Camila F. Netto1; Carolina P. B. Gracitelli1; Heloisa Russ2; Denise F. Barroso de Melo Cruz3; Nubia Vanessa dos Anjos Lima4; Heloisa Andrade Maestrini5

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2025-0051

ABSTRACT

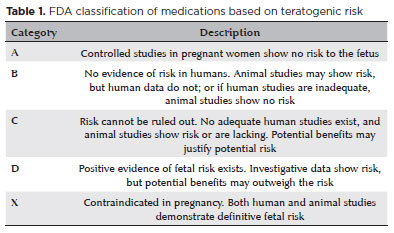

Glaucoma is a progressive optic neuropathy that can cause irreversible blindness, though it rarely affects women of reproductive age. Its management during pregnancy and lactation is particularly challenging because of the potential impact of intraocular pressure fluctuations on disease progression and the risks of treatment to both the mother and fetus. Physiological changes in pregnancy, such as decreased intraocular pressure and hormonal alterations, may influence disease activity but do not guarantee disease stability. Preconception counseling plays a key role in mitigating risks and tailoring treatment strategies. Many glaucoma medications carry teratogenic risks, with brimonidine being the only US Food and Drug Administration Category B drug. Surgical interventions – including laser trabeculoplasty and minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries – offer alternative options but require careful timing and consideration of fetal safety. Multidisciplinary collaboration is essential to optimize maternal and neonatal outcomes. This review summarizes evidence-based approaches for glaucoma management during pregnancy and lactation, highlighting clinical considerations, therapeutic strategies, and patient-centered care.

Keywords: Pregnancy complications; Glaucoma; Lactation; Parturition; Intraocular pressure

INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Glaucoma is a slowly progressive optic neuropathy that can lead to irreversible blindness. Although its incidence is highest among older adults, it may also affect women of reproductive age in rare cases(1). The coexistence of glaucoma and pregnancy is uncommon, with the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma estimated at 0.48%, 0.42%, and 0.73% among women aged 15–24, 25–34, and 35–44 years, respectively(2). This frequency is expected to rise as more women delay childbearing and as advances in reproductive medicine enable conception at older ages(3). In addition, women with congenital, juvenile, or secondary forms of glaucoma may also become pregnant.

A study conducted in the United Kingdom reported that more than one-quarter of ophthalmologists had managed pregnant patients with glaucoma(4). Among these, most continued preexisting treatment regimens, while 34% opted for observation alone. Notably, 31% expressed uncertainty regarding how to proceed if active treatment became necessary.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) typically decreases during pregnancy, particularly in the second and third trimesters. This reduction is accompanied by decreased diurnal IOP fluctuations and increased retrobulbar blood flow(5). However, despite these physiological changes, some patients experience disease progression and still require medical or surgical intervention(6).

Managing glaucoma in pregnant women remains challenging because ocular hypotensive agents may pose potential risks to both the mother and the fetus(7-9). Clinicians must carefully balance maternal disease control against fetal safety. Ethical and legal restrictions on clinical research in pregnant populations further limit safety data, meaning that much of the current understanding of drug risk is based on theoretical considerations and animal studies rather than robust human trials(10,11).

After childbirth, the excretion of ocular hypotensive medications into breast milk and their potential effects on the infant must also be considered.

The absence of clear, evidence-based guidelines for managing glaucoma during pregnancy and lactation further complicates clinical decision-making. Because this condition is rare in reproductive-age women, large randomized clinical trials and systematic studies are scarce. Consequently, management relies heavily on individualized risk–benefit assessments that take into account disease stage, gestational age, and the safety profile of available treatment options(12).

Preconception counseling

Preconception ophthalmic counseling for women with glaucoma is essential to safeguard maternal health and minimize fetal risk during pregnancy. Although glaucoma is less common among women of reproductive age, advances in reproductive technology and the trend toward later childbearing have increased the likelihood of its coexistence with pregnancy(1,10,13).

Such counseling allows clinicians to explore alternative treatment strategies and optimize therapy before conception, thereby reducing potential risks to the fetus. Most antiglaucoma medications are classified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as Category C, indicating uncertain safety in humans and evidence of adverse effects in animal studies. Brimonidine and dipivefrine are exceptions, categorized as Category B, suggesting a more favorable safety profile based on animal data(14). However, dipivefrine is no longer available in Brazil. Even when administered topically, these drugs undergo systemic absorption through the nasolacrimal duct(15), which may lead to placental transfer and fetal exposure. Postpartum, exposure may continue through breastfeeding, as animal studies have demonstrated the presence of antiglaucoma drugs in the milk of lactating women(16,17).

Given the risks and unique challenges of managing glaucoma during pregnancy, regular monitoring is essential. Although IOP generally decreases during pregnancy, some patients continue to require therapy, and those with previously stable disease may experience IOP elevation(18). In a retrospective study by Brauner et al. involving 28 eyes from 15 pregnant glaucoma patients, 36% of eyes showed increased IOP and/or progression of visual field loss, underscoring the need for close follow-up during pregnancy(6).

When pharmacologic treatment is required, pressure control strategies should aim to minimize systemic drug absorption. Techniques such as nasolacrimal occlusion, lacrimal plugs, or eyelid closure can be employed. Zimmerman et al. demonstrated that nasolacrimal occlusion or eyelid closure for 5 seconds reduced systemic absorption by up to 60%(19).

In planned pregnancies, the optimal strategy to control maternal IOP while minimizing fetal risk should be carefully determined in advance through a multidisciplinary approach involving the patient's healthcare team(20). The intensity of therapy should be guided by disease severity: low-risk glaucoma can often be managed conservatively without active treatment during pregnancy, whereas high-risk cases may require medical or even surgical intervention(21).

Accordingly, preconception counseling remains the most effective and recommended strategy for women of childbearing age with glaucoma who are planning to conceive.

OCULAR CHANGES DURING PREGNANCY

Intraocular pressure

IOP decreases by approximately 10% during pregnancy(22-24). A statistically significant decline is typically observed from the first to the third trimester and may persist for up to 1 month postpartum(25-29). Diurnal IOP fluctuations are also reduced during pregnancy(30). This decrease is primarily attributed to enhanced aqueous humor outflow through increased uveoscleral flow and reduced episcleral venous pressure(25,26,28,29,31). Hormonal changes, particularly elevated progesterone and relaxin levels, further promote aqueous drainage(12,20).

This IOP reduction also occurs in patients with preexisting ocular hypertension, although the onset may vary. Normotensive women usually exhibit a significant decrease around the 18th week of gestation, whereas hypertensive patients may experience it later(32). Despite these hormonal effects, approximately 10% of pregnant glaucoma patients may show increased IOP or disease progression during pregnancy(8).

Corneal changes

Pregnancy can cause decreased corneal sensitivity, increased thickness, and alterations in curvature. Corneal sensitivity declines progressively throughout pregnancy and returns to baseline within weeks after delivery(22,33,34). Corneal thickness typically increases by about 3%, likely due to hormonally mediated fluid retention(35,36). These changes are generally transient and resolve after childbirth(37).

Retrobulbar blood flow

Pregnancy is associated with increased retrobulbar blood flow, which may offer some protection against glaucoma progression(3,38-40). Elevated estrogen levels during gestation promote endothelial-dependent vasodilation, contributing to this hemodynamic effect(39,40).

Visual field during pregnancy

Several transient visual field changes have been documented during pregnancy, including bitemporal contraction, concentric contraction, and enlargement of the blind spot. The underlying mechanisms are not fully understood, but multiple theories have been proposed. In a study by Akar et al.(41), the mean sensitivity threshold in pregnant women increased significantly during the third trimester, and all observed visual field alterations resolved completely within 10 days postpartum. One potential explanation for these changes is the physiological enlargement of the pituitary gland during pregnancy, which may exert pressure on the optic chiasm and result in transient visual field defects(3,5,42).

LABOR, CESAREAN SECTION, AND GLAUCOMA

Currently, approximately one in three births occurs via cesarean section. A retrospective study reported that ophthalmologic indications accounted for 2.04% of cesarean deliveries, with myopia comprising 57% of cases and glaucoma 5%(43). The most relevant data to date come from studies by Avasthi(44) and Meshi(45), which documented only slight fluctuations in IOP during vaginal delivery, with values returning to baseline within 72 hours postpartum.

Indications for cesarean and vaginal delivery

In patients with glaucoma, the choice between vaginal delivery and cesarean section remains controversial. This debate primarily centers on concerns about increased IOP and reduced ocular perfusion pressure associated with the Valsalva maneuver during vaginal delivery(46). Previous studies have shown that IOP can fluctuate depending on the stage of labor(44,45). It has also been hypothesized that eelevated oxytocin levels during labor may induce capillary constriction and decrease aqueous humor flow(44). Although no direct evidence links oxytocin to increased IOP, the potential implications of transient pressure elevations on glaucoma progression remain unclear due to the absence of dedicated studies(47). In addition, significant blood loss during labor may lead to transient hypotension and ischemia, which could theoretically increase the risk of optic nerve damage(48).

The Valsalva maneuvers associated with normal vaginal delivery raise particular concerns in patients with advanced glaucoma, where even small fluctuations in IOP could theoretically exacerbate disease progression. Similar concerns apply to patients who have undergone trabeculectomy with thin, fragile filtering blebs, which may be at risk of rupture. These risks are presumed to increase with prolonged labor. However, it is important to emphasize that no clinical evidence currently supports these theoretical concerns in the context of labor among glaucoma patients(12).

A recent survey in the United States found that 25% of obstetricians recommend cesarean delivery for women with glaucoma, and 3.6% of ophthalmologists have advised elective pregnancy termination in patients with advanced or uncontrolled disease(49). These recommendations are largely based on theoretical models associating Valsalva maneuvers with increased maternal IOP during labor(50). At present, there is no robust evidence to justify altering standard obstetric protocols – such as recommending cesarean delivery or pregnancy termination – solely on the basis of ocular comorbidities(8).

Indication of cesarean section in glaucoma-operated patients

In patients who have recently undergone glaucoma surgery – such as tube implantation or trabeculectomy – labor may pose significant risks because Valsalva maneuvers can affect vision, especially in the presence of complications like hypotony, choroidal effusion, or thin filtering blebs, which increase the risk of perforation or rupture. These procedures typically require several months of healing before delivery. Although no cases of vision loss related to labor have been reported in this context, cesarean section should be strongly considered for patients with recent incisional surgery(12). Whenever feasible, surgical intervention should be postponed until after pregnancy(10).

There is no clear consensus regarding cesarean delivery in patients with glaucoma-related visual defects. Ophthalmologists and obstetricians may differ in their opinions on whether vision-threatening changes justify pregnancy termination or cesarean section. A joint ophthalmologic–obstetric statement by the Polish Gynecology Society(51) recommends cesarean delivery for patients with advanced glaucoma and significant visual field loss but does not support cesarean section in patients with stable glaucoma or minimal visual field changes.

MEDICATION MANAGEMENT OF GLAUCOMA DURING PREGNANCY AND BREASTFEEDING

Medications

None of the currently available glaucoma medications have been proven to be completely safe during pregnancy. The US FDA classifies these drugs into categories based on animal studies, with the results extrapolated for clinical use in humans (Table 1)(52). Because randomized clinical trials in pregnant populations are lacking, no glaucoma medication has been assigned to Category A to date(52). Drugs in Categories B and C are generally considered to have a more favorable safety profile, whereas Category D medications should be avoided. Category X drugs are contraindicated because of their documented teratogenic effects. Among currently available agents, only brimonidine is classified as Category B for use during pregnancy.

The potential toxicity of antiglaucoma medications arises not only from the active compound but also from the added preservative, most commonly benzalkonium chloride (BAK). Depending on its concentration, BAK can disrupt the tear film and contribute to ocular surface disorders(53). In animal studies, BAK ha also demonstrated fetal toxicity; however, the concentrations used in these studies were substantially higher than those present in standard ophthalmic formulations. Whenever possible, preservative-free preparations are preferred for pregnant patients to minimize exposure. Table 2 summarizes the main fetal risks, adverse events, and clinical recommendations associated with the primary classes of antiglaucoma medications used during pregnancy, while table 3 outlines their safety profiles during lactation.

Topical anesthetics and fluorescein

Topical anesthetics such as proparacaine, oxybuprocaine, and tetracaine are not recommended for use during pregnancy or breastfeeding, according to their respective package inserts. Topical fluorescein; however, is classified as Category B. Although its use should be approached with caution, no teratogenic effects have been reported, and its intermittent application is generally considered acceptable for IOP measurements in pregnant or breastfeeding patients.

Prostaglandin analogs

Prostaglandin analogs are typically considered first-line agents for glaucoma management; however, they can cross the placental barrier and stimulate uterine contractions, potentially leading to preterm labor or spontaneous abortion. These agents act by binding to prostaglandin F2α receptors, stimulating luteolytic activity and oxytocin release(54). In animal studies, prostaglandins have been shown to induce abortion by degrading the corpus luteum, which supports early fetal development. Although this effect has been observed in rat models, no cases of preterm labor associated with ophthalmic prostaglandins have been reported in humans(55). Misoprostol, a prostaglandin widely used as an abortifacient in early pregnancy, has been linked to congenital anomalies such as Möbius syndrome when administered orally or intravaginally. However, it remains unclear whether the low concentrations in ophthalmic formulations pose a similar risk(56). This drug class is classified as Category C by the FDA because of the potential for preterm labor. Prostaglandin analogs are generally considered acceptable during lactation; while animal studies demonstrate excretion into breast milk, human data are inconclusive. Vyzulta (latanoprostene bunod 0.024%), a newer prostaglandin F2α analog(57), is metabolized into latanoprost and a nitric oxide donor fraction. Nitric oxide has been suggested to play a progestational role by enhancing uterine and fetal blood flow(58). However, the latanoprost concentration in Vyzulta is higher than in older formulations, making it a less suitable option during pregnancy. Therefore, it should still be considered a Category C medication, with no clear advantages over other prostaglandins for pregnant patients.

Beta-blockers

Beta-blockers are among the first-line treatments for glaucoma, acting by inhibiting cAMP in the ciliary epithelium to reduce aqueous humor production. Systemic beta-blockers are frequently used in obstetric practice to manage hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (DHEG); however, their use has been associated with maternal neurological complications – including lethargy, confusion, and depression – as well as intrauterine growth restriction in newborns(59). Due to these concerns, beta-blockers are classified as Category C by the FDA for use during pregnancy(60). Fetal cardiac effects have also been reported. Wagenvoort et al.(61) described a case of fetal bradycardia and arrhythmia related to maternal use of topical timolol, which improved after dose reduction. Topical timolol gel 0.1% administered once daily has been proposed as a safer alternative during pregnancy to minimize systemic exposure.

The safety profile of beta-blockers during lactation remains controversial, as these drugs are actively secreted into breast milk and may cause adverse effects in infants. Lustgarten and Podos(16) reported that timolol concentrations in breast milk were approximately six times higher than in plasma several hours after topical administration. In contrast, Madadi et al. did not observe this finding, highlighting variability in absorption and excretion patterns(16,62).

Sympathomimetics

Among topical antiglaucoma agents, brimonidine tartrate is the only drug classified as Category B for use during pregnancy. Other alpha-adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine and apraclonidine, are generally avoided because chronic use has been associated with adverse effects including nausea, vomiting, palpitations, and urinary difficulties(63). Animal studies indicate that brimonidine is relatively safer and better tolerated for long-term use. However, brimonidine readily crosses the blood–brain barrier and may cause central nervous system depression and apnea in newborns; therefore, it should be discontinued near delivery(20). Although considered relatively safe during pregnancy, it is believed to be excreted into breast milk, and current recommendations advise against its use in breastfeeding mothers.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are commonly used in both oral and topical formulations for glaucoma management. Systemic absorption of topically administered drugs is minimal and rarely causes systemic adverse effects, in contrast to the oral formulation. This distinction is particularly relevant for patients with chronic kidney disease, in whom impaired drug clearance may increase the risk of systemic toxicity(64). These agents are classified as Category C for use during pregnancy. Animal studies have reported congenital limb malformations following exposure to this drug class, while evidence from human studies remains inconclusive.

In the study by Falardeau et al.(65), no adverse effects were observed in pregnant participants treated with acetazolamide for intracranial hypertension; however, the sample size was insufficient to establish safety in pregnancy. Because of the potential risk of teratogenicity, particularly limb deformities, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors should be avoided during the first trimester. Low plasma levels of acetazolamide have been detected in infants exposed through breast milk, but no significant adverse effects have been reported. Consequently, the American Academy of Pediatrics considers the use of this drug class compatible with breastfeeding, provided that infants are closely monitored for potential adverse effects(66).

Parasympathomimetics

Parasympathomimetic agents, or cholinergics such as pilocarpine, are classified as Category C by the FDA(67). Although Kooner et al. reported no association between congenital anomalies and the use of topical cholinergic agents during the first 4 months of pregnancy, these medications are generally avoided because of their low tolerability and teratogenic effects observed in animal studies(68). In addition, there have been reports of hyperthermia, seizures, and restlessness in newborns exposed to these agents, making them unsuitable for use during the postpartum period and breastfeeding. As a result, parasympathomimetics are not considered first-line options during pregnancy or lactation.

Rho-kinase inhibitors

Rho-kinase inhibitors represent a relatively new class of antiglaucoma agents with a unique mechanism of action, primarily increasing aqueous humor outflow through the trabecular meshwork(51). Experimental studies in mice have suggested that these agents may influence uterine contraction and exert tocolytic effects(69). During the development of netarsudil (Rhopressa®, Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, CA, USA), no teratogenic effects were observed at physiological concentrations in animal models. However, given the drug's multiple molecular targets, the potential for malformations or fetal demise cannot be completely excluded(70). Because of insufficient human data and potential teratogenic risks, netarsudil should be avoided during pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester(10). Its safety profile during lactation remains unclear, and use is not currently recommended in breastfeeding women.

Osmotic agents

Osmotic agents such as mannitol and glycerol are classified as Category C by the FDA. One of the methods used for inducing abortion in the second trimester involves intra-amniotic administration of mannitol and urea, raising concerns about their fetal safety profile. To date, no animal or human studies have evaluated the use of osmotic agents for IOP control during pregnancy(71). Given the lack of safety data and their association with pregnancy termination methods, osmotic agents should be avoided in pregnant women unless absolutely necessary.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF GLAUCOMA DURING PREGNANCY AND BREASTFEEDING

Laser

Trabeculoplasty

Among the available treatment options, laser trabeculoplasty is considered the safest and least invasive intervention during pregnancy, posing minimal risk to the fetus(72). A case series on selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) demonstrated its effectiveness in reducing or eliminating the need for antiglaucoma medications during pregnancy(8,73).

Because trabeculoplasty has a latency period before its maximal hypotensive effect is achieved, the ideal timing for this procedure is before conception. However, as many pregnancies are unplanned and patients may present several weeks postconception, SLT remains a safe option throughout pregnancy. Nevertheless, because of its delayed onset of action, laser trabeculoplasty may not be the most appropriate choice when a rapid reduction in IOP is required.

Peripheral iridotomy and iridoplasty

For patients with primary angle-closure glaucoma, peripheral iridotomy and iridoplasty are considered safe and effective options for both prophylaxis and the management of acute angle closure during pregnancy. These laser procedures pose no known or theoretical risks to the fetus and can be performed when clinically indicated.

GLAUCOMA SURGERY

Certain glaucoma subtypes more commonly observed in young women – such as juvenile, congenital, traumatic, and inflammatory glaucomas – are often more severe and resistant to conservative treatment. In cases where medical or laser interventions fail to achieve adequate IOP control, surgical management should be considered.

Anesthetic risk

General anesthesia should be avoided during pregnancy because it can cause maternal hypotension, leading to reduced uterine blood flow and fetal hypoxemia(10,11). In addition, anesthetic agents can cross the placenta, potentially resulting in fetal cardiovascular and central nervous system depression, teratogenic effects, and preterm labor(11). Administration of general anesthesia during the first trimester has also been associated with an increased risk of low birth weight and neural tube defects(74).

Local anesthesia is considered safer. Lidocaine is classified as Category B, whereas bupivacaine is Category C(8). Bupivacaine should be avoided due to reports of fetal bradycardia when used in dental anesthesia, whereas lidocaine has not been associated with adverse fetal effects. Safer anesthetic techniques include retrobulbar block, sub-Tenon, or subconjunctival anesthesia with lidocaine, as well as topical lidocaine gel. It is important to note that retrobulbar anesthesia results in greater systemic absorption than subconjunctival or sub-Tenon anesthesia(75).

When is the best time for surgery?

Glaucoma surgery should ideally be performed before conception in women with advanced glaucoma requiring maximal medical therapy and at high risk of progression. If surgery is unavoidable during pregnancy, the first trimester should be avoided because organogenesis occurs during this period, increasing the risk of teratogenicity and miscarriage. The second trimester is considered the safest and most appropriate time for surgery, offering the best balance between maternal and fetal risks. In contrast, surgery in the third trimester carries additional challenges, including laryngeal edema, increased risk of gastric acid aspiration due to reduced gastroesophageal sphincter tone, and delayed gastric emptying, particularly in women with significant weight gain(11).

Which technique should be chosen?

The introduction of minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) has shifted surgical indications toward more conservative approaches. MIGS can be particularly advantageous for pregnant women, as these procedures are relatively quick, can be performed under topical or local anesthesia, and may reduce the need for chronic topical medications(10). Trabecular MIGS – including the iStent, goniotomy with Kahook Dual Blade, and gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy – offer the additional benefit of not requiring adjuvant antimetabolites.

For patients requiring greater IOP reduction, conventional incisional surgeries such as trabeculectomy or drainage tube implantation may be indicated. A case series reported favorable outcomes in pregnant women with juvenile glaucoma who underwent bilateral procedures during the second trimester, including trabeculectomy without antimetabolites and Ahmed or Baerveldt tube implantation, without adverse effects on the infants(76).

When selecting a surgical technique during pregnancy, priority should be given to achieving rapid and sustained IOP reduction while minimizing the need for postoperative hypotensive medications. Antimetabolites such as mitomycin-C and 5-fluorouracil are contraindicated at all stages of pregnancy due to documented teratogenicity in humans and their classification as Category X by the FDA. When trabeculectomy is indicated, surgeons should consider the higher risk of failure in pregnant patients, as younger patients often cannot use antimetabolites to enhance bleb survival.

Some authors advocate the use of tube shunts during pregnancy because they do not require antimetabolite support. However, potential limitations include transient IOP elevation during the hypertensive phase of the tube(77), delayed IOP reduction with nonvalved implants, and the frequent need for supplemental eye drops to achieve adequate pressure control.

As an alternative to filtering surgeries, cyclophotocoagulation represents a viable option during pregnancy. Both micropulse and continuous-wave laser (preferably using the "slow-coagulation" protocol) are minimally invasive, rapid procedures that can be performed under local anesthesia and do not require antimetabolite use, making them suitable for managing refractory glaucoma in pregnant patients.

Postoperative medication

Corticosteroids are classified as Category A by the FDA and are considered safe for use during pregnancy. Selection of antibiotic eye drops should be guided by their safety profile; cephalosporins, topical erythromycin, and polymyxin B are classified as Category B and are generally considered safe for pregnant women(78).

Surgery during lactation

During lactation, antimetabolites can be safely used in both trabeculectomy and needling procedures, as even systemic doses of 5-fluorouracil are not detected in breast milk(79). When possible, elective glaucoma surgery should be postponed until the postpartum period, when the likelihood of surgical success is higher and the risks to the infant are negligible.

In conclusion, although glaucoma during pregnancy is rare, it presents a significant clinical challenge requiring careful planning and individualized management. While IOP often decreases during pregnancy, some patients may still require medical or surgical intervention. Data on the safety of antiglaucoma medications in pregnancy remain limited. Laser trabeculoplasty represents a safe and effective method for controlling IOP during pregnancy. When surgery is necessary, procedures performed under local anesthesia without the use of antimetabolites can minimize fetal exposure and optimize maternal outcomes.

The management of glaucoma during pregnancy should be conducted by a multidisciplinary team, including an ophthalmologist, obstetrician, neonatologist, and other relevant healthcare professionals.

Whenever possible, pregnancy should be planned and coordinated to prevent disease progression in the mother and minimize potentially harmful interventions for the fetus or newborn. Ideally, treatment and counseling should begin prior to conception. Both clinical and surgical interventions should be decided collaboratively among healthcare professionals, the patient, and her family, taking into account her ophthalmological and overall clinical status. The overarching goal is to preserve maternal vision while minimizingrisks to the developing fetus, ensuring safe and effective management throughout pregnancy and postpartum.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS:

Significant contribution to conception and design: Camila Fonseca Netto, Carolina Pellegrini Barbosa Gracitelli, Heloisa Russ Giacometti, Nubia Vanessa dos Anjos Lima, Heloisa Andrade Maestrini. Data acquisition: Camila Fonseca Netto, Carolina Pellegrini Barbosa Gracitelli, Heloisa Russ Giacometti, Nubia Vanessa dos Anjos Lima, Heloisa Andrade Maestrini. Data analysis and interpretation: Camila Fonseca Netto, Carolina Pellegrini Barbosa Gracitelli, Heloisa Russ Giacometti, Nubia Vanessa dos Anjos Lima, Heloisa Andrade Maestrini. Manuscript drafting: Camila Fonseca Netto, Carolina Pellegrini Barbosa Gracitelli, Heloisa Russ Giacometti, Nubia Vanessa dos Anjos Lima, Heloisa Andrade Maestrini. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Camila Fonseca Netto, Carolina Pellegrini Barbosa Gracitelli, Heloisa Russ Giacometti, Nubia Vanessa dos Anjos Lima, Heloisa Andrade Maestrini. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Camila Fonseca Netto, Carolina Pellegrini Barbosa Gracitelli, Heloisa Russ Giacometti, Nubia Vanessa dos Anjos Lima, Heloisa Andrade Maestrini. Statistical analysis: not applicable. Obtaining funding: not applicable. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Heloisa Russ Giacometti, Nubia Vanessa dos Anjos Lima, Heloisa Andrade Maestrini. Research group leadership: Heloisa Andrade Maestrini.

REFERENCES

1. Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081-90.

2. Yoshida M, Okada E, Mizuki N, Kokaze A, Sekine Y, Onari K, et al. Age-specific prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and its relationship to refraction among more than 60,000 asymptomatic Japanese subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(11):1151-8.

3. Razeghinejad MR, Tania Tai TY, Fudemberg SJ, Katz LJ. Pregnancy and glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(4):324-35.

4. Vaideanu D, Fraser S. Glaucoma management in pregnancy: a questionnaire survey. Eye (Lond). 2007;21(3):341-3.

5. Sunness JS. The pregnant woman's eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988; 32(4):219-38.

6. Brauner SC, Chen TC, Hutchinson BT, Chang MA, Pasquale LR, Grosskreutz CL. The course of glaucoma during pregnancy: a retrospective case series. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(8):1089-94.

7. Mendez-Hernandez C, Garcia-Feijoo J, Saenz-Frances F, Santos-Bueso E, Martinez-de-la-Casa JM, Megias AV, et al. Topical intraocular pressure therapy effects on pregnancy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:1629-32.

8. Mathew S, Harris A, Ridenour CM, Wirostko BM, Burgett KM, Scripture MD, et al. Management of Glaucoma in Pregnancy. J Glaucoma. 2019;28(10):937-44.

9. Hashimoto Y, Michihata N, Yamana H, Shigemi D, Morita K, Matsui H, et al. Intraocular pressure-lowering medications during pregnancy and risk of neonatal adverse outcomes: a propensity score analysis using a large database. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105(10):1390-4.

10. Strelow B, Fleischman D. Glaucoma in pregnancy: an update. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2020;31(2):114-22.

11. Salim S. Glaucoma in pregnancy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(2):93-7.

12. Kumari R, Saha BC, Onkar A, Ambasta A, Kumari A. Management of glaucoma in pregnancy - balancing safety with efficacy. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2021; 13:25158414211022876.

13. Marx-Gross S, Laubert-Reh D, Schneider A, Höhn R, Mirshahi A, Münzel T, et al. The Prevalence of Glaucoma in Young People. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(12):204-10.

14. Coppens G, Stalmans I, Zeyen T. Glaucoma medication during pregnancy and nursing. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2010:(314):33-6.

15. Putterman GJ, Davidson J, Albert J. Lack of metabolism of timolol by ocular tissues. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1985;1(3):287-96.

16. Lustgarten JS, Podos SM. Topical timolol and the nursing mother. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101(9):1381-2.

17. Urtti A, Salminen L. Minimizing systemic absorption of topically administered ophthalmic drugs. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;37(6): 435-56.

18. Razeghinejad MR. Glaucoma medications in pregnancy. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2018;11(3):195-9.

19. Zimmerman TJ, Kooner KS, Kandarakis AS, Ziegler LP. Improving the therapeutic index of topically applied ocular drugs. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(4):551-3.

20. Sethi HS, Naik M, Gupta VS. Management of glaucoma in pregnancy: risks or choices, a dilemma? Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9(11):1684-90.

21. Weinreb RN, Papadopoulos M, Araie M, Susanna R, Goldberg I, Clive Migdal C, et al. Medical treatment of glaucoma: the 7th Consensus Report of the World Glaucoma Association. Fort Lauderdale; 2010.

22. Samra KA. The eye and visual system in pregnancy, what to expect? An in-depth review. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2013;6(2):87-91.

23. Kump LI, Cervantes-Castañeda RA, Androudi SN, Foster CS, Christen WG. Patterns of exacerbations of chronic non-infectious uveitis in pregnancy and puerperium. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2006;14(2):99-104.

24. Qureshi IA, Xi XR, Yaqob T. The ocular hypotensive effect of late pregnancy is higher in multigravidae than in primigravidae. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238(1):64-7.

25. Akar Y, Yucel I, Akar ME, Zorlu G, Ari ES. Effect of pregnancy on intraobserver and intertechnique agreement in intraocular pressure measurements. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219(1):36-42.

26. Horven I, Gjonnaess H. Corneal indentation pulse and intraocular pressure in pregnancy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;91(2):92-8.

27. Ebeigbe JA, Ebeigbe PN, Ighoroje AD. Intraocular pressure in pregnant and non-pregnant Nigerian women. Afr J Reprod Health. 2011;15(4):20-3.

28. Green K, Phillips CI, Cheeks L, Slagle T. Aqueous humor flow rate and intraocular pressure during and after pregnancy. Ophthalmic Res. 1988;20(6):353-7.

29. Tehrani S. Gender difference in the pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma. Curr Eye Res. 2015;40(2):191-200.

30. Cantor LB, Harris A, Harris M. Glaucoma medications in pregnancy. Rev Ophthalmol. 2000.p.91-9.

31. Chawla S, Chaudhary T, Aggarwal S, Maiti GD, Jaiswal K, Yadav J. Ophthalmic considerations in pregnancy. Med J Armed Forces India. 2013;69(3):278-84.

32. Qureshi IA, Xi XR, Wu XD, Pasha N, Huang YB. Effect of third trimester of pregnancy on diurnal variation of ocular pressure. Chin Med Sci J. 1997;12(4):240-3.

33. Riss B, Riss P. Corneal sensitivity in pregnancy. Ophthalmologica. 1981;183(2):57-62.

34. Millodot M. The influence of pregnancy on the sensitivity of the cornea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61(10):646-9.

35. Ding C, Chang N, Fong YC, Wang Y, Trousdale MD, Mircheff AK, et al. Interacting influences of pregnancy and corneal injury on rabbit lacrimal gland immunoarchitecture and function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(4):1368-75.

36. Weinreb RN, Lu A, Beeson C. Maternal corneal thickness during pregnancy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;105(3):258-60.

37. Park SB, Lindahl KJ, Temnycky GO, Aquavella JV. The effect of pregnancy on corneal curvature. CLAO J. 1992;18(4):256-9.

38. Grieshaber MC, Flammer J. Blood flow in glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2005;16(2):79-83.

39. Centofanti M, Manni GL, Migliardi R, Zarfati D, Lorenzano D, Scipioni M, et al. Influence of pregnancy on ocular blood flow. Acta Ophthalmol Scand Suppl. 2002;236:52-3.

40. Centofanti M, Migliardi R, Bonini S, Manni G, Bucci MG, Pesavento CB, et al. Pulsatile ocular blood flow during pregnancy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2002;12(4):276-80.

41. Akar Y, Yucel I, Akar ME, Uner M, Trak B. Long-term fluctuation of retinal sensitivity during pregnancy. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005; 40(4):487-91.

42. Dinç H, Esen F, Demirci A, Sari A, Resit Gümele H. Pituitary dimensions and volume measurements in pregnancy and post partum. MR assessment. Acta Radiol. 1998;39(1):64-9.

43. Socha MW, Piotrowiak I, Jagielska I, Kazdepka-Ziemińska A, Szymański M, Duczmal M, et al. [Retrospective analysis of ocular disorders and frequency of cesarean sections for ocular indications in 2000-2008 - our own experience]. Ginekol Pol. 2010;81(3):188-91.

44. Avasthi P, Sethi P, Mithal S. Effect of pregnancy and labor on intraocular pressure. Int Surg. 1976;61(2):82-4.

45. Meshi A, Armarnik S, Mimouni M, Segev F, Segal O, Kaneti H, et al. The effect of labor on the intraocular pressure in healthy women. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(1):59-64.

46. Kalogeropoulos D, Sung VC, Paschopoulos M, Moschos MM, Panidis P, Kalogeropoulos C. The physiologic and pathologic effects of pregnancy on the human visual system. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;39(8):1037-48.

47. Bito LZ. Impact of intraocular pressure on venous outflow from the globe: a hypothesis regarding IOP-dependent vascular damage in normal-tension and hypertensive glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 1996;5(2):127-34.

48. Costa VP, Arcieri ES, Harris A. Blood pressure and glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(10):1276-82.

49. Mohammadi SF, Letafat-Nejad M, Ashrafi E, Delshad-Aghdam H. A survey of ophthalmologists and gynecologists regarding termination of pregnancy and choice of delivery mode in the presence of eye diseases. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2017;29(2):126-32.

50. Danishevski K, McKee M, Sassi F, Maltcev V. The decision to perform Caesarean section in Russia. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(2):88-94.

51. Wielgos M, Bomba-Opoń D, Breborowicz GH, Czajkowski K, Debski R, Leszczynska-Gorzelak B, et al. Recommendations of the Polish Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians regarding caesarean sections. Ginekol Pol. 2018;89(11):644-57.

52. Law R, Bozzo P, Koren G, Einarson A. FDA pregnancy risk categories and the CPS: do they help or are they a hindrance? Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(3):239-41.

53. Coroi MC, Bungau S, Tit M. Preservatives from the eye drops and the ocular surface. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2015;59(1):2-5.

54. Samuelsson B, Goldyne M, Granström E, Hamberg M, Hammarström S, Malmsten C. Prostaglandins and thromboxanes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1978;47(1):997-1029.

55. Pellegrino M, D'Oria L, De Luca C, Chiaradia G, Licameli A, Neri C, et al. Glaucoma drug therapy in pregnancy: literature review and Teratology Information Service (TIS) Case Series. Curr Drug Saf. 2018;13(1):3-11.

56. da Silva Dal Pizzol T, Knop FP, Mengue SS. Prenatal exposure to misoprostol and congenital anomalies: systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol. 2006;22(4):666-71.

57. Clinical Review Report: Latanoprostene Bunod (Vyzulta): (Bausch Health, Canada Inc): Indication: For the reduction of intraocular pressure (IOP) in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Ottawa (ON); 2019.

58. Maul H, Longo M, Saade GR, Garfield RE. Nitric oxide and its role during pregnancy: from ovulation to delivery. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9(5):359-80.

59. Ersbøll AS, Hedegaard M, Søndergaard L, Ersbøll M, Johansen M. Treatment with oral beta-blockers during pregnancy complicated by maternal heart disease increases the risk of fetal growth restriction. BJOG. 2014;121(5):618-26.

60. Safran MJ, Robin AL, Pollack IP. Argon laser trabeculoplasty in younger patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97(3):292-5.

61. Wagenvoort AM, van Vugt JM, Sobotka M, van Geijn HP. Topical timolol therapy in pregnancy: is it safe for the fetus? Teratology. 1998;58(6):258-62.

62. Madadi P, Koren G, Freeman DJ, Oertel R, Campbell RJ, Trope GE. Timolol concentrations in breast milk of a woman treated for glaucoma: calculation of neonatal exposure. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(4):329-31.

63. Keränen A, Nykänen S, Taskinen J. Pharmacokinetics and side-effects of clonidine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1978;13(2):97-101.

64. Hoffmanová I, Sánchez D. Metabolic acidosis and anaemia associated with dorzolamide in a patient with impaired renal function. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(4):796-9.

65. Falardeau J, Lobb BM, Golden S, Maxfield SD, Tanne E. The use of acetazolamide during pregnancy in intracranial hypertension patients. J Neuroophthalmol. 2013;33(1):9-12.

66. Söderman P, Hartvig P, Fagerlund C. Acetazolamide excretion into human breast milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;17(5):599-600.

67. Rama Sastry BV, Olubadewo J, Harbison RD, Schmidt DE. Human placental cholinergic system. Occurrence, distribution and variation with gestational age of acetylcholine in human placenta. Biochem Pharmacol. 1976 Feb;25(4):425-31.

68. Kooner KS, Zimmerman TJ. Antiglaucoma therapy during pregnancy - part II. Ann Ophthalmol. 1988;20(6):208-11.

69. Tahara M, Kawagishi R, Sawada K, Morishige K, Sakata M, Tasaka K, et al. Tocolytic effect of a Rho-kinase inhibitor in a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide-induced preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(3):903-8.

70. Ergul M, Turgut NH, Sarac B, Altun A, Yildirim Ş, Bagcivan I. Investigating the effects of the Rho-kinase enzyme inhibitors AS1892802 and fasudil hydrochloride on the contractions of isolated pregnant rat myometrium. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;202:45-50.

71. Netland P. Glaucoma medical therapy: principles and management. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 33-155.

72. Drake SC, Vajaranant TS. Evidence-based approaches to glaucoma management during pregnancy and lactation. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2016;4(4):198-205.

73. Vyborny P, Sicakova S, Florova Z, Sovakova I. [Selective laser trabeculoplasty - implication for medicament glaucoma treatment interruption in pregnant and breastfeeding women]. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 73:61-3. Czech.

74. Mazze RI, Källén B. Reproductive outcome after anesthesia and operation during pregnancy: a registry study of 5405 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161(5):1178-85.

75. Shammas HJ, Milkie M, Yeo R. Topical and subconjunctival anesthesia for phacoemulsification: prospective study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997;23(10):1577-80.

76. Razeghinejad MR, Masoumpour M, Eghbal MH, Myers JS, Moster MR. Glaucoma surgery in pregnancy: a case series and literature review. Iran J Med Sci. 2016;41(5):437-45.

77. Pitukcheewanont O, Tantisevi V, Chansangpetch S, Rojanapongpun P. Factors related to hypertensive phase after glaucoma drainage device implantation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:1479-86.

78. Chung CY, Kwok AK, Chung KL. Use of ophthalmic medications during pregnancy. Hong Kong Med J. 2004;10(3):191-5.

79. Peccatori FA, Giovannetti E, Pistilli B, Bellettini G, Codacci-Pisanelli G, Losekoot N, et al. "The only thing I know is that I know nothing": 5-fluorouracil in human milk. Ann Oncol. 2012; 23(2):543-4.

Submitted for publication:

March 13, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

September 12, 2025.

Research Availability Statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are already available.

Edited by:

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior Associate Editor: Jayter S. de Paula

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: HR has received support from Abbvie, Cristalia, Bausch & Lomb, Glaukos Corporation, and Iridex. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.