Priscila Sánchez Moreno1; Aubert Quintanilla Rivera1; Mariana Badillo Fernández1; Jesús Martín Ayala Flores1; Van Charles Lansingh 1,2, 3,4,5; Van Nguyen6

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2024-0397

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness worldwide. When topical hypotensive agents or laser trabeculoplasty fail to adequately control the disease, escalation of therapy becomes necessary, with transscleral cyclophotocoagulation being one of the available options. Several variations of transscleral cyclophotocoagulation exist, including traditional continuous wave, MicroPulse, and slow-coagulation techniques. We propose a novel variation – custom slow-coagulation transscleral cyclophotocoagulation – which combines elements of both continuous wave and slow-coagulation approaches. This study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of this technique in patients with refractory glaucoma.

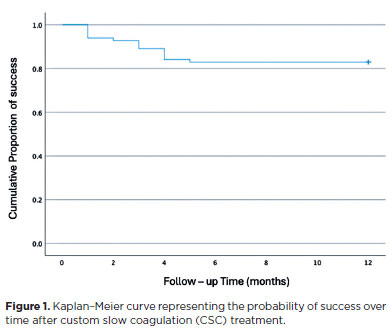

METHODS: This retrospective, interventional study included 104 eyes of 83 patients with refractory glaucoma who underwent custom slow-coagulation transscleral cyclophotocoagulation. Changes in intraocular pressure, visual acuity, the number of glaucoma medications, and postoperative complications were analyzed. A paired t test was used to compare changes in intraocular pressure and visual acuity, while the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to categorical variables. Success rates following custom slow-coagulation transscleral cyclophotocoagulation were estimated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis.

RESULTS: Mean intraocular pressure decreased significantly from 38.9 ± 15.8 mmHg at baseline to 16.3 ± 9.9 mmHg at Month 12 (p<0.001). The mean number of glaucoma medications also decreased significantly from 3.6 ± 0.6 to 1.8 ± 1.4 (p<0.001). No significant reduction in mean visual acuity was observed during follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS: Custom slow-coagulation transscleral cyclophotocoagulation effectively reduced baseline intraocular pressure and the number of glaucoma medications, with a low rate of complications and no decline in visual acuity over a 12-month follow-up period. This novel technique demonstrated a high safety profile in a Hispanic population and represents a low-cost, minimally invasive procedure with rapid recovery and promising efficacy in intraocular pressure control.

Keywords: Glaucoma/surgery; Sclera; Filtering surgery; Laser coagulation/methods; Lasers, semiconductor/therapeutic use; Intraocular pressure; Blindness/prevention & control; Vision, low/epidemiology; Visual acuity

INTRODUCTION

According to the Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study, glaucoma is the most common cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. In 2020, an estimated 3.61 million people were blind, and nearly 4.14 million had visual impairment due to glaucoma. Overall, glaucoma accounted for 8.39% of all blindness and 1.41% of all moderate-to-severe visual impairment(1). Treatment can slow or halt disease progression in most cases; therefore, early detection and management are essential(2).

Refractory glaucoma is defined as an intraocular pressure (IOP) that remains insufficiently controlled to prevent disease progression, despite maximum medical therapy and after the failure of one or more filtration procedures(3). When ocular hypotensive medications or laser trabeculoplasty are ineffective, traditional surgical options such as trabeculectomy or valved drainage implants are typically considered. However, these procedures have specific indications and carry potential complications, necessitating close postoperative monitoring.

Since the introduction of micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation (MP-TSCPC) in 2010, this approach has demonstrated greater selectivity and reduced collateral damage compared to continuous-wave TSCPC (CW-TSCPC)(4). However, MP-TSCPC is more costly and less accessible for low-resource institutions. The cost of an MP-TSCPC procedure in the United States ranges from 1,677 to 2,714 USD, whereas CW-TSCPC typically costs about half that amount. Consequently, CW-TSCPC remains the most widely used cyclodestructive technique(5).

Laser treatment is particularly useful for refractory glaucoma, as it can be employed in patients with prior surgeries or in those with limited surgical options due to conjunctival scarring. Furthermore, the procedure can be repeated when necessary.

Currently, two main techniques are used for delivering diode laser energy in CW-TSCPC: the traditional "pop" technique and the more recent slow-coagulation TSCPC (SC-TSCPC) technique introduced by Gaasterland in 2009. The conventional pop technique typically begins with a laser power of approximately 1,750–2,000 mW applied for 2 s. The power is gradually increased until an audible "pop" is heard – indicating a micro-explosion of uveal tissue – and then reduced until the popping ceases(6).

In contrast, the SC-TSCPC technique delivers a controlled 1,250 mW of power over 4 s, thereby minimizing collateral tissue damage and inflammation. This controlled ablation of the ciliary body leads to fewer complications while maintaining comparable efficacy to the traditional pop technique(6).

Few studies have examined the outcomes of TSCPC in Hispanic populations, with only one previous study specifically investigating CW-TSCPC in Mexican patients(7). This study aims to evaluate the success rate of a modified approach, termed custom slow coagulation TSCPC (CSC-TSCPC).

We hypothesize that patients with refractory glaucoma undergoing CSC-TSCPC will achieve significant IOP reduction, require fewer glaucoma medications, and maintain stable visual acuity (VA) after treatment.

METHODS

Study design

This retrospective interventional study was conducted at the Mexican Institute of Ophthalmology (IMO) in Querétaro and included patients with refractory glaucoma who underwent CSC-TSCPC between August 2018 and January 2022. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the IMO Institutional Review Board on August 14, 2022 (Approval No. 22-CEI-003-2016215).

Participants

CSC-TSCPC was offered to patients aged ≥18 yr with uncontrolled IOP and/or documented disease progression—confirmed by Humphrey visual field testing or optic nerve optical coherence tomography – despite maximally tolerated IOP-lowering medications. Additional inclusion criteria were (1) poor surgical candidacy (e.g., advanced age, lack of family support, or conjunctival scarring), (2) intolerance or nonadherence to medical therapy, or (3) deferral of incisional glaucoma surgery due to financial constraints.

Exclusion criteria included (1) painful blind eye (VA of no light perception [NLP] or light perception with pain), (2) previous cyclodestructive procedures, (3) any intraocular surgery within three months prior to CSC-TSCPC, or (4) <1 yr of postoperative follow-up.

Laser intervention

The diode laser used was the OcuLight SL (Iridex Corporation) with a wavelength of 810 nm in continuous-wave mode. The laser parameters were as follows: pulse duration of 4,000 ms, pulse interval of 1,000 ms, and initial power of 1,250 mW. Power was adjusted individually, increasing in 50 mW increments until an audible "pop" was heard, then reduced by 50 mW to maintain energy just below the pop threshold. The maximum power used was 1,450 mW.

Prior to the procedure, all patients received a peribulbar block with lidocaine and bupivacaine, along with sedation and anesthetic monitoring. The G-Probe (IRIDEX Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA) was positioned perpendicular to the limbus and aimed at the ciliary body (3 mm posterior to the limbus) under transillumination. The number of laser applications varied according to baseline IOP: <21 mmHg, 10 shots over 180º; 20–30 mmHg, 20 shots over 360º; 31–40 mmHg, 25 shots; 41–50 mmHg, 28 shots; and 50 mmHg, 30 shots over 360º.

In all cases, the 3 and 9 o'clock meridians were avoided to protect the long posterior ciliary nerves and vessels.

All laser interventions were performed by glaucoma specialists or ophthalmology residents under faculty supervision. Postoperative treatment included prednisolone acetate 1% four times daily (QID), atropine 1% twice daily (BID), ciprofloxacin QID, and oral analgesics as needed. Topical hypotensive medications were continued and adjusted according to IOP levels during follow-up.

Data collection and follow-up

Preoperative baseline data included age, sex, VA, preoperative IOP, glaucoma type, and the number of glaucoma medications. IOP was measured using Goldmann applanation tonometry, and VA was assessed using a Snellen chart and converted to logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) for statistical analysis. The severity of glaucomatous optic neuropathy was graded using the Hodapp–Parrish–Anderson staging system, based on preoperative visual field testing performed with a Humphrey Field Analyzer (Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc., Dublin, CA, USA).

After CSC-TSCPC, patients were evaluated at Week 1 and at Months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12. At each postoperative visit, VA, IOP, number of IOP-lowering medications, and complications were recorded.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the change in IOP after treatment and during the 12-month follow-up period. Secondary outcomes included changes in the number of IOP-lowering medications, VA, and the incidence of postoperative complications.

Success criteria

Treatment success was defined as a postoperative IOP between 6 and 21 mmHg, with at least a 20% reduction from baseline and no increase in glaucoma medications. Patients not meeting these criteria were classified as treatment failures but were retained in the analysis. Additionally, patients requiring retreatment were also considered treatment failures.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables. Paired t tests were used to compare changes in IOP and VA, while the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to categorical variables (e.g., number of medications). Logistic regression was used for binary outcomes (e.g., complications), incorporating variables such as eye laterality, year, sex, probe type, and glaucoma type.

The success rate of CSC-TSCPC was estimated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, and Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify predictors of treatment failure based on demographic and baseline factors associated with IOP reduction. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

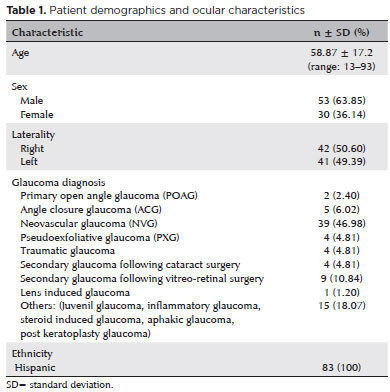

A total of 189 patients underwent CSC-TSCPC; however, 106 (56.1%) were excluded due to lack of follow-up. Ultimately, 104 eyes from 83 patients (49.3%) completed the 12-month follow-up. Demographic characteristics are summarized in table 1. The mean age was 58.87 ± 17.2 yr, and neovascular glaucoma (NVG) was the most common diagnosis. The main reasons for loss to follow-up were socioeconomic barriers and residence in remote areas.

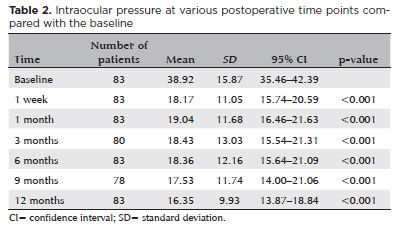

The trend in IOP over time is presented in table 2. The baseline mean IOP was 38.9 ± 15.8 mmHg, which significantly decreased to 18.1 ± 11.0 mmHg at Week 1 (53% reduction, p<0.001), 19.0 ± 11.6 mmHg at Month 1 (51% reduction, p<0.001), 18.4 ± 13.0 mmHg at Month 3 (53% reduction, p<0.001), 18.3 ± 12.1 mmHg at Month 6 (53% reduction, p<0.001), 17.5 ± 11.7 mmHg at Month 9 (55% reduction, p<0.001), and 16.3 ± 9.9 mmHg at Month 12 (58% reduction, p<0.001).

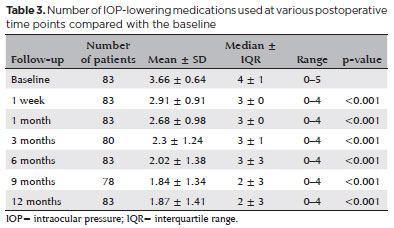

The number of glaucoma medications over time is shown in table 3. The mean number of medications significantly decreased from 3.6 ± 0.6 at baseline to 2.9 ± 0.9 (21% reduction, p<0.001) at Week 1; 2.6 ± 0.9 (27% reduction, p<0.001) at Month 1; 2.3 ± 1.2 (37% reduction, p<0.001) at Month 3; 2.0 ± 1.3 (45% reduction, p<0.001) at Month 6; and 1.8 ± 1.3 (50% reduction, p<0.001) at both Months 9 and 12. This represents an overall reduction of 21%–50% throughout follow-up.

The first medication discontinued was the oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. At baseline, 37 patients (44%) were using acetazolamide; all of them (100%) successfully discontinued it during follow-up, improving quality of life and minimizing both short- and long-term adverse effects.

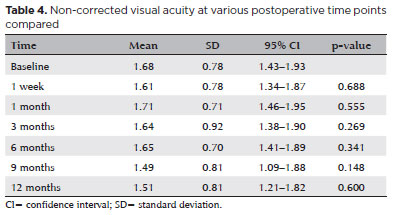

Baseline VA, converted to logMAR, ranged from NLP to 0.30. There were no statistically significant changes in mean VA compared with baseline at any follow-up point (Table 4).

The treatment success rate was 93.9% at Week 1, 92.7% at Month 1, 89.0% at Month 3, 84.1% at Month 6, 82.9% at Month 9, and 82.8% at Month 12. The cumulative probability of success after CSC-TSCPC is depicted in the Kaplan–Meier survival curve (Figure 1).

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses indicated that age, laterality, diagnosis, and baseline VA were not significantly associated with treatment failure (Tables 5 and 6). Baseline IOP, however, was significantly associated with success rate: for every 1 mmHg increase in baseline IOP, there was a 0.97 relative risk of treatment success (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.96–0.98; p<0.001). Furthermore, when categorizing baseline IOP, patients with IOP >30 mmHg had a 5.02 relative risk of treatment success (p<0.001).

During follow-up, seven adverse events (6.7%) were reported: six cases of transient hypotony (5.7%) within the first month, all of which resolved with topical corticosteroids, and one case of phthisis bulbi (0.96%) during the 12-month period.

DISCUSSION

Custom slow CSC-TSCPC is a non-invasive method with a high success rate and few complications, making it a suitable alternative for IOP control in refractory glaucoma cases since the introduction of CW-TSCPC by Gaasterland and Pollack in 1992(6). Recent advances in micropulse technology have provided alternative options for IOP control; however, these methods are often more expensive and less accessible in resource-limited settings.

In this study, we introduced a novel variation of the SC-TSCPC technique, in which an initial low energy of 1,250 mW was gradually increased in 50 mW increments until a "pop" was heard, followed by a 50 mW reduction until the pop ceased. Laser energy was maintained just below the pop threshold for each patient, with a maximum of 1,450 mW. This approach differs from SC-TSCPC by employing modulated rather than fixed energy levels.

In our study using CSC-TSCPC, IOP decreased by 51%–58% across various follow-up periods, with the greatest reduction observed at 12 months. These results align with previous reports indicating a global IOP reduction of at least 50% from baseline within the first year(8,9). Reported success rates vary globally due to differences in study design, follow-up duration, and success criteria. Studies with a 12-month follow-up that define success as IOP ≤21 mmHg without an increase in medication report rates ranging from 50% to 94.4% using CW-TSCPC(3,8,10–13). Parekh et al.(14) reported a 68.5% success rate with SC-TSCPC after 1 yr.

Our univariate and multivariate analyses showed that higher baseline IOP was associated with a greater hypotensive effect, consistent with Sarrafpour et al.(12). No other variable, including age, sex, diagnosis, or probe type, was significantly associated with the outcome.

Among our patients, 39.7% (n=33) were diagnosed with NVG, 69% of whom had baseline IOP >30 mmHg. Ishida(13), noted that this subgroup tends to have higher and more variable IOPs due to the inflammatory cascade involved in its pathogenesis. Although our Cox multivariate analysis found no correlation, our findings are consistent with those of Al Habash et al.(15), who studied predominantly NVG patients and observed higher success rates and IOP reduction in those with elevated baseline IOP.

A common concern following cyclodestructive procedures for refractory glaucoma is reduced VA. However, recent studies, including that by Dastiridou et al.(16), found no significant association between these procedures and postoperative visual loss, suggesting that outcomes are multifactorial. In our study, there was no statistically significant decrease in mean VA during follow-up, although one patient developed phthisis bulbi after radiotherapy.

Reported complications of CW-TSCPC and SC-TSCPC include pain, uveitis, IOP spikes, pigment dispersion(11), transient pupillary mydriasis, atonic pupil, hyphema, vitreous hemorrhage, cataract progression, lens subluxation, malignant glaucoma, necrotizing scleritis, vision loss, sympathetic ophthalmia[13,15], hypotony, and phthisis bulbi.

In our study, the rate of severe complications with CSC-TSCPC was low, with only one case of phthisis bulbi (1.2%), which is lower than the rates reported by Iliev and Gerber (9.9%), Murphy et al. (5.3%), Nabili and Kirkness (5.0%), and Goldenberg-Cohen et al. (3.1%)(17–20). Other studies have reported similar or lower rates, such as Gupta and Agarwal (1.9%), Mistlberger et al. (1.9%), and Leszczynski et al. (1.2%)(9,21,22). All these studies used the traditional pop technique.

The single case of phthisis bulbi in our study raises uncertainty regarding causality, as the patient had undergone multiple prior ocular interventions, including surgery for retinopathy of prematurity, cataract extraction, and IOL repositioning. CSC-TSCPC was performed for uncontrolled IOP (36 mmHg), which improved to 12 mmHg postoperatively. The patient later received 19 sessions of radiotherapy for a vasoproliferative tumor and was lost to follow-up. Three months after radiotherapy, the patient presented with hypotony and phthisis bulbi, suggesting a cumulative effect of prior treatments rather than direct CSC-TSCPC causation.

There were six cases (7.2%) of transient hypotony, all occurring within the first month and resolving with topical steroids. This rate is lower than that reported by Ramli et al. (39.0%), Nabili and Kirkness (25.0%), Iliev and Gerber (17.6%), Murphy et al. (9.5%), and Yildirim et al. (9.1%)(17–19,23,24)and comparable with those by Bezci Aygun et al. (6.6%) and Kosoko et al. (3.7%)(25,26). All of the above studies used the traditional pop technique. Duerr et al.(6) reported a 2% hypotony rate with SC-TSCPC. Our results differ from those of Iliev and Gerber(17), where higher rates of], who observed a 74% hypotony rate in NVG patients. In our study, no such association was found, despite NVG being the most common subtype.

Stevenson-Fernandez et al.(27) compared CW-TSCPC and SC-TSCPC, finding no statistically significant difference in IOP reduction but a higher complication rate in the CW-TSCPC group (13% vs. 0%). In a Hispanic population, a study conducted at the Institute of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Monterrey Institute of Technology, achieved a 73.6% success rate using fixed energy of 2,000 mW for 2 s, regardless of the presence of a pop. Hypotony (<5 mmHg) occurred in 26% of cases(7). Kaushik et al.(3), in an Asian cohort, found that patients with greater ocular pigmentation required less energy and had fewer complications compared with Caucasians. Similarly, Kosoko et al.(25) observed more audible pops in African American than Caucasian patients at the same energy level, while post-mortem data suggested that European patients may require 50% more energy(28). Animal studies support this correlation between pigmentation and laser response, with pigmented rabbits showing coagulative necrosis and albino rabbits showing none(29).

Greater ocular pigmentation may enhance treatment efficacy while reducing complications by requiring lower energy levels. We hypothesize that this relationship explains the lower complication rates observed in our population.

This study has several limitations. The most significant is the high loss to follow-up (56.08%), substantially higher than the 32% reported in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study, likely due to financial constraints. Limited resources in our population likely contributed to this higher attrition rate(30). Additional limitations include the retrospective, non-comparative design and variability in surgeon experience.

Furthermore, ocular pigmentation data were not included, limiting the assessment of its effect on outcomes. Future studies should incorporate this variable, along with stratified analyses of laser parameters and complications. Randomized controlled trials comparing CW-TSCPC, SC-TSCPC, MP-TSCPC, and CSC-TSCPC are also warranted to validate these findings.

In conclusion, our study in a Hispanic population supports global evidence that greater ocular pigmentation is associated with lower energy requirements and fewer complications such as hypotony. The findings indicate that CSC-TSCPC is an effective and safe technique for reducing baseline IOP and medication dependence, maintaining a low complication rate over a 12-month follow-up in patients with refractory glaucoma.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Significant contribution to conception and design: Mariana Badillo Fernández, Aubert Quintanilla Rivera, Jesús Martín Ayala Flores. Data acquisition: Priscila Sánchez Moreno. Data analysis and interpretation: Priscila Sánchez Moreno. Manuscript drafting: Priscila Sánchez Moreno, Aubert Quintanilla Rivera, Mariana Badillo Fernández. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Van Charles Lansingh, Van Nguyen. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Mariana Badillo Fernández, Aubert Quintanilla Rivera, Jesús Martín Ayala Flores, Priscila Sánchez Moreno, Van Charles Lansingh, Van Nguyen. Statistical analysis: Mariana Banuet (statistics expert). Obtaining funding: not applicable. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Mariana Badillo Fernández, Aubert Quintanilla Rivera. Research group leadership: Mariana Badillo Fernández.

REFERENCES

1. Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study; GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators. Global estimates on the number of people blind or visually impaired by glaucoma: A meta-analysis from 2000 to 2020. Eye (Lond). 2024; 38(11):2036-46.

2. GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the Right to Sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(2):e144-e160. Comment in: Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(2):e130-e143.

3. Kaushik S, Pandav SS, Jain R, Bansal S, Gupta A. Lower energy levels adequate for effective transcleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in Asian eyes with refractory glaucoma. Eye (Lond). 2008;22(3):398-405.

4. Grippo TM, Töteberg-Harms M, Giovingo M, Francis BA, de Crom RR, Jerkins B, et al. Evidence-Based consensus guidelines series for micropulse transscleral laser therapy - surgical technique, post-operative care, expected outcomes and retreatment/enhancements. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:71-83.

5. Abdelrahman AM, El Sayed YM. Micropulse versus continuous wave transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in refractory pediatric glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(10):900-5.

6. Duerr ER, Sayed MS, Moster SJ, Holley TD, Peiyao J, Vanner EA, et al. Transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation: a comparison of slow coagulation and standard coagulation techniques. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2018;1(2):115-22.

7. Espino-Barros-Paulau A, Rodríguez-Garcia A. Ciclofotocoagulación transescleral con láser de diodo en el manejo del glaucoma neovascular en pacientes diabéticos. Rev Mex Oftalmol. 2012;86(1):12-9.

8. Schlote T, Derse M, Rassmann K, Nicaeus T, Dietz K, Thiel HJ. Efficacy and safety of contact transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation for advanced glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2001;10(4):294-301.

9. Mistlberger A, Liebmann JM, Tschiderer H, Ritch R, Ruckhofer J, Grabner G. Diode laser transscleral cyclophotocoagulation for refractory glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2001;10(4):288-93.

10. Koraszewska-Matuszewska B, Leszczyński R, Samochowiec-Donocik E, Nawrocka LZ. [Cyclodestructive procedures in secondary glaucoma in children]. Klin Oczna. 2004;106(1-2 Suppl.):199-200. Polish.

11. Ansari E, Gandhewar J. Long-term efficacy and visual acuity following transscleral diode laser photocoagulation in cases of refractory and non-refractory glaucoma. Eye (Lond). 2007;21(7):936-40.

12. Sarrafpour S, Saleh D, Ayoub S, Radcliffe NM. Micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation: a look at long-term effectiveness and outcomes. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2019;2(3):167-71.

13. Ishida K. Update on results and complications of cyclophotocoagulation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24(2):102-10.

14. Parekh Z, Wang J, Qiu M. Outcomes of slow coagulation transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in a predominantly African American glaucoma population. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2024;35:102072.

15. Al Habash A, Alahmadi AS. Outcome Of MicroPulse® transscleral photocoagulation in different types of glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:2353-60.

16. Dastiridou AI, Katsanos A, Denis P, Francis BA, Mikropoulos DG, Teus MA, et al. Cyclodestructive procedures in glaucoma: a review of current and emerging options. Adv Ther. 2018;35(12):2103-27.

17. Iliev ME, Gerber S. Long ‐ term outcome of trans‐ scleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in refractory glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(12):1631-5.

18. Murphy CC, Burnett CA, Spry PG, Broadway DC, Diamond JP. A two centre study of the dose-response relation for transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in refractory glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(10):1252-7.

19. Nabili S, Kirkness CM. Trans-scleral diode laser cyclophoto-coagulation in the treatment of diabetic neovascular glaucoma. Eye (Lond). 2004;18(4):352-6.

20. Goldenberg-Cohen N, Bahar I, Ostashinski M, Lusky M, Weinberger D, Gaton DD. Cyclocryotherapy versus transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation for uncontrolled intraocular pressure. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2005;36(4):272-9.

21. Leszczynski R, Gierek-Lapinska A, Forminska-Kapuscik. M. Transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in the treatment of secondary glaucoma Med Sci Monit. 2004;10(9):CR542-8.

22. Gupta V, Agarwal HC. Contact trans-scleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation treatment for refractory glaucomas in the Indian population. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2000;48(4):295-300.

23. Yildirim N, Yalvac IS, Sahin A, Ozer A, Bozca T. A comparative study between diode laser cyclophotocoagulation and the Ahmed glaucoma valve implant in neovascular glaucoma: a long-term follow-up. J Glaucoma. 2009;18(3):192-6.

24. Ramli N, Htoon HM, Ho CL, Aung T, Perera S. Risk factors for hypotony after transscleral diode cyclophotocoagulation. J Glaucoma. 2012;21(3):169-73.

25. Kosoko O, Gaasterland DE, Pollack IP, Enger CL. Long-term outcome of initial ciliary ablation with contact diode laser transscleral cyclophotocoagulation for severe glaucoma. The Diode Laser Ciliary Ablation Study Group. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(8):1294-302. Comment in: Ophthalmology. 1997;104(2):171-3. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(4):568-70.

26. Bezci Aygün F, Mocan MC, Kocabeyoğlu S, İrkeç M. Efficacy of 180º cyclodiode transscleral photocoagulation for refractory glaucoma. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2018;48(6):299-303.

27. Stevenson-Fernandez MO, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Espino-Barros Palau A, Gonzalez-Madrigal PM. Efficacy and safety of pop-titrated versus fixed-energy trans-scleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation for refractory glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2019;39(3):513-9.

28. Coleman AL, Jampel HD, Javitt JC, Brown AE, Quigley HA. Transscleral cyclophotocoagulation of human autopsy and monkey eyes. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991;22(11):638-43.

29. Cantor LB, Nichols DA, Katz LJ, Moster MR, Poryzees E, Shields JA, et al. Neodymium-YAG transscleral cyclophotocoagulation. The role of pigmentation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30(8):1834-7.

30. Unzueta M, Globe D, Wu J, Paz S, Azen S, Varma R; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Compliance with recommendations for follow-up care in Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(2):285-91.

Submitted for publication:

January 30, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

September 12, 2025.

Approved by the following research ethics committee: Instituto Mexicano de Oftalmología (#22-CEI-003-2016215).

Data Availability Statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included in the manuscript.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior

Associate Editor: Ivan Maynart Tavares

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.