Adriane Macêdo Feitosa1,2,3; Maria Clara de Freitas Albano1; Sofia Pereira Lopes1; Josú Eduardo de Oliveira Miranda1; Thiago Carvalho Barros de Oliveira1,2,3; Pedro Javier Yugar Rodriguez2,3; Andrú Jucá Machado2; Mateus Macêdo Feitosa4; João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro1,2,3

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2025-0097

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: To evaluate the efficacy of different corticosteroid eye drop formulations (prednisolone acetate 1.0%, dexamethasone 1.0%, and loteprednol etabonate 0.5%) administered for different treatment durations (10 vs. 28 days) in controlling postoperative inflammation following uncomplicated cataract surgery.

METHODS: This randomized, masked clinical trial was conducted at the Instituto Cearense de Oftalmologia. Eligible participants were aged ≥50 yr and scheduled for routine cataract surgery. Exclusion criteria included preexisting ocular disease (elevated intraocular pressure, retinopathy, maculopathy, or uveitis) or concurrent medication use that could confound results. Patients were randomized to receive prednisolone acetate (1.0%), dexamethasone (1.0%), or loteprednol etabonate (0.5%) four times daily for 28 days (with tapering) or for 10 days. Medication bottles, prescriptions, and examiners were masked. Postoperative assessments included ocular symptoms, visual acuity, intraocular pressure, anterior chamber cell count and flare, pachymetry, endothelial cell density, and macular thickness over a 30-day follow-up.

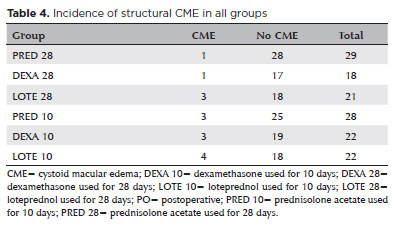

RESULTS: A total of 140 eyes from 140 patients were analyzed (29 prednisolone acetate 1.0%, 18 dexamethasone 1.0%, and 21 loteprednol etabonate 0.5% for 28 days; 28 prednisolone acetate 1.0%, 22 dexamethasone 1.0%, and 22 loteprednol etabonate 0.5% for 10 days). No significant differences were found among the six groups during follow-up. However, eyes treated with dexamethasone (1.0%) showed greater intraocular pressure fluctuations, particularly on Days 7 and 30, and a higher incidence of rebound inflammation in the 28-day regimen. Structural cystoid macular edema without visual impact was observed in 5.9% of eyes in the 28-day groups and 14.2% of eyes in the 10-day groups, as detected by optical coherence tomography at 30 days.

CONCLUSION: Equivalent postoperative inflammation control can be achieved using different corticosteroid eye drop formulations at varying treatment durations following cataract surgery. Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trials (ReBEC): RBR-2frpntv

Keywords: Adrenal cortex hormones; Cataract; Cystoid macular edema; Corticosteroids; Inflammation; Loteprednol etabonate; Ophthalmic solutions; Postoperative period; Intraocular pressure; Visual acuity

INTRODUCTION

An inflammatory reaction occurs in up to 95% of patients on the first day after cataract surgery(1,2). This is a frequent cause of discomfort, delayed recovery, and, in some cases, reduced visual acuity (VA). It may also lead to more serious complications, such as cystoid macular edema (CME), posterior synechiae, pain, photophobia, uveitis, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), and glaucoma(1). The main postoperative signs and symptoms include anterior chamber cellularity, corneal edema, and conjunctival hyperemia, with corneal edema being one of the principal factors limiting good VA in the immediate postoperative period(2).

Topical corticosteroids remain the preferred therapy for controlling inflammation and preventing CME because of their efficacy and safety, although no standardized protocol has been established(3-5). The topical route is favored for being noninvasive and for promoting better patient adherence(6). Despite their benefits, corticosteroid eye drops can cause side effects, such as elevated IOP, activation or prolongation of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, and potential systemic complications(6-8). The likelihood of adverse effects depends on the potency of the drug, its dosage, and its formulation(9).

Prednisolone acetate, a highly lipophilic and poorly water-soluble molecule, requires vigorous shaking before instillation to ensure dose uniformity(8). Because of this handling challenge, it is often prescribed at higher dosages, increasing the risk of adverse effects. Nevertheless, it has a well-established anti-inflammatory effect and has long been used after cataract surgery(10,11). Compared with dexamethasone, prednisolone acetate offers greater corneal permeability but lower potency(8).

Dexamethasone, in contrast, is highly hydrophilic and penetrates the cornea less effectively because of its mixed hydrophilic and lipophilic structure. To overcome this limitation, it is prepared as a micro-suspension(8).

Loteprednol etabonate, a derivative of prednisolone acetate, incorporates structural modifications that maintain good efficacy while allowing faster metabolism. This results in fewer adverse effects, particularly a markedly lower risk of IOP elevation, even with prolonged use (>28 days)(12,13).

Regarding dosage regimens, meta-analyses and systematic reviews suggest that the most common protocol is a 28-day course of corticosteroids, administered one drop every 6 h with weekly tapering(14). However, a multicenter clinical trial reported that a 7-day regimen controlled inflammation in approximately 85% of cases, although further studies are required to confirm these findings(4).

Currently, no standardized protocol exists for preventing or reducing inflammation after uncomplicated phacoemulsification(2). Given the limited evidence on cost-effectiveness, prescribing practices vary widely(3). This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of different corticosteroid formulations – prednisolone acetate, dexamethasone, and loteprednol etabonate – administered for different durations in controlling postoperative inflammation following uncomplicated cataract surgery.

METHODS

This randomized, double-masked clinical trial was conducted at the Instituto Cearense de Oftalmologia (ICO). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitário Christus (CAAE: 59298322.6.0000.5049) and registered with the Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trials (ReBEC: RBR-2frpntv). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants and inclusion criteria

Patients aged ≥50 yr scheduled for routine cataract surgery between October 2022 and January 2023 were eligible. Exclusion criteria included preexisting ocular conditions (elevated IOP, retinopathy, maculopathy, or uveitis), use of medications that could confound study outcomes, and intraoperative complications such as posterior capsular rupture.

Sample size calculation

Sample size estimation followed the methodology of Lane et al.(13). Assuming 90% power and a 95% confidence level for detecting the alternative hypothesis in a paired t test design, a sample size of eight to 18 patients per group was determined to be sufficient.

Randomization and treatment protocol

Participants were randomized using an electronic randomization tool to one of three treatments: prednisolone acetate 1% (PRED), Predfort (Allergan/AbbVie), Oftpred (Cristália), or Ster (Genom); dexamethasone 0.1% (DEXA), Maxidex (Alcon); loteprednol 5 mg/mL (LOTE), and Loteprol (Bausch + Lomb). They were further randomized to one of two regimens: four times daily for 28 days with weekly tapering, or four times daily for 10 days without tapering. All groups additionally received moxifloxacin eye drops, one drop four times daily for 7 days.

Blinding and masking

To maintain blinding, prescriptions were labeled only as "corticosteroid eye drops". Bottles were masked with stickers bearing the same generic label. Randomization, prescription preparation, and drug distribution were performed by a researcher independent of the evaluator. A single masked assessor (AMF) conducted all clinical evaluations.

Surgical procedure

All surgeries were performed by experienced surgeons using the same phacoemulsification platform (Centurion, Alcon).

Data collection

Data were collected at baseline and during four postoperative (PO) visits (Days 1, 7, 30, and 45).

• Preoperative assessment: Demographic data, comorbidities, allergies, and ophthalmic history were recorded. BCVA was measured using the logMAR scale, IOP with a Goldmann applanation tonometer, and anterior chamber cellularity/flare using the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) criteria. Pachymetry and endothelial cell density (ECD) were measured with specular microscopy (SP-1P, Topcon), and biometry with the IOLMaster 500 (Zeiss).

• Postoperative assessments (Days 1, 7, and 30): Outcome measures included ocular symptoms (numeric rating scale [NRS], 0–10), BCVA, IOP, anterior chamber cell/flare (SUN criteria), pachymetry, and ECD.

• Rebound effects (Days 30 and 45): Evaluations included anterior chamber reactions and symptom questionnaires. Patients were asked whether they self-administered drops or required assistance.

• Optical coherence tomography (OCT): Performed preoperatively and on Day 30 PO to assess macular thickness and detect CME. CME was defined as a ≥10% increase in central macular thickness with cystic changes; clinically significant CME was defined as CME plus <0.2 logMAR improvement in postoperative VA, following PREMED and ETDRS criteria(15).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York). Descriptive statistics included mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests, with Dunn's post hoc test as appropriate.

Variations in IOP across follow-up were assessed using nonparametric methods for repeated measures. Bonferroni corrections were applied to adjust for multiple comparisons. The influence of self-administration versus assisted administration was described qualitatively, recognizing adherence as a potential confounder.

Results are reported with exact p-values and confidence intervals to provide clarity on statistical significance and effect sizes.

RESULTS

A total of 140 eyes from 140 patients were included: 29 in the PRED Group, 18 in the DEXA Group, and 21 in the LOTE Group for 28 days; and 28 in the PRED Group, 22 in the DEXA Group, and 22 in the LOTE Group for 10 days. The mean age was 66.61 ± 8.68 yr, and 59.28% were female. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics. No statistically significant differences were observed among the groups in terms of cataract classification.

In the 28-Day LOTE Group, only 61.9% of patients had their drops administered by someone else, whereas in the other groups, this proportion was ≥82.7%. On the seventh PO Day, the LOTE Group showed significantly higher levels of anterior chamber flare and conjunctival hyperemia (p=0.003).

Ocular symptoms

Across 30 days, all patients demonstrated a statistically significant reduction or adequate control of mean scores for pain, foreign body sensation, and tearing (p<0.05; Table 2).

Drug tolerance

Most patients tolerated the eye drops well. Specifically, 84.2% in the PRED Group, 97.5% in the DEXA Group, and 88.3% in the LOTE Group reported no or only mild discomfort.

Visual acuity

Best-corrected VA (BCVA) improved significantly within 30 days after surgery in all groups (Figure 1). However, there were no significant intergroup differences (Day 7, p=0.369; Day 30, p=0.604).

Intraocular pressure

Figure 2 shows mean IOP values at days 1, 7, and 30 PO. The DEXA Groups consistently demonstrated higher mean IOP, with statistically significant differences across groups on Day 7 (p<0.05). Elevated IOP (>21 mmHg) occurred in one patient from the DEXA 10 Group on Day 7, and in two patients from the DEXA 10 Group, two from the DEXA 28 Group, and one from the PRED 10 Group on Day 30.

Inflammation control

All six groups achieved comparable inflammation control over 30 days. Flare and anterior chamber cellularity decreased significantly in all groups (Figure 3; Table 3). On Day 7, only 42.9% of patients in the LOTE 28 Group achieved flare=0, compared with 75.9% in the PRED 28 Group and 88.9% in the DEXA 28 Group. This did not impact VA or patient-reported symptoms. The group with the highest proportion of self-administered drops also exhibited higher flare levels on Day 7.

Pachymetry and ECD

All groups showed significant reductions in mean pachymetry and ECD between the preoperative and postoperative periods. However, no significant intergroup differences were observed at Day 7 or Day 30 (pachymetry [p=0.594 and p=0.414]; ECD [p=0.415 and p=0.353]; Figure 4).

Cystoid macular edema

The incidence of structural CME, detected by OCT regardless of VA, was 5.88% (n=5) in the 28-Day groups and 14.2% (n=10) in the 10-Day groups (Table 4). This difference was not statistically significant. Among the 15 cases, only one (LOTE 28 Group) was clinically significant (0.7%). This patient showed <0.2 logMAR improvement in VA, from 0.39 preoperatively to 0.30 on Day 30. One patient had diabetes, and two were prediabetic. Of the six hypermature cataracts, three (50%) developed CME (one each in the PRED 28, DEXA 28, and PRED 10 Groups).

Rebound effect

Fifteen patients (10.71%) experienced a rebound effect. Of these, 66.67% occurred in the 10-day groups, with 33.33% in the DEXA 10 Group. Only one case was observed in the PRED 28 Group. Symptoms included anterior chamber reaction, foreign body sensation, and conjunctival hyperemia, appearing a few days after discontinuing treatment. All patients were managed with reintroduction of corticosteroids at 6-h intervals, tapered by one drop every 5 days.

DISCUSSION

Corticosteroids are widely recognized as the gold standard for controlling inflammation and preventing CME after cataract surgery due to their potent anti-inflammatory effects and extensive evidence supporting their safety and efficacy(4,5,15). Awidi et al.(17) also highlighted topical steroids as the preferred choice for postoperative cataract care.

In this study, dexamethasone, although the most potent corticosteroid tested, did not demonstrate superior efficacy compared with the other treatments. Patients receiving dexamethasone showed a higher incidence of adverse effects, including elevated IOP and rebound inflammation. These findings are consistent with previous reports documenting similar complications with high-potency steroids(8).

Prednisolone acetate demonstrated a favorable safety profile, with minimal IOP fluctuations and few systemic side effects, while maintaining effective anti-inflammatory activity. Its superior ocular penetration is well documented(8), and it is frequently prescribed by American ophthalmologists(17). Our results support this preference, suggesting that prednisolone acetate may provide an optimal balance of efficacy and safety.

Loteprednol etabonate also effectively controlled inflammation but did not show a distinct safety advantage compared with the other corticosteroids. Although loteprednol is often promoted for its reduced side effects, this claim remains debated in the literature(13). Our results indicate that while effective, its safety benefits were not markedly superior to those of prednisolone acetate.

Both 10- and 28-day treatment regimens were well tolerated and provided adequate inflammation control. The efficacy of shorter regimens aligns with the LEADER7 clinical trial, which demonstrated substantial inflammation control within 7 days of topical dexamethasone use(4). Shorter regimens may improve comfort and reduce side effects, but further research is needed to assess their role in preventing CME.

Elevated IOP is a known risk of corticosteroid use. In this study, mean IOP decreased by 3.3 ± 2.4 mmHg compared with preoperative levels, consistent with the literature(18). However, dexamethasone was associated with the highest IOP levels and the most frequent cases of IOP >21 mmHg, particularly on the seventh PO day. This highlights the importance of careful monitoring and strategies to mitigate IOP-related side effects.

Rebound inflammation after abrupt corticosteroid withdrawal is well documented. Our findings showed rebound effects, especially when treatment was discontinued after 10 days, emphasizing the importance of tapering protocols. Further investigation into optimal discontinuation strategies is warranted to minimize rebound and improve patient comfort.

Administration methods may also influence treatment efficacy. Our results suggest that self-administration could compromise dosing accuracy, underscoring the need for strategies to improve adherence and delivery.

CME remains a major postoperative concern. Although our sample size was insufficient to provide definitive conclusions, CME was detected more often on OCT (5.88% in 28-day group vs. 14.2% in 10-day group) than by clinical assessment alone (0.7%). This agrees with Wielders et al.(19,20), who reported higher CME incidence when imaging was used routinely (15.6%–19.2%) compared with VA-based detection alone (1.4%–4%). These findings reinforce the importance of routine OCT screening, as many CME cases do not significantly impair vision(21). All patients with CME were treated with tapering corticosteroids plus topical NSAIDs for three months. Larger studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness and long-term outcomes of this combined therapy as well as to evaluate conservative management in clinically insignificant cases.

Of note, 50% of patients with hypermature cataracts developed CME, suggesting that advanced cataract may be an important risk factor(16). This highlights the potential role of adjunctive prophylactic therapies, such as NSAIDs, in prolonged surgeries requiring higher ultrasound energy.

Cost-effectiveness must also be considered. Although dexamethasone was the least expensive option, its higher incidence of side effects and rebound suggests that prednisolone acetate 1% for 28 days may be preferable, offering a better balance of safety and efficacy.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size, which may limit statistical power for CME analysis, and the absence of objective methods for anterior chamber inflammation, such as laser flare photometry. Furthermore, the study did not evaluate groups receiving NSAIDs alone or in combination, which should be addressed in future research.

In summary, all three corticosteroids effectively reduced postoperative inflammation after cataract surgery. Prednisolone acetate and loteprednol etabonate showed a more favorable safety profile compared with dexamethasone. Future studies should investigate adjunctive prophylactic therapies, optimal treatment duration, and tapering strategies to further enhance surgical outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the statisticians for their valuable contributions. Appreciation is also extended to the ICO and the Centro de Laser e Diagnose Ocular, along with their staff, for their support in this research.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Significant contribution to conception and design: Adriane Macêdo Feitosa, João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro. Data acquisition: Adriane Macêdo Feitosa, João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro, Maria Clara de Freitas Albano, Sofia Pereira Lopes, Josú Eduardo de Oliveira Miranda, Thiago Carvalho Barros de Oliveira, Pedro Javier Yugar Rodriguez, Andrú Jucá Machado. Data analysis and interpretation: Adriane Macêdo Feitosa, João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro, Thiago Carvalho Barros de Oliveira, Pedro Javier Yugar Rodriguez, Mateus Macêdo Feitosa. Manuscript drafting: Adriane Macêdo Feitosa, Mateus Macêdo Feitosa, João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Adriane Macêdo Feitosa, João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro, Maria Clara de Freitas Albano, Sofia Pereira Lopes, Josú Eduardo de Oliveira Miranda, Pedro Javier Yugar Rodriguez, Thiago Carvalho Barros de Oliveira. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Adriane Macêdo Feitosa, João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro, Maria Clara de Freitas Albano, Sofia Pereira Lopes, Josú Eduardo de Oliveira Miranda, Thiago Carvalho Barros de Oliveira, Pedro Javier Yugar Rodriguez, Andrú Jucá Machado, Mateus Macêdo Feitosa. Statistical analysis: Adriane Macêdo Feitosa, João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro. Obtaining funding: Not applicable. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Adriane Macêdo Feitosa, João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro, Andrú Jucá Machado. Research group leadership: Adriane Macêdo Feitosa, João Crispim Moraes Lima Ribeiro.

REFERENCES

1. Asbell PA, Dualan I, Mindel J, Brocks D, Ahmad M, Epstein S. Age-related cataract. Lancet. 2005 Feb 12;365(9459):599-609.

2. Miller KM, Oetting TA, Tweeten JP, Carter K, Lee BS, Lin S, et al. Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(1):P1-126.

3. Duong HV, Westfield KC, Singleton IC. Treatment Paradigm After Uncomplicated Cataract Surgery: A Prospective Evaluation. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2014;3(4):220-5.

4. Bandello F, Coassin M, Di Zazzo A, Rizzo S, Biagini I, Pozdeyeva N, et al. One week of levofloxacin plus dexamethasone eye drops for cataract surgery: an innovative and rational therapeutic strategy. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(11):2112-22.

5. Palacio-Pastrana C, Chávez-Mondragón E, Soto-Gómez A, Suárez-Velasco R, Montes-Salcedo M, Fernández de Ortega L, et al. Difluprednate 0.05% versus prednisolone acetate post-phacoemulsification for inflammation and pain: An efficacy and safety clinical trial. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:1581-9.

6. Fung AT, Tran T, Lim LL, Samarawickrama C, Arnold J, Gillies M, et al. Local delivery of corticosteroids in clinical ophthalmology: A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;48(3):366-401.

7. Assil KK, Greenwood MD, Gibson A, Vantipalli S, Metzinger JL, Goldstein MH. Dropless cataract surgery: modernizing perioperative medical therapy to improve outcomes and patient satisfaction. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021;32 Suppl 1:S1-12.

8. Gaballa SA, Kompella UB, Elgarhy O, Alqahtani AM, Pierscionek B, Alany RG, et al. Corticosteroids in ophthalmology: drug delivery innovations, pharmacology, clinical applications, and future perspectives. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2021;11(3):866-93.

9. Sherif Z, Pleyer U. Corticosteroids in ophthalmology: past - present - future. Ophthalmologica. 2002;216(5):305-15.

10. KhalafAllah MT, Basiony A, Salama A. Difluprednate versus prednisolone acetate after cataract surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e026752.

11. Caporossi A, Alessio G, Fasce F, Marchini G, Rapisarda A, Papa V. Short-term use of dexamethasone/netilmicin fixed combination in controlling ocular inflammation after uncomplicated cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:2847-54.

12. Dua HS, Attre R. Treatment of post-operative inflammation following cataract surgery - a review. Eur Ophthalmic Rev. 2012;6(2):98-103.

13. Lane SS, Holland EJ. Loteprednol etabonate 0.5% versus prednisolone acetate 1.0% for the treatment of inflammation after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39(2):168-73.

14. Juthani VV, Clearfield E, Chuck RS. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus corticosteroids for controlling inflammation after uncomplicated cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jul;7(7):CD010516.

15. Wielders LHP, et al. European multicenter trial of the prevention of cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery in nondiabetics: ESCRS PREMED study report 1. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(4):429-39.

16. Grzybowski A, Sikorski BL, Ascaso FJ, Huerva V. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema: update 2016. Clin Interv Aging. 2016; 11:1221-9.

17. Awidi AA, Stringer MD, Belcher H, Belcher S, Janus ED, St John AE. Prednisolone versus dexamethasone for prevention of pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Can J Ophthalmol. 2018; 53(2):131-4.

18. Perez CI, Chansangpetch S, Nguyen A, Feinstein M, Mora M, Badr M, et al. How to predict intraocular pressure reduction after cataract surgery? A prospective study. Curr Eye Res. 2019;44(6):623-31.

19. Wielders LH, Lambermont VA, Schouten JS, van den Biggelaar FJ, Worthy G, Simons RW, et al. Prevention of cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery in nondiabetic and diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015; 160(5):968-81.e3.

20. Baartman BJ, Gans R, Goshe J. Prednisolone versus dexamethasone for prevention of pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Can J Ophthalmol. 2018;53(2):131-4.

21. Yonekawa Y, Kim IK. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(1):26-32.

Submitted for publication:

April 16, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

August 26, 2025.

Approved by the following research ethics committee: Centro Universitário Christus - Unichristus (CAAE: 59298322.6.0000.5049).

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included in the manuscript.

Edited by

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior

Associate Editor: Andrú Messias

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.