected online between March and May 2024. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and was preceded by a brief explanation of the study.

The questionnaire consisted of 10 questions, of which nine were multiple-choice. The questions gathered the following information from each respondent:

Their level of medical specialization (multiple choice: pediatric ophthalmologist, general ophthalmologist, pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus fellow, or ophthalmology resident).

The Brazilian state in which they practice (multiple choice from a list of Brazilian states).

Their years of experience in pediatric ophthalmology (multiple choice: 0-5, 5-10, 10-15, 15-20, or >20 years).

Whether they provide treatment for myopic patients with progressive refractive error increase (multiple choice: yes or no).

If they answered “no” to the previous question, the main reason they do not provide this treatment (multiple choice: insufficient demand, lack of technical knowledge, parents are not interested in pursuing these treatments for their children, a lack of consistent scientific evidence for the optimum treatment choices in the literature).

Whether they request complementary ophthalmic exams for the follow-up of myopic patients (multiple choice: yes or no).

If “yes”, which complementary ophthalmic exam do they request (multiple choice: optical biometry, ocular ultrasound, corneal topography/tomography, fundus photography, or other/unspecified). Multiple responses to this question were allowed when applicable.

The treatment modality they consider most effective for controlling the progression of myopia (multiple choice: behavioral, e.g., ultraviolet light exposure, reduced screen time, etc.; optical, i.e., glasses with peripheral defocus lenses, specialized contact lenses with peripheral defocus, or orthokeratology; or pharmacological, i.e., atropine eye drops).

The treatment(s) they prescribe to patients to reduce myopia progression: (multiple choice: increased outdoor time; reduced screen time; 0.01%, 0.025%, or 0.05% atropine eye drops; glasses with special lenses for myopia [peripheral defocus]; specialized contact lenses for myopia [peripheral defocus]; orthokeratology; none of the above). Multiple responses were allowed when applicable.

Any additional treatment modalities beyond the listed options they prescribe to slow or reduce myopia progression (open-ended responses requested).

The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. As no information about specific patients was requested in the questionnaire and the data provided was anonymous and could not be used to identify any of the participants, approval from our institution’s ethics committee was not required, per the resolution no. 510 of the Brazilian National Health Council, 2016(26).

Statistical analysis

The descriptive measures used to describe the data in this study were mean ± standard deviation, median and interquartile range, and frequency and percentage. Chi-square tests of independence were employed to investigate associations between categorical variables(27). Fisher’s exact test for small sample sizes was used to assess associations between categorical variables when the chi-square test assumptions were not met(28). All statistical analyses were performed using R, v. 4.3.2 open-source statistical software(29). The significance level was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

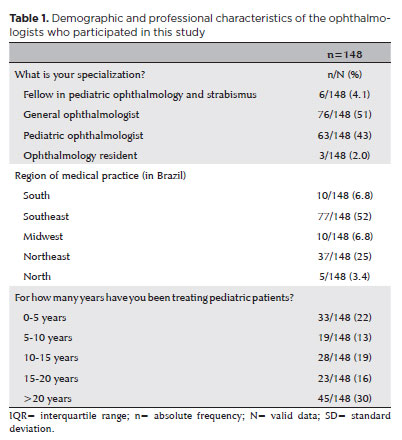

This study included 148 participants, the majority of whom were general ophthalmologists (51%) and pediatric ophthalmologists (43%). Our demographic analysis of the sample revealed that there were respondents from all regions of the country. While 24 Brazilian states were represented, with 52% practicing in the Southeast region. The largest proportion of participants reported having >20 years of clinical experience in pediatric ophthalmology (30%), followed by 22% with <5 years (Table 1).

In our sample, 89.2% of participants reported that they treated patients with progressive refractive error increase, while the remainder did not provide treatment for these patients. The predominant reason for not providing this service was insufficient demand (76.5%).

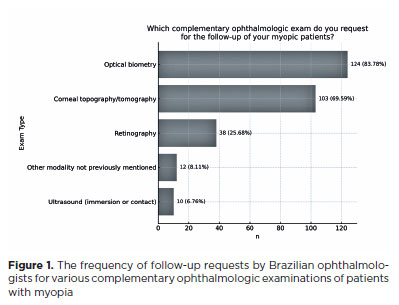

Figure 1 displays the ophthalmologic exams that our respondents recommended in the follow-up of patients with myopia. Participants had the option to select multiple exams, as applicable. Among the choices of exams presented in the question, optical biometry was the most frequently selected. This is likely because of its utility in the monitoring of axial length, which is a key marker of myopia progression.

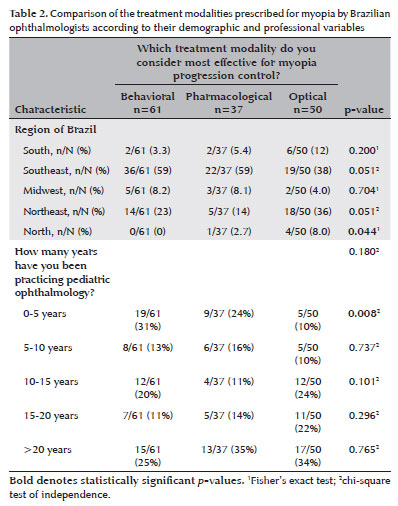

When asked about the most effective treatment modality, 41.2% of participants felt that behavioral measures are the most effective. A further 33.8% chose optical measures, and 25% pharmacological measures. Comparing these responses between participants from different regions of Brazil, we found only one significant difference. This was between the respondents from the Northern region, who favored optical modalities, and the rest of the sample. We next compared the treatment modality believed to be most effective between respondents with differing amounts of professional experience. We found significantly more of the respondents with <5 years of experience (31%) to consider behavioral measures the most effective compared to the rest of the sample (Table 2).

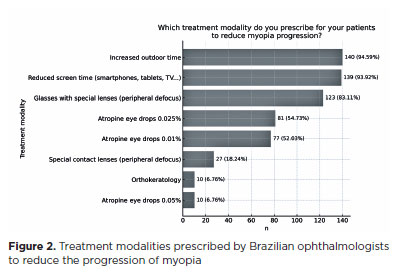

We next assessed which myopia treatments our participants reported prescribing most frequently in clinical practice. Figure 2 displays the distribution of prescribed treatment modalities. Participants had the option to select multiple treatment modalities in response to this question to allow a broader, more accurate representation of their practices.

As myopia usually begins in childhood and often stabilizes in adulthood, pediatric patients are the demographic most commonly treated for this condition. We compared the questionnaire responses of pediatric ophthalmologists and nonpediatric ophthalmologists. The nonpediatric group included general ophthalmologists, pediatric ophthalmology fellows, and residents. We observed a statistically significant difference between the two groups in the prescription of atropine 0.025% and 0.05%, and of special eyeglasses lenses (peripheral defocus), with pediatric ophthalmologists prescribing these treatments significantly more often (Table 3).

In their responses to our open-ended question about other treatments prescribed for myopia, some participants mentioned the “20-20-20 rule”. The rule recommends taking a visual break from visual tasks viewed at short range every 20 minutes by looking at an object at least 20 feet (6 meters) away for 20 seconds. This practical strategy exemplifies the behavioral guidance commonly recommended to patients with myopia in clinical settings.

DISCUSSION

In recent decades, there has been a global rise in myopia. This has led to significant research advances and the development of new therapeutic options for myopia control(1-4). Consequently, we need to understand how these strategies are being implemented by ophthalmologists in clinical practice to inform future evidence-based guidelines.

Our study included 148 Brazilian ophthalmologists, of whom 89.2% reported offering some form of treatment for patients with progressive myopia. This finding is consistent with previous international surveys of eye care professionals, which have also found high levels of engagement in myopia management(19-24).

In the Brazilian context, Cross-sectional studies of school-aged children in Brazil have shown uncorrected refractive errors to be the leading cause of visual impairment in this demographic, followed by amblyopia and retinal disorders(7,30). Among the conditions that result from refractive errors, myopia is the primary cause of treatable visual impairment(7). Although the myopia rates reported in Brazil are lower than those in other regions, such as East Asia(2,3), Brazilian ophthalmologists have expressed concern about the rapidly growing prevalence(25). When myopia first presents, early intervention is crucial, as the condition progresses most rapidly in young children and tends to slow over time(4).

Brazil is a large country with diverse geographical, cultural, and socioeconomic conditions across its territory. This is likely to affect the distribution of risk factors associated with myopia, which include particular ethnicities, the educational demands on children, and the amount of time spent outdoors(4,31). While all regions of Brazil were represented by the respondents to our survey, 52% of the participating professionals were practitioners from the Southeast region. This distribution is concordant with national data on the distribution of ophthalmologists in Brazil. The Southeast also concentrates the highest income levels and the most universities and research centers. This likely facilitates access to continuing education and advanced medical treatments. However, our comparison of participants from different regions showed no statistically significant differences, other than between the Northern region, which represented only 3.4% of our respondents, and the rest of the sample.

Most of the existing data on myopia control practices are from Asia, Europe, North America(19-24), and surveys by the International Myopia Institute (IMI)(19,20). Thus, the insights provided by our study offer valuable additional data specific to Brazil, with relevance to countries with similar healthcare systems. It is hoped that our findings will help to inform the strategies of individual practitioners and the standardized guidelines for myopia management in low- and middle-income settings.

When asked about the most effective therapeutic modality for controlling myopia progression, most participants (41.2%) favored behavioral measures, such as increased exposure to ultraviolet light, reduced use of electronic devices, and limiting near-work activities (<25 cm). This aligns with the findings of a global survey by the IMI in 2022, in which practitioners worldwide ranked behavioral interventions highly due to their noninvasive nature and low cost(20). Optical (33.8%) and pharmacological treatments (usually low-dose atropine eye drops) (25.0%) were also considered effective by a significant portion of our respondents. It is important to note the barriers to more widespread adoption of optical and pharmacological therapies in some parts of the world relating to professional training, patient access, and high treatment costs(25). The need to overcome these obstacles is more pressing than ever, given the rapid escalation in myopia rates.

Our comparison of respondents with different medical specializations showed that pediatric ophthalmologists (42.6%) prescribe significantly more atropine at doses of 0.025% (p<0.001), and 0.05% (p=0.002), and peripheral defocus lenses (p=0.003) compared to nonpediatric ophthalmologists (57.4%). The specialization and greater experience with pediatric patients may contribute to the greater confidence of pediatric clinicians in prescribing myopia progression control treatments.

Our respondents reported the utilization of a notable number of complementary exams for their myopic patients. This indicates their adherence to current national guidelines, which recommend the regular monitoring of patients with myopia at risk of progression with refraction under cycloplegia, optical biometry, and corneal topography(25). It also complies with international protocols encouraging the use of axial length measurement as a key progression marker in myopia(25,31). However, our respondents’ occasional use of tests such as fundus photography and ocular ultrasound, which are not routinely recommended, may indicate either a cautious clinical approach or variability in access to diagnostic resources. These findings underscore the need for continuing education of practitioners, standardized follow-up protocols, and the optimization of resources in diverse clinical settings.

In our evaluation of the myopia treatments most prescribed by Brazilian professionals in their clinical practice, environmental control recommendations stood out, with 94.6% of participants recommending increased outdoor time and 93.9% suggesting reduced screen time. This strong emphasis on behavioral measures reflects the well-established role of environmental factors in myopia progression, which is well-supported by randomized controlled trials(2,11,12). Reduced exposure to ultraviolet light; the increasing demands of modern educational systems, especially on younger children in East Asian countries; excessive exposure to screens on devices such as tablets and smartphones; as well as other near-work activities, are considered important risk factors for more severe myopia and faster progression rates(4,31). When we compared respondents based on their years of medical practice, we observed that a significantly higher proportion of those with <5 years of practice favored these behavioral measures than the rest of the sample. This may be because they are cost-free and require less specialized expertise.

Eyeglasses designed for myopia control were prescribed by 83.1% of participants, making it the most prescribed treatment after environmental control. This finding is consistent with the latest global data from the IMI, which reports a high frequency of eyeglass prescriptions for myopia control(20). The preference for this approach may be partially attributable to the growing number of studies supporting the efficacy of this intervention(17). Other contributing factors may include the fact that no additional equipment is required for its prescription, the lack of infection risk compared to contact lenses, and its acceptance by children(25).

We found that a significantly higher proportion of pediatric ophthalmologists (25%) reported prescribing special contact lenses for myopia control compared to nonpediatric ophthalmologists (13%). This trend may reflect greater familiarity with this intervention among those who routinely manage younger patients and their greater exposure to the most current myopia management strategies. Overall, these lenses were prescribed by 18.2% of participants. According to Wolffsohn et al. suggest that there is greater concern among professionals when prescribing soft contact lenses for young patients with myopia due to issues with their cost, their safety, the preferences of patients and their parents, and the minimum age requirements for contact lens prescription(20). The Brazilian guidelines emphasize that, in a country with limited resources, access to contact lenses is not feasible for most of the population, making cost a critical factor. The MiSight lens (CooperVision, Pleasanton, CA, USA) is the only disposable variety approved for myopia control in Brazil(25).

Orthokeratology was prescribed by 6.8% of our respondents. This approach requires special professional training and is less widely available than the other options. Nevertheless, both myopia contact lenses and orthokeratology are considered safe and effective methods of controlling myopia progression(25,31).

To evaluate the rates of pharmacological prescriptions for myopia, we presented our participants with the pharmacological options of prescribing atropine eye drops at concentrations of 0.01%, 0.025%, and 0.05%. These are considered low doses(14,15). Recent studies have estimated rates of myopia progression control at these concentrations of 40%-70% in the Chinese population(13-15). A total of 54.73% of participants reported prescribing 0.025% atropine. This rate was higher among pediatric (71%) than nonpediatric ophthalmologists (42%). The lack of consensus on the ideal atropine dosage for myopia control may discourage some professionals from using it. There is currently no agreed-upon initial dosage, and the appropriate method for discontinuing treatment to avoid potential rebound effects is uncertain(21,31). Furthermore, access to low-dose atropine is limited. In Brazil, it is only available through specialized compounding pharmacies, as there is no standardized formulation. Consequently, there is considerable variation in labeling practices, concentrations, pH, osmolarity, and excipients, posing considerable challenges in terms of safety, efficacy, and cost consistency(31).

Despite these uncertainties, a global survey of members of the International Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Council and the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus revealed that the most prescribed myopia treatment is the topical application of 0.01% atropine eye drops(21). However, this may change, as the results of more recent research on the use of 0.01% atropine in school-aged children, including randomized controlled clinical trials such as the LAMP study, and a study by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, have not supported the use of this dosage to slow myopia progression or axial elongation(16).

The limitations of this study include possible false or duplicate responses from participants due to the lack of identity verification. However, this strategy was adopted by the authors to maintain response anonymity, and it is hoped that this anonymity encouraged more honest responses, balancing the potential for false responses resulting from the lack of accountability. The greater dissemination of participation requests among professional groups from the Southeast region may have led to a geographical bias in the sample, limiting the national representativeness of our data. In light of these constraints, we recommend cautious interpretation of our results. Further studies are needed to validate our findings across other Brazilian states with more representative samples.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive and novel overview of the strategies used by Brazilian ophthalmologists to manage myopia in clinical practice. In the context of rapid global scientific advances and newly emerging therapeutic options, our findings demonstrate the importance of understanding how research evidence is integrated into routine clinical practice. These insights may be utilized to inform national strategies, guide the implementation and regulation of effective and accessible myopia control measures in developing countries, and help identify less effective approaches, ultimately enhancing patient care.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Significant contribution to conception and design: Raíra Fortuna Cavaliere Mendes Moraes, Carolina P. B. Gracitelli, Célia Regina Nakanami, Julia Dutra Rossetto. Data Acquisition: Raíra Fortuna Cavaliere Mendes Moraes, Célia Regina Nakanami. Data Analysis and Interpretation: Raíra Fortuna Cavaliere Mendes Moraes, Carolina P. B. Gracitelli, Célia Regina Nakanami, Julia Dutra Rossetto. Manuscript Drafting: Raíra Fortuna Cavaliere Mendes Moraes, Carolina P. B. Gracitelli, Célia Regina Nakanami, Julia Dutra Rossetto. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Raíra Fortuna Cavaliere Mendes Moraes, Carolina P. B. Gracitelli, Célia Regina Nakanami, Julia Dutra Rossetto. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Raíra Fortuna Cavaliere Mendes Moraes, Carolina P. B. Gracitelli, Célia Regina Nakanami, Julia Dutra Rossetto. Statistical analysis: Raíra Fortuna Cavaliere Mendes Moraes, Carolina P. B. Gracitelli. Obtaining funding: not applicable. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Raíra Fortuna Cavaliere Moraes, Carolina P. B. Gracitelli, Célia Regina Nakanami, Julia Dutra Rossetto. Research group leadership: Julia Dutra Rossetto.

REFERENCES

1. Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, Jong M, Naidoo KS, Sankaridurg P, et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(5):1036-42. Comment in: Ophthalmology. 2017;124(3): e24-e25.

2. Pan W, Saw SM, Wong TY, Morgan I, Yang Z, Lan W. Prevalence and temporal trends in myopia and high myopia children in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis with projections from 2020 to 2050. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2025;55:101484.

3. World Health Organization. Myopia and high myopia [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2024 [cited 2024 May 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/blindness/causes/MyopiaReportfor-Web.pdf

4. Jonas JB, Ang M, Cho P, Guggenheim JA, He MG, Jong M, et al. IMI-prevention of myopia and its progression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62(5):6.

5. Leshno A, Farzavandi SK, Gomez-de-Liaño R, Sprunger DT, Wygnanski-Jaffe T, Mezer E. Practice patterns to decrease myopia progression differ among pediatric ophthalmologists around the world. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(4):535-40.

6. Guedes J, da Costa Neto AB, Fernandes BF, Faneli AC, Ferreira MA, Amaral DC, et al. Myopia prevalence in Latin American children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e63482.

7. Salomão SR, Cinoto RW, Berezovsky A, Mendieta L, Nakanami CR, Lipener C, et al. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in low-middle income school children in São Paulo, Brazil. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(10):4308-13.

8. Fernandes AG, Vianna RG, Gabriel DC, Ferreira BG, Barbosa EP, Salomão SR, et al. Refractive error and ocular alignment in school-aged children from low-income areas of São Paulo, Brazil. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024;24(1):452.

9. Flitcroft DI, He M, Jonas JB, Jong M, Naidoo K, Ohno-Matsui K, et al. IMI-defining and classifying myopia: a proposed set of standards for clinical and epidemiologic studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(3):M20-M30.

10. Rose KA, Morgan IG, Smith W, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P, Saw SM, et al. Myopia, lifestyle, and schooling in students of Chinese ethnicity in Singapore and Sydney. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(4):527-30.

11. He X, Sankaridurg P, Wang J, Chen J, Naduvilath T, He M, et al. Time outdoors in reducing myopia: a school-based cluster randomized trial with objective monitoring of outdoor time and light intensity. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(11):1245-54.

12. Wu PC, Chen CT, Lin KK, Sun CC, Kuo CN, Huang HM, et al. Myopia prevention and outdoor light intensity in a school-based cluster randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(8):1239-50. Comment in: Ophthalmology. 2018;125(8):1251-2.

13. Yam JC, Jiang Y, Tang SM, e Law AKP, Chan JJ, Wong E, et al. Low-concentration atropine for myopia progression (LAMP) study: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of 0.05%, 0.025%, and 0.01% atropine eye drops in myopia control. Ophthalmology. 2019;12691):113-24. Comment in: Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):125-6.

14. Chia A, Chua WH, Cheung YB, Wong WL, Lingham A, Fong A, et al. Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia: safety and efficacy of 0.5%, 0.1%, and 0.01% doses (Atropine for the Treatment of Myopia 2). Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):347-54. Comment in: Ophthalmology. 2012;119(8):1718; author reply 1718-9. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(12):2653; author reply 2653-4.

15. Repka MX, Weise KK, Chandler DL, Wu R, Melia BM, Manny RE, et al; Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Low-dose 0.01% atropine eye drops vs. placebo for myopia control: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141(8):756-65. Comment on: JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141(8):766-7.

16. Lam CS, Tang WC, Zhang HY, Lee PH, Tse DYY, Qi H, et al. Long-term myopia control effect and safety in children wearing DIMS spectacle lenses for 6 years. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):5475.

17. Walline JJ, Walker MK, Mutti DO, Jones-Jordan LA, Sinnott LT, Giannoni AG, et al; BLINK Study Group. Effect of high add power, medium add power, or single-vision contact lenses on myopia progression in children: the BLINK randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(6):571-80. Comment in: JAMA. 2020;324(6):558-9.

18. Cho P, Cheung SW. Retardation of myopia in orthokeratology (ROMIO) study: a 2-year randomized clinical trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(11):7077-85.

19. Wolffsohn JS, Calossi A, Cho P, Gifford K, Jones L, Jones D, et al. Global trends in myopia management attitudes and strategies in clinical practice-2019 update. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020;43(1):9-17.

20. Wolffsohn JS, Whayeb Y, Logan NS, Weng R; International Myopia Institute Ambassador Group. IMI-global trends in myopia management attitudes and strategies in clinical practice: 2022 update. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64(6):6.

21. Zloto O, Wygnanski-Jaffe T, Farzavandi SK, Gomez-de-Liaño R, Sprunger DT, Mezer E. Current trends among pediatric ophthalmologists to decrease myopia progression: an international perspective. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(12):2457-66. Erratum in: Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(10):2015-7.

22. Eppenberger LS, Sturm V. Myopia management in daily routine: a survey of European pediatric ophthalmologists. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2023;240(4):581-6.

23. Martínez-Pérez C, Villa-Collar C, Santodomingo-Rubido J, Wolffsohn JS. Strategies and attitudes on the management of myopia in clinical practice in Spain: 2022 update. J Optom. 2024;17(1):100496.

24. Douglass A, Keller PR, He M, Downie LE. Knowledge, perspectives and clinical practices of Australian optometrists in relation to childhood myopia. Clin Exp Optom. 2020;103(2):155-66.

25. Ejzenbaum F, Schaefer TM, Cunha C, Rossetto JD, Godinho IF, Nakanami CR, et al. Guidelines for preventing and slowing myopia progression in Brazilian children. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2024; 87(5):e2023-0009.

26. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Resolução n. 510, de 7 de abril de 2016. Esta Resolução dispõe sobre as normas aplicáveis a pesquisas em Ciências Humanas e Sociais cujos procedimentos metodológicos envolvam a utilização de dados diretamente obtidos com os participantes ou de informações identificáveis ou que possam acarretar riscos maiores do que os existentes na vida cotidiana, na forma definida nesta Resolução [Internet]. Brasilia: MS; 2016. [citado em 2025 Jan 21]. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/conselho-nacional-de-saude/pt-br/atos-normativos/resolucoes/2016/resolucao-no-510.pdf/view

27. Turhan NS. Karl Pearson’s chi-square tests. Educ Res Rev. 2020; 16(9):575-80.

28. Lee SW. Methods for testing statistical differences between groups in medical research: statistical standard and guideline of life cycle committee. Life Cycle. 2022;2(1):e1.

29. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023. [cited 2024 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/

30. Barbosa EP, Fernandes AG, Vianna RG, Salomão SR, Campos M. Vision screening in school children from low-income areas of São Paulo city: frequency and causes of visual impairment and blindness. Med Res Arch [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Dec 19];9(4):2376. Available from: https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/2376

31. World Society of Paediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (WSPOS). Myopia Consensus Statement 2025 [Internet]. London: WSPOS; 2025. [cited 2025 Jul 27] Available from: https://wspos.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Myopia-Consensus-Statement2025.pdf

Submitted for publication:

June 25, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

October 8, 2025.

Data Availability Statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included in the manuscript.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior

Associate Editor: Dácio C. Costa

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.