Iago Diógenes Azevedo Costa1; David Restrepo2,3; Lucas Zago Ribeiro1; Andre Kenzo Aragaki1; Fernando Korn Malerbi1; Caio Saito Regatieri1; Luis Filipe Nakayama1,3

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2025-0025

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: Diabetic retinopathy screening in low- and middle-income countries is limited by restricted access to specialized care. Portable retinal cameras offer a practical alternative; however, image quality – affected by mydriasis – directly influences the performance of artificial intelligence models. This study evaluated the effect of mydriasis on image gradability and AI-based diabetic retinopathy detection in real-world, resource-limited settings.

METHODS: The proportions of gradable images were compared between mydriatic and non-mydriatic groups. Generalized estimating equations were used to identify factors associated with image gradability, including age, sex, race, diabetes duration, and systemic hypertension. A ResNet-200d model was trained on the mobile Brazilian Ophthalmological dataset and externally validated on both mydriatic and non-mydriatic images. Model performance was evaluated using accuracy, F1 score, area under the curve, and confusion matrix metrics. Sensitivity differences were assessed using the McNemar test, and area under the curves were compared using DeLong's test. The Youden index was used to determine optimal classification thresholds. Agreement between macula- and disc-centered images was analyzed using Cohen's κ.

RESULTS: The mydriatic group demonstrated a higher proportion of gradable images compared with the non-mydriatic group (82.1% vs. 55.6%; p<0.001). In non-mydriatic images, lower gradability was associated with systemic hypertension, older age, male sex, and longer diabetes duration. The AI model achieved better performance in mydriatic images (accuracy, 85.15%; area under the curve, 0.94) than in non-mydriatic images (accuracy, 79.68%; area under the curve, 0.93). The McNemar test showed a significant difference in sensitivity (p=0.0001), whereas DeLong's test revealed no significant difference in area under the curve (p=0.4666). The Youden index indicated that optimal classification thresholds differed based on mydriasis status. Agreement between image fields was moderate to substantial and improved with mydriasis.

CONCLUSION: Mydriasis significantly improves image gradability and enhances AI performance in diabetic retinopathy screening. Nonetheless, in low- and middle-income countries where pharmacologic dilation may be impractical, optimizing model calibration and thresholding for non-mydriatic images is essential to ensure effective AI implementation in real-world clinical environments.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence; Bias; Diabetic retinopathy; Portable camera; Retina

INTRODUCTION

The global rise in retinal diseases, particularly diabetic retinopathy (DR), underscores the urgent need for effective screening and diagnostic tools, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)(1,2). In these regions, access to specialized ophthalmic care is often limited, leading to delayed diagnoses, disease progression, and poorer visual outcomes(1). Portable retinal fundus cameras have emerged as a key solution, providing a cost-effective means to expand access to retinal imaging, particularly in remote or underserved areas(3–5). These devices offer a practical alternative to conventional tabletop cameras, enabling retinal image acquisition in non-clinical or community settings(3).

A crucial factor affecting the quality of retinal images is whether pupil dilation (mydriasis) is performed(6). Pharmacological mydriasis provides a wider and clearer retinal view, facilitating the detection of subtle retinal changes essential for the early diagnosis and management of conditions such as DR(6). Conversely, non-mydriatic imaging – while more convenient and comfortable for patients – may compromise image quality, especially in individuals with darker irides or under suboptimal lighting conditions(7). Furthermore, mydriatic eyedrop administration requires trained personnel capable of managing potential adverse reactions.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into DR screening has shown considerable promise, with AI models capable of identifying disease patterns in retinal images, thereby streamlining diagnosis and reducing the burden on ophthalmologists(8,9). However, the quality of the images used to train and validate these AI systems remains critical to diagnostic accuracy(10). Importantly, the presence or absence of mydriasis can significantly influence image clarity and, consequently, the performance of AI-based diagnostic tools used with portable cameras.

This study investigates the effect of mydriasis on image gradability and explores factors associated with reduced image quality. It further examines how mydriasis influences the diagnostic performance of AI models for DR screening. By comparing results between mydriatic and non-mydriatic images, this study aims to elucidate how pupil dilation affects the reliability of AI-based DR detection, particularly in resource-limited environments where portable fundus cameras are increasingly employed.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP; CAAE 33842220.7.0000.5505). Patients included in the study underwent retinal imaging before and after pharmacological mydriasis with 0.5% tropicamide eyedrops. The imaging protocol consisted of two images per eye – one macula-centered and one optic disc-centered – captured by trained healthcare professionals, including ophthalmic technicians and certified ophthalmologists. Data on age, gender, self-reported race, and clinical comorbidities were collected for analysis.

Two masked, certified ophthalmologists independently graded all images. In cases of disagreement, a third senior retinal specialist provided adjudication. Diabetic retinal lesions – including hemorrhages, microaneurysms, venous beading, intraretinal microvascular abnormalities, neovascularization, vitreous or preretinal hemorrhage, and tractional retinal membranes – were evaluated according to the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy (ICDR) classification(11).

For image gradability assessment, images were deemed gradable when at least two-thirds of the retina was visible and image focus was sufficient to visualize third-order vessels. To evaluate consistency in gradability between macula- and disc-centered images from the same eye, Cohen's κ coefficient was calculated separately for each mydriasis condition. Images were grouped by patient and eye, and only cases with both macula- and disc-centered images available were included in the analysis. Agreement was computed independently within the mydriatic and non-mydriatic groups.

Device description

The Phelcom Eyer (Phelcom Technologies, LLC, Boston, Massachusetts) is a portable retinal camera that integrates with a Samsung Galaxy S10 smartphone operating on Android 11. The device captures high-resolution retinal images suitable for DR screening. It features a 12-megapixel sensor that produces images with a resolution of 1600 × 1600 pixels, providing detailed retinal visualization. The camera's 45º field of view supports wide-angle fundus photography, essential for comprehensive retinal evaluation. The Eyer also includes an autofocus range of −20 to +20 diopters, ensuring accurate focus across varying refractive states. The device can be used for handheld capture or mounted on a slit lamp for stabilized imaging.

AI algorithm

A convolutional neural network pre-trained on ImageNet was used for DR classification. The model was trained on the mobile Brazilian Ophthalmological dataset (mBRSET)(13) and validated on the study dataset.

Each image was labeled as either "normal" or "DR" according to the ICDR scale(11). Preprocessing steps included resizing to 224 × 224 pixels and normalization using standard ImageNet parameters. Data augmentation was applied to enhance model robustness, incorporating random horizontal flips and rotations of up to 3º. Vertical flips, brightness changes, and random cropping were not used.

mBRSET dataset

The mBRSET, collected during the Itabuna Diabetes Campaign in Bahia, Brazil, included 1,291 patients and 5,164 retinal fundus images obtained after pharmacological mydriasis using the Phelcom Eyer device(12). The dataset comprises participants from diverse ethnic backgrounds, reflecting Bahia's mixed European, African, and Native American ancestry. The mean patient age was 61.4 yr (SD, 11.6), 65.1% were female, and 23.2% of the examinations were positive for DR(12).

Model training and validation

The ResNet-200d architecture was fine-tuned for binary classification (normal vs. DR) using cross-entropy loss and optimized with the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate = 1 × 10-4; weight decay = 1 × 10-4). A learning rate scheduler reduced the rate by a factor of 0.1 after three epochs of plateauing validation loss. The dataset was split 80/20 for training and testing at the patient level to prevent data leakage and ensure model generalizability. Training proceeded for 50 epochs with a batch size of 4, and early stopping (patience = 10 epochs) was used to prevent overfitting.

Performance metrics – including accuracy, F1 score, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), and confusion matrices – were calculated for each subgroup (mydriatic vs. non-mydriatic).

Performance evaluation and subgroup analysis

To determine the effect of demographic and clinical variables on image gradability in the non-mydriatic group, both univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) with an exchangeable working correlation structure, accounting for clustering of multiple images per patient. The binary outcome variable was image gradability, with covariates including age, gender, race, body mass index, diabetes duration, and systemic hypertension. All covariates were simultaneously included in the multivariate model to identify independent predictors.

A McNemar test was applied to determine whether statistically significant differences existed in sensitivity between the mydriatic and non-mydriatic groups, accounting for the paired nature of the data. Additionally, DeLong's test was used to compare the AUCs between the two groups. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

AI model performance in detecting DR was evaluated for paired gradable images under both imaging conditions. Metrics such as accuracy, F1 score, AUC, and confusion matrix elements (true positives [TP], false positives [FP], true negatives [TN], and false negatives [FN]) were compared between groups.

To explore optimal diagnostic performance across imaging conditions, the Youden index was calculated for each group to identify thresholds maximizing the sum of sensitivity and specificity. These optimized thresholds were used to derive additional diagnostic parameters and assess whether model calibration improved subgroup performance.

RESULTS

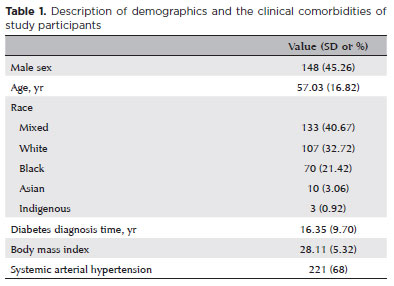

A total of 327 patients were included in the analysis, with a mean age of 57.03 yr (SD, 16.82; range, 9–90 yr); 45.26% were male. In total, 1,755 retinal fundus images were analyzed, corresponding to 414 non-mydriatic and 557 mydriatic eyes. In the non-mydriatic group, 248 patients were included, of whom 82 (33.1%) had one eye imaged and 166 (66.9%) had both eyes captured. In the mydriatic group, 310 patients were included, with 63 (20.3%) imaged in one eye and 247 (79.7%) in both eyes. Baseline demographics and comorbidities are summarized in Table 1. At the patient level, 44% had no signs of retinopathy, 26.47% were diagnosed with non-proliferative DR, and 29.31% had proliferative DR.

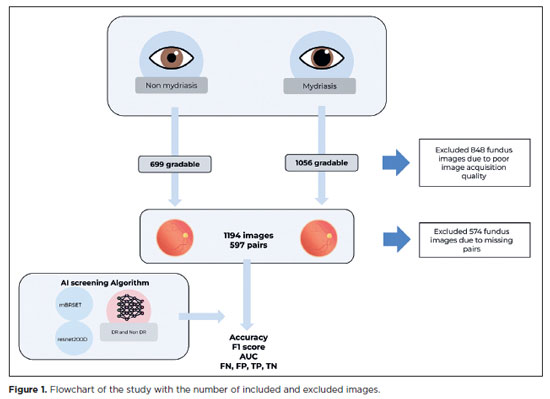

In the mydriatic group, 1,056 images (82.1%) were deemed gradable, compared with 699 images (55.6%) in the non-mydriatic group – a statistically significant difference (p<0.001; Figure 1). Cohen's κ analysis revealed moderate to substantial agreement between macula- and disc-centered images within the same eye. Agreement was moderate in the non-mydriatic group (κ=0.5917) and slightly higher in the mydriatic group (κ=0.6465), indicating improved consistency in gradability assessments with pharmacologic dilation.

In the non-mydriatic group, univariate GEE regression identified systemic hypertension, age, diabetes duration, male gender, and indigenous race as factors significantly associated with reduced image gradability. Systemic hypertension had the strongest effect, with hypertensive patients exhibiting approximately 50% lower odds of gradable images compared with non-hypertensive patients (odds ratio [OR]=0.50; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.34–0.74; p=0.0005). Increasing age also significantly reduced image gradability (OR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.49–0.71; p<0.0001). Similarly, longer diabetes duration was associated with decreased image quality (OR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.63–0.90; p=0.0016). Male gender was also a significant predictor, associated with lower odds of high-quality images than female gender (OR=0.61; 95% CI, 0.43–0.87; p=0.0067).

Regarding race, Indigenous participants were significantly more likely to have ungradable images (OR=0.27; 95% CI, 0.08–0.95; p=0.0416), whereas Black, Mixed, and White participants showed no significant association with image quality.

In the multivariate GEE model, only age, diabetes duration, and male gender remained independently associated with image gradability. Age continued to be a strong predictor, with 35% lower odds of gradable images (OR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.52–0.82; p=0.0003). Diabetes duration also remained significant (OR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.68–0.99; p=0.0376), as did male gender (OR=0.56; 95% CI, 0.39–0.81; p=0.0020). Systemic hypertension lost significance after adjustment (OR=0.83; 95% CI, 0.52–1.33; p=0.4377). None of the race categories remained statistically significant in the multivariate model, although indigenous participants still showed a non-significant trend toward lower image quality (OR=0.31; 95% CI, 0.06–1.55; p=0.155, Table 2).

Artificial intelligence

The baseline classification model achieved an accuracy of 83.03%, an F1 score of 0.83, and an AUC of 0.93 on the mBRSET testing subset using a threshold of 0.5.

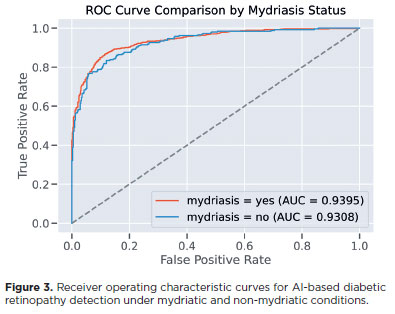

In the study dataset, after image quality screening, 1,194 images were included, comprising 597 pairs of non-mydriatic and mydriatic images. In the mydriatic group, model accuracy for detecting DR was 85.15%, compared with 79.68% in the non-mydriatic group. The F1 score and AUC were also higher in the mydriatic group (F1=0.86, AUC=0.94) than in the non-mydriatic group (F1=0.78, AUC=0.93; Figure 3).

The mydriatic group had fewer false positives (108, 18.1%) compared with the non-mydriatic group (120, 20.1%). However, the mydriatic group had a higher number of false negatives (53, 8.9%) than the non-mydriatic group (19, 3.2%; Figure 2). The lower false positive rate in the mydriatic group indicates that the model was less likely to incorrectly identify DR in patients without the disease when mydriasis was applied.

The McNemar test demonstrated a statistically significant difference in sensitivity between the two groups (p=0.0001), confirming that image gradability and classification performance were influenced by mydriasis. Conversely, DeLong's test for AUC comparison showed no significant difference (p=0.4666), indicating that the overall discriminative capacity of the model was similar regardless of dilation status.

To further explore the discrepancy between sensitivity and AUC results, the optimal threshold for each group was calculated using the Youden index. The optimal threshold for the mydriatic group was 0.859, corresponding to a sensitivity of 86.85% and specificity of 88.42%. For the non-mydriatic group, the optimal threshold was higher (0.948), yielding a sensitivity of 83.40% and specificity of 88.00%. These results suggest that while the model consistently ranked disease likelihood across both conditions, the optimal operating point varied depending on the presence of mydriasis.

DISCUSSION

DR is a global health challenge, with an increasing prevalence, particularly in LMICs(13). For DR screening programs, the use of non-mydriatic photography can be more pragmatic, yielding comparable results for detecting referable cases(6). This approach is particularly advantageous in resource-limited settings, where healthcare professionals may not always be available to administer mydriatic eye drops and where managing rare but potentially adverse reactions to these agents can pose additional challenges(9). Previous studies have reported 19.7%(14) and 26%(15) rates of ungradable images using tabletop cameras. However, our study found a higher rate of ungradable images (44.4%) when using a portable camera for non-mydriatic imaging.

Our results demonstrate a moderate to substantial agreement in image gradability between macula- and disc-centered fundus images from the same eye, with greater concordance observed under mydriatic conditions. This finding suggests that pharmacological dilation enhances consistency across different fields of view. Nevertheless, as macula- and disc-centered images evaluate distinct anatomical regions and are affected by different artifacts, perfect concordance is not expected. Some variability in quality assessment is inherent to this dual-field imaging strategy. These findings reinforce the importance of evaluating each image independently and support the inclusion of both views in screening protocols to maximize diagnostic coverage.

Consistent with previous reports, our study confirmed that older age is associated with reduced image quality(16). Additionally, significant associations were found between poor image quality and male gender, systemic hypertension, and longer duration of diabetes mellitus. In the univariate GEE analysis, all these factors were associated with a decreased likelihood of obtaining gradable retinal images, with systemic hypertension showing the strongest effect, followed by age, diabetes duration, and male gender. After adjusting for covariates in the multivariate GEE model, only age, diabetes duration, and male gender remained statistically significant. The effect of systemic hypertension was no longer significant, suggesting that its initial association may have been confounded by other clinical factors.

While portable cameras are gaining popularity in LMICs due to their affordability and ease of use(4,12), they generally produce lower-quality images than tabletop cameras. Automated DR screening represents a promising solution for such environments; however, image quality remains a key determinant of model performance in clinical deployment. Non-mydriatic images from portable cameras are more prone to artifacts and poor illumination, which may compromise automated screening accuracy.

The findings of this study highlight the effect of mydriasis on image quality and AI-based DR detection. In the mydriatic group, the model achieved higher accuracy, F1 score, and AUC compared with the non-mydriatic group, suggesting that pupil dilation enhances model performance. Furthermore, the mydriatic group exhibited fewer false positives, indicating a lower likelihood of incorrectly identifying DR in patients without disease.

The McNemar test confirmed a statistically significant difference in sensitivity between the two groups, demonstrating that mydriasis improves the model's ability to detect true positive cases. In contrast, the DeLong test showed no significant difference in AUC, indicating that the model's overall discriminative capacity remained stable regardless of mydriasis. Using the Youden index, optimal thresholds differed between groups, suggesting that while the model consistently ranks disease likelihood, its classification cutoff should be calibrated according to imaging conditions. Such calibration may enhance model performance in varied real-world scenarios.

These results underscore the benefits of mydriasis in improving image quality and diagnostic accuracy, particularly in settings where high-quality images are critical for early DR detection. The lower false positive rate in the mydriatic group implies that pupil dilation may reduce overdiagnosis, thereby increasing screening specificity.

In LMICs, where access to follow-up care is often limited, reducing false positives could minimize unnecessary referrals and improve the cost-effectiveness of AI-based screening programs. However, the variable availability of mydriatic agents in LMICs poses challenges, as dilation may not always be feasible due to cost, patient discomfort, or limited access to pharmacological agents. In such contexts, non-mydriatic imaging remains essential despite its limitations, though it may affect the consistency and generalizability of AI screening outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, a learning curve is associated with image acquisition using handheld cameras. Although the healthcare professionals involved were experienced with the device, they were not retinal imaging specialists, which could have influenced image quality. Second, focusing solely on paired images introduces selection bias and may not fully represent the variability in non-mydriatic image quality. This reduced sample size may also affect performance comparisons between groups. Third, the generalizability of the results is limited by the use of a single dataset and camera model, which may not reflect other devices or protocols. Additionally, the analysis combined referral categories, preventing assessment of the model's accuracy across specific DR severity levels. Finally, data augmentation techniques simulating variations in illumination and contrast were not applied, which could have improved robustness – particularly for non-mydriatic images. Future research should validate these findings across larger and more diverse datasets, incorporating multiple devices and data augmentation strategies to enhance model generalizability.

Overall, this study underscores the importance of optimizing AI models for varying imaging conditions. While mydriasis improves image quality and performance, further refinement is needed to reduce false positives and negatives, especially in resource-limited environments. Future work should focus on enhancing algorithms for non-mydriatic images – through improved preprocessing, adaptive thresholding, or models specifically trained for lower-quality input – to support broader and more equitable implementation of AI-driven DR screening.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS:

Significant contribution to conception and design: Iago Diogenes, David Restrepo, Lucas Zago Ribeiro; Andre Kenzo Aragaki, Fernando Korn Malerbi, Caio Saito Regatieri, Luis Filipe Nakayama. Data acquisition: Iago Diogenes. Data analysis and interpretation: Iago Diogenes, David Restrepo, Luis Filipe Nakayama. Manuscript drafting: Iago Diogenes, David Restrepo, Lucas Zago Ribeiro, Andre Kenzo Aragaki, Fernando Korn Malerbi, Caio Saito Regatieri, Luis Filipe Nakayama. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Iago Diogenes, David Restrepo, Lucas Zago Ribeiro, Andre Kenzo Aragaki, Fernando Korn Malerbi, Caio Saito Regatieri, Luis Filipe Nakayama. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Iago Diogenes, David Restrepo, Lucas Zago Ribeiro, Andre Kenzo Aragaki, Fernando Korn Malerbi, Caio Saito Regatieri, Luis Filipe Nakayama. Statistical analysis: Luis Filipe Nakayama. Obtaining funding: not applicable. Supervision administrative, technical, or material support: Luis Filipe Nakayama, Fernando Korn Malerbi, Caio Saito Regatieri. Research group leadership: Luis Filipe Nakayama, Fernando Korn Malerbi, Caio Saito Regatieri.

REFERENCES

1. Yim D, Chandra S, Sondh R, Thottarath S, Sivaprasad S. Barriers in establishing systematic diabetic retinopathy screening through telemedicine in low- and middle-income countries. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(11):2987-92.

2. Magliano D, Boyko EJ. Diabetes atlas. International Diabetes Federation; 2021. Available from: https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=OG6IzwEACAAJ

3. de Oliveira JA, Nakayama LF, Zago Ribeiro L, de Oliveira TV, Choi SN, Neto EM, et al. Clinical validation of a smartphone-based retinal camera for diabetic retinopathy screening. Acta Diabetol. 2023;60(8):1075-81.

4. Rajalakshmi R, Prathiba V, Arulmalar S, Usha M. Review of retinal cameras for global coverage of diabetic retinopathy screening. Eye (Lond). 2021;35(1):162-72.

5. Vujosevic S, Aldington SJ, Silva P, Hernández C, Scanlon P, Peto T, et al. Screening for diabetic retinopathy: new perspectives and challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(4):337-47.

6. Piyasena MM, Murthy GV, Yip JL, Gilbert C, Peto T, Gordon I, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy of detection of any level of diabetic retinopathy using digital retinal imaging. Syst Rev. 20187;7(1):182.

7. Banaee T, Ansari-Astaneh MR, Pourreza H, Faal Hosseini F, Vatanparast M, Shoeibi N, et al. Utility of 1% tropicamide in improving the quality of images for Tele-screening of diabetic retinopathy in patients with dark irides. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017;24(4):217-21.

8. Malerbi FK, Andrade RE, Morales PH, Stuchi JA, Lencione D, de Paulo JV, et al. Diabetic retinopathy screening using artificial intelligence and handheld smartphone-based retinal camera. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2022;16(3):716-23.

9. Sosale AR. Screening for diabetic retinopathy - is the use of artificial intelligence and cost-effective fundus imaging the answer? Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2019;39(1):1-3.

10. Nakayama LF, Matos J, Quion J, Novaes F, Mitchell WG, Mwavu R, et al. Unmasking biases and navigating pitfalls in the ophthalmic artificial intelligence lifecycle: A narrative review. PLOS Digit Health. 2024;3(10):e0000618.

11. Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL 3rd, Klein RE, Lee PP, Agardh CD, Davis M, et al.; Global Diabetic Retinopathy Project Group. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(9):1677-82.

12. Wu C, Restrepo D, Nakayama LF, Ribeiro LZ, Shuai Z, Barboza NS, et al. A portable retina fundus photos dataset for clinical, demographic, and diabetic retinopathy prediction. Sci Data. 2025;12(1):323.

13. Sivaprasad S, Pearce E. The unmet need for better risk stratification of non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabet Med. 2019;36(4):424-33.

14. Scanlon PH, Malhotra R, Thomas G, Foy C, Kirkpatrick JN, Lewis-Barned N, et al. The effectiveness of screening for diabetic retinopathy by digital imaging photography and technician ophthalmoscopy. Diabet Med. 2003;20(6):467-74.

15. Murgatroyd H, Ellingford A, Cox A, Binnie M, Ellis JD, MacEwen CJ, et al. Effect of mydriasis and different field strategies on digital image screening of diabetic eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(7):920-4.

16. Scanlon PH, Foy C, Malhotra R, Aldington SJ. The influence of age, duration of diabetes, cataract, and pupil size on image quality in digital photographic retinal screening. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(10):2448-53.

Submitted for publication:

January 27, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

October 8, 2025.

Approved by the following research ethics committee: Universidade Federal de São Paulo – UNIFESP (CAAE: 33842220.7.1001.5505).

Data Availability Statement: The datasets produced and/or analyzed in this study can be provided to referees upon request.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior

Associate Editor: Camila Koch

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.