INTRODUCTION

Many childhood neurodegenerative disorders affect vision, and therefore, diagnostic, prognostic, treatment, and rehabilitation pro grams involve visual evaluations. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCLs), which comprise the most common pediatric neurodegenerative disorders, are lysosomal storage diseases. Pathophysiologically, NCLs have been attributed to lysosomal lipofuscin ceroid deposits1 and are caused by enzymatic dysfunction2,3 consequent to autosomal recessive genetic mutations. To date, 14 genes have been linked to NCL.

Clinically, although NCL is the main cause of childhood pro gressi ve encephalopathy, it can manifest at varying ages, from early in childhood to during adulthood1,4,5. Worldwide, the re ported NCL incidence is one in 12,500 live newborn infants6. Curren tly, the three most frequently reported NCLs are infantile (INCL), Jansky-Biels chowsky disease (JB), and juvenile NCL (JNCL), also called Batten-Spielmeyer-Vogt-Sjogren disease.

NCLs present with various symptoms, including cognitive and motor decline, movement disorders, seizures, and retinopathy. In cases of INCL, the initial symptom onset occurs during the first 2 years of life, and the disease progresses quickly. INCL is characterized by severe developmental milestone losses, blindness, and microcephaly, and affected individuals have a life expectancy of 8-13 years1,2. JB disease first manifests as ataxia, progressive developmental milestone losses, epilepsy, and posterior vision losses in children of 2-4 years of age. JNCL, which is caused by a mutation in CLN3 (16p12), is the most common type of N CL. The onset of this form occurs during 4-8 years of age and is characterized by vision loss and progression to total blindness within 2 years, epilepsy, and motor and cognitive declines7-12.

NCL is an important ophthalmologic concern. Eye symptoms are usually the first sign of disease and can facilitate an early diagnosis. The disease course is mainly determined by central nervous system degradation and corresponding motor and intellectual deficits, and most patients die before reaching 30 years of age13. Retinal degeneration is an early lysosomal storage disease event, although the eye fundus appearance might remain normal or exhibit nonspecific abnormalities during the initial disease phase. However, a full-field electroretinogram (ERG) evaluation can detect changes that might precede fundus abnormalities, even during the initial NCL phase, as affected patients will not exhibit detectable ERG responses during progression14,15. The 2009 Hamburg-Germany NCL consensus therefore considered neuro-ophthalmologic evaluation as the first step toward a NCL diagnosis1. The present study therefore aimed to ascertain the characteristics of clinical and retinal dysfunction in patients with the NCL phenotype and to establish the role of ERG in early NCL diagnosis.

METHODS

Subjects

This retrospective study evaluated the case notes of 15 patients with the NCL phenotype who were referred to the Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision Laboratory, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Paulista School of Medicine, Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, for full-field ERG between July 2001 and December 2008. All patients, who were identified retrospectively, had undergone a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination before full-field ERG. Five patients each with INCL, JB disease, and JNCL were included. Neurologic and clinical abnormalities, consanguinity, and familial NCL history were determined from anamnesis and/or available medical records. The inclusion criterion was the presence of the NCL phenotype, which comprised visual complaints, neurodevelopmental involution, ataxia, and intractable epileptic seizures.

Ophthalmic examination

All patients underwent comprehensive ophthalmic exams, including slit-lamp, refraction, and dilated indirect ophthalmoscopy, performed by one of the authors (SSW), a retinal specialist. Presenting visual acuity (PVA) was measured in each eye using a retro-illuminated Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Chart of with Tumble "E" optotypes presented at a 4-m distance, when possible. Ocular motility was assessed using cover/uncover and alternate cover testing for distance and near vision testing, with and without glasses, with emphasis on the diagnosis of strabismus and nystagmus.

Full-field electroretinography

Each patient was administered a drop of tropicamide 1% with a drop of phenylephrine 10% to achieve a minimum pupil diameter of 6 mm and allowed to adapt to the dark for 30 min. Under dim red illumination, a bipolar contact lens electrode (Burian-Allen bipolar electrode; Hansen Ophthalmic Development Lab, Coralville, IA, USA) was placed on the corneal surface of one or both eyes, depending on the patient's cooperation. The corneal surface was anesthetized with two drops of tetracaine 1.0%, and a drop of methylcellulose 2% was placed on the inside surface of the contact lens electrode for protection and to ensure good electrical contact. A gold cup ground electrode was applied to the earlobe. All stimuli were presented in a Ganzfeld dome (LKC Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Signals were amplified (gain, 910,000; 0.3-500 Hz), digitized, averaged, saved, and displayed using a digital plotter (UTAS E-3000 System, LKC Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). ERGs were recorded according to the standard International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) protocol16. The stimulus and recording details have been described previously17. The peak-to-peak amplitude (µV) and implicit time (ms) from each step of the ISCEV standard protocol were determined, and amplitudes ≤2 µV were considered non-detectable responses. Retinal dysfunction was classified as cone only, rod only, rod-cone, or cone-rod dysfunction according to standard clinical criteria, with consideration of history, fundus examination findings, and previous full-field ERG responses (recorded from one or both eyes with bipolar contact lens electrodes). ERG peak-to-peak amplitude and implicit time data from each step according to the ISCEV standard protocol were measured and compared with normative data from our own laboratory18.

RESULTS

The 15 enrolled patients (three males) belonged to 13 families and ranged in age from 1 to 12 years (mean=5.9; median=5). The 12 females ranged in age from 3 to 12 years (mean=6.6; median=6), whereas the males ranged in age from 1 to 4 years (mean=3; median=4). Symptom onset ranged from 0.2 to 7 years (mean=3.3; median=3) among females and from 1 to 3 years (mean=2.3; median=3) among males. Seven (46.7%) patients had a history of consanguinity, and five (33.3%) reported a similar familial case. The self-reported skin color was white for 13 (86.7%) patients, and black for two (13.3%) patients.

Visual symptoms

The PVA results of the 15 patients are shown in table 1. Visual acuity in the better-seeing eye could be measured in only two patients, who received scores of 20/25 and 20/250. Of the remaining 13 patients, seven (46.7%) could not fixate on nor follow lights and objects, and six (40.0%) could fixate on and follow light and objects. The most frequent visual symptom was progressive visual acuity loss, reported by 10 (66.7%) patients. One patient reported only visual loss as the initial complaint, whereas this symptom was associated with other neurologic features in the other nine patients (60%). Five (33.3%) patients reported no visual symptoms.

Clinical assessment

Epilepsy was the initial presenting neurological symptom in 14 (93.3%) patients. Thirteen (86.6%) patients presented with neurodevelopmental involution, five exhibited ataxia, and one developed cardiopathy. Most patients (n=13) had multiple neurologic symptoms. The patients were then classified into three groups based on their clinical characteristics and age at initial symptom onset. All five JB disease patients presented with epilepsy and neuro psycho-motor involution (NPMI). Among the five patients with INCL, all had epilepsy and four presented with NPMI. All five JNCL patients presented with epilepsy; four presented with NPMI and reduced visual acuity, whereas one patient did not report these symptoms. The major clinical characteristics are shown in table 1.

Table 1 Clinical findings of 15 patients with the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis phenotype

| ID | Type | Gender | Age ERG testing (y) | Initial symptoms age (y) | Presenting symptoms | Consan guinity | Family history | PVA RE | PVA LE | Ophthalmic changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | JB | F | 04 | 3.00 | E; NPMI | N | Y | 20/25 | 20/30 | None |

| 02 | JB | M | 04 | 3.00 | E; ATX; NPMI; LVA | Y | Y | DF | DF | PEA; ODP |

| 03 | JB | M | 04 | 3.00 | ATX; E; NPMI | N | N | F | F | Bilateral ODP |

| 04 | JB | F | 06 | 3.00 | E; LVA; NPMI | N | N | DF | DF | ODP; bilateral SAN; PMP |

| 05 | JB | F | 05 | 5.00 | E; NPMI; Cardiopathy | Y | N | F | F | None |

| 06 | INCL | F | 05 | 0.25 | E; NPMI; ATX; LVA | Y | N | F | F | Nystagmus |

| 07 | INCL | F | 08 | 2.00 | E; NPMI; LVA | Y | Y | DF | DF | None |

| 08 | INCL | F | 04 | 2.00 | E; ATX;NPMI | N | N | F | F | None |

| 09 | INCL | M | 01 | 1.00 | E; LVA | N | N | F | F | None |

| 10 | INCL | F | 03 | 2.00 | E;NPMI; LVA; ATX | N | N | DF | DF | None |

| 11 | JNCL | F | 08 | 6.00 | E; NPMI; LVA | N | N | DF | DF | PMP; NRA; PEA; ODP |

| 12 | JNCL | F | 06 | 4.00 | E; NPMI | Y | N | F | F | PMP |

| 13 | JNCL | F | 12 | 6.00 | E; LVA | N | N | 20/250 | 20/400 | ODP; BEM |

| 14 | JNCL | F | 10 | 4.00 | E; NPMI; LVA | Y | Y | DF | DF | XT; ODP; BEM |

| 15 | JNCL | F | 08 | 7.00 | E; NPMI; LVA | Y | Y | DF | DF | XT; ODP; BEM |

PVA= presenting visual acuity; E= epilepsy; LVA= progressive loss of visual acuity; ATX= ataxia; NPMI= neuro-psycho-motor involution; ONA= optic nerve atrophy; XT= exotropia; JB= Jansky-Bielschowsky; JNCL= juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis; INCL= infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis; BEM= bull's eye maculopathy; PEA= pigmentary epithelium atrophy; ODP: optic disk pallor; PMP= peri-macular pigmentary deposit; NRA= neuro-sensorial retinal atrophy; DF= does not fixate, does not follow objects/light; F= fixates and follows objects and light; SAN= severe arteriolar narrowing; RE= right eye; LE= left eye.

Ophthalmic assessment

The fundus examination yielded normal results in seven (46.7%) patients, including two with JB disease and all with INCL disease. In contrast, all patients with JNCL exhibited fundus changes. The observed fundus changes included optic disk pallor in seven (46.7%) patients, bull's eye maculopathy in three (20%, all JNCL patients), peri-macular pigmentary deposits in three (20%), retinal pigmentary epithelium atrophy in two (13.3%), severe arteriolar narrowing in one, and neurosensory retinal atrophy in one patient. Six (40%) patients presented with two or more retinal abnormalities. Furthermore, two (13.3%) patients exhibited exotropia, and one patient had nystagmus (Table 1).

Full-field ERG and its correlations

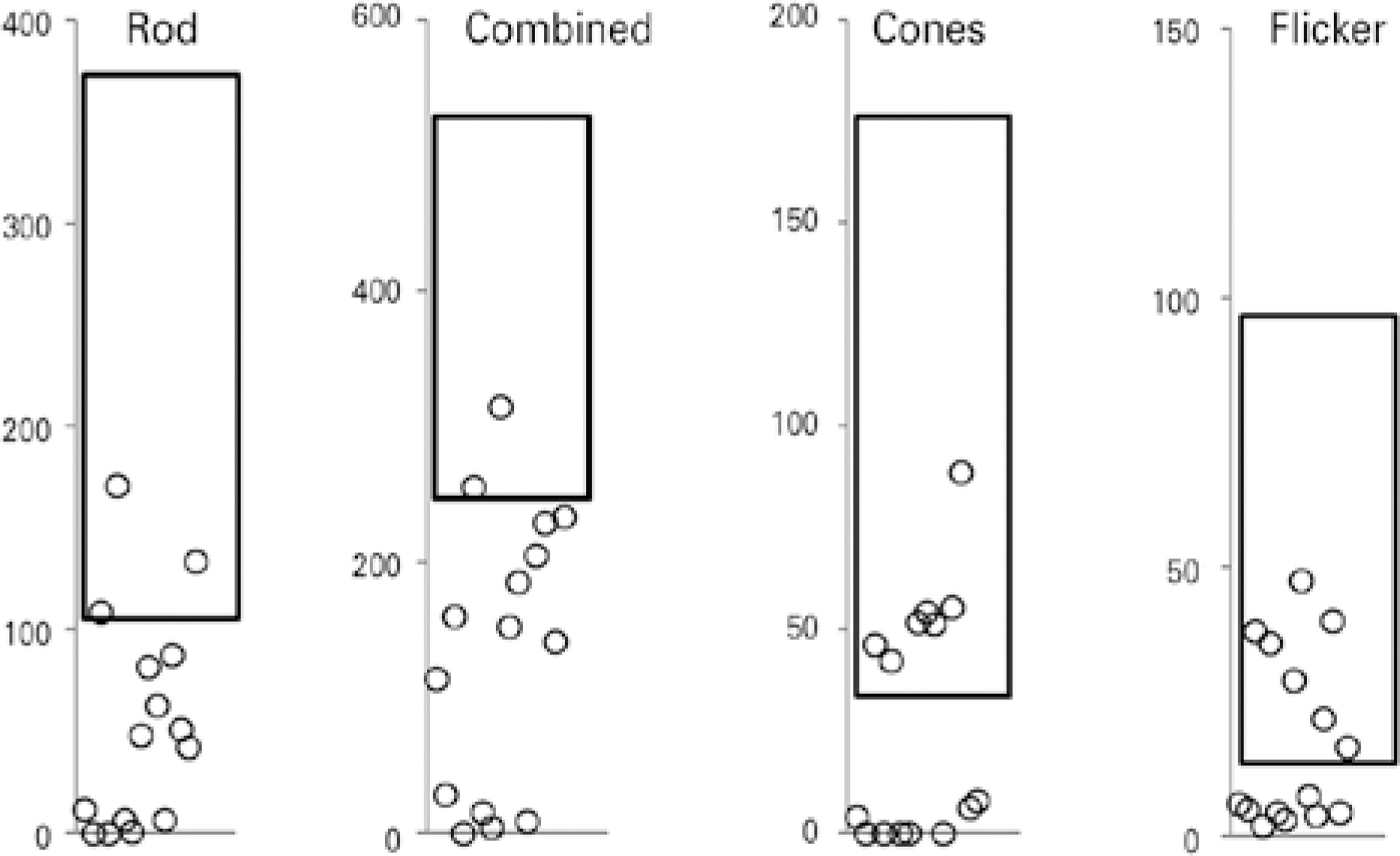

ERG abnormalities were found in all 15 patients. Figure 1 summarizes the ERG parameters for scotopic (rod and mixed) and photopic (cone and flicker) retinal function obtained from NCL patients, compared with normative data from our own laboratory. Scotopic (rod and mixed) and photopic (cone and flicker) a and b wave amplitudes and implicit times are shown in table 2, where abnormal values are indicated in bold. Cone-rod dysfunction was observed in six patients (cases 1, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10), rod-cone dysfunction in one patient (case 2), and both types in eight patients (cases 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15) (Table 2).

Figure 1 Electroretinogram (ERG) amplitudes (μV) for rod, combined, cone, and 30-Hz flicker responses recorded from one eye in each of 15 patients with the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis phenotype, compared with normative data from our own laboratory (rectangle=mean ± two standard deviations).

Table 2 Amplitudes (mV) and implicit times (ms) from full-field electroretinogram (ERG) recordings of 15 patients with the NCL phenotype

| ID | Type | Tested eye | Rod a-wave | Rod b-wave | Rod b-wave IT | Combined a-wave | Combined b-wave | Combined b-wave IT | Cone a-wave | Cone b-wave | Cone b-wave IT | 30 Hz Flicker Amplitude | 30 Hz Flicker IT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | JB | LE | 0-7.7 | 019.2 | 122.0 | 0-23.4 | 090.4 | 81.0 | 0-1.3 | 02.7 | 64.0 | 06.2 | 40.5 |

| 02 | JB | LE | 0-0.0 | 000.0 | nd | 0-11.6 | 017.8 | 72.0 | 0 | 00.0 | nd | 05.2 | 38.9 |

| 03 | JB | LE | 0-6.0 | 109.1 | 101.5 | 0-71.4 | 159.9 | 47.0 | -20.3 | 46.9 | 27.5 | 38.3 | 27.8 |

| 04 | JB | LE | -00.0 | 000.0 | nd | -000.0 | 000.0 | nd | 0 | 00.0 | nd | 02.1 | 36.7 |

| 05 | JB | LE | 0-2.7 | 071.3 | 099.5 | 0-46.2 | 256.0 | 53.5 | 0-2.0 | 42.5 | 35.0 | 35.9 | 33.7 |

| 06 | INCL | LE | 0-5.8 | 006.8 | 097.5 | 0 0-0.4 | 015.4 | 28.0 | 0 | nd | nd | 04.6 | 32.9 |

| 07 | INCL | LE | 0-1.1 | 000.0 | nd | 00-4.9 | 000.0 | nd | 0 | 00.0 | nd | 03.1 | 30.0 |

| 08 | INCL | LE | 0-10.2 | 058.3 | 113.0 | 0-48.3 | 102.8 | 54.5 | -14.4 | 37.6 | 36.5 | 29.1 | 34.2 |

| 09 | INCL | RE | 0-2.9 | 085.0 | 103.5 | 0-42.1 | 110.2 | 45.5 | -13.0 | 41.5 | 35.0 | 24.5 | 31.5 |

| 10 | INCL | LE | -05.0 | 041.3 | 107.5 | 0-10.0 | 185.7 | 63.0 | 0-6.6 | 30.3 | 34.0 | 07.6 | 33.4 |

| 11 | JNCL | LE | -00.0 | 006.4 | 121.0 | -000.0 | 009.1 | 49.5 | 0 | 00.0 | nd | 04.0 | 28.0 |

| 12 | JNCL | RE | -0 3.5 | 091.7 | 099.0 | 0-96.3 | 109.4 | 43.0 | 0-6.6 | 49.1 | 39.5 | 22.0 | 39.3 |

| 13 | JNCL | RE | -11.2 | 040.0 | 072.0 | 0-80.1 | 159.4 | 38.5 | -43.0 | 45.9 | 31.0 | 40.2 | 34.5 |

| 14 | JNCL | LE | -18.0 | 042.2 | 119.5 | 0-52.4 | 111.2 | 66.0 | 0-0.4 | 06.0 | 65.0 | 04.5 | 38.6 |

| 15 | JNCL | RE | 0-7.3 | 133.7 | 103.5 | -119.1 | 234.0 | 75.0 | 0-0.4 | 08.1 | 39.5 | 14.6 | 38.2 |

NCL= neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis; JB= Jansky-Bielschowsky; INCL= infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis; JNCL= juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis; IT= implicit time (ms); nd= non-detectable; bold values are abnormal and indicate reduced amplitude or increased IT.

Patients with JB disease

Two JB disease patients with normal fundoscopy findings and mild visual impairment presented with cone-rod dysfunction (cases 1, 5). Two other patients (cases 2, 4) with the worst visual acuity (did not fixate/follow objects/light) exhibited more fundoscopic abnormalities compared to those with better acuity, severe retinal changes, undetectable rod responses, and very low-amplitude cone responses, characteristic of diffuse retinal dysfunction affecting both systems (rods and cones). One patient (case 3) presented with optic disk pallor and cone-rod ERG dysfunction. Generally, those with the lowest visual acuity had more severe ophthalmic changes.

Patients with INCL

All five patients had normal fundus examinations (case 6 had nystagmus) and abnormal ERG findings. Three patients exhibited cone-rod dysfunction (cases 6, 9, 10), and two presented with diffuse retinal dysfunction affecting both systems (cases 7, 8). There was no correlation between visual acuity and ERG dysfunction.

Patients with JNCL

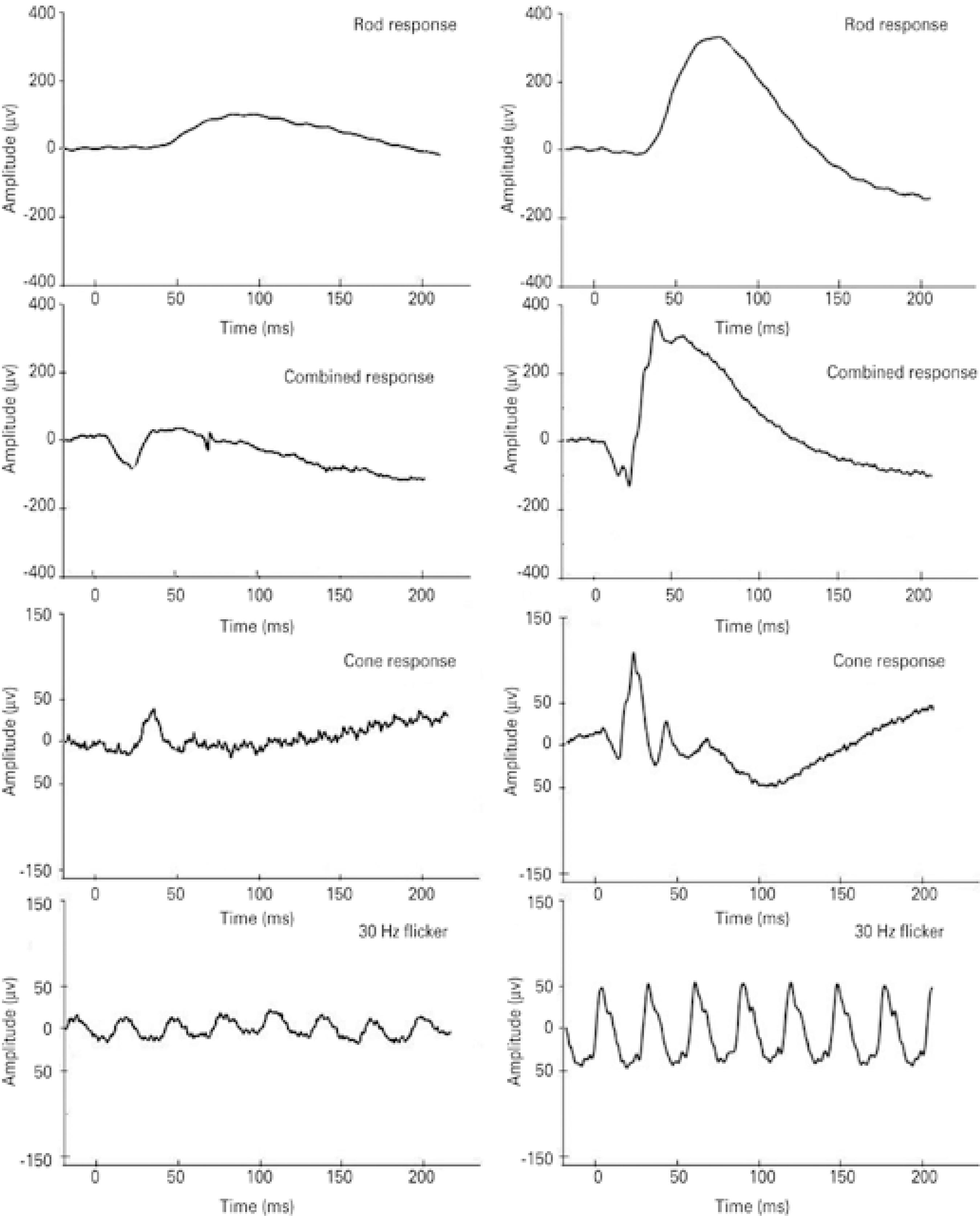

All five patients exhibited fundus changes, with ERG results indi cative of diffuse retinal dysfunction affecting both systems (rods and cones). Figure 2 presents representative standard full-field ERG waveforms (rod, maximal, cone, and 30 HZ-flicker responses) from a patient with the NCL phenotype (left) and a healthy subject (sex- and age-matched).

Figure 2 Representative standard full-field electroretinogram (ERG) waveforms (rod, combined, cone, and 30 Hz-flicker responses). Amplitudes (μV) and time (ms) are presented on the Y and X axes, respectively. Data are shown from case #12, a 6-year old female patient (left panels) with the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis phenotype, and a 6-year old female healthy subject (right panels).

DISCUSSION

This retrospective case series of the three most common forms of the NCL phenotype demonstrated that all 15 included patients exhibited phenotypic NCL characteristics, including progressive visual impairment, epilepsy, neurodevelopmental milestone losses, and ataxia. In addition, almost half of the patients reported a family history of consanguinity, as would be expected with recessive genetic transmission.

In our series, the most frequent presenting visual symptom was progressive visual acuity loss, a hallmark of NCL, in 10 (66.7%) patients4-6. The five (33.3%) patients with no visual symptoms at the initial disease phase (three, one, and one with JB disease, INCL, and JNCL, respectively), were the youngest among our subjects, and will likely develop these symptoms during disease progression19. Among the five patients with JNCL (all female), four initially presented with progressive visual acuity loss at a mean age of 5.7 years, thus corroborating previous studies10.

Seven (46%) patients had a normal fundus, including two and five classified as having JB disease and INCL, respectively. Those findings corroborated previous reports of normal fundus findings during the initial NCL phase15-19. On the other hand, all JNCL patients (i.e., older patients) presented with detectable fundoscopic abnormalities affecting the central retina, med-peripheral retina, retinal vasculature, and optic disk. Three of 5 JNCL patients, or 60%, presented with bull's eye maculopathy, a higher frequency than the 22% reported by Collins et al.20.

Regarding ERG, full-field abnormalities were observed in all 15 patients to varying degrees, even those with no visual complaints and/or normal fundus findings. These findings agree with previous reports in which abnormal ERG findings were observed during the early stages of all three NCLs, with progression to a non-recordable status15,20. As per previous reports, the earliest ERG manifestations of INCL and JNCL include a marked loss and increased implicit latency of the scotopic and photopic b-wave, with relative preservation of the a-wave. This defect, which is evident for both rods and cones, suggests preservation of the photoreceptor outer segment function, with severely disturbed transmission of signals to bipolar cells. These ERG findings support the early existence of a relative pre- or post-synaptic block of effective neurotransmission from the photoreceptor inner segments to second-order bipolar neurons in affected patients14,15.

Patients with JB disease exhibited decreases in cone function of 25% to 95%, whereas rod function ranged from normal to non-de tectable. Among patients with INCL, the ERG cone and rod functions ranged from normal to a decrease of 95%. Those with JNCL exhibited decreases in cone and rod function from 8% to 95% and from 15% to 95%, respectively. Under conditions of dark adaptation, only three and two patients respectively exhibited rod and combined responses with normal amplitudes. During the light adaptation phase, seven patients each exhibited cone and flicker responses with normal amplitudes (Figure 1). Our finding suggests a more pronounced impairment of rod function and relative preservation of cone function among this series of patients with NCL. Previous histopathologic evaluations of retinas affected by NCL revealed reduced cell numbers and auto-fluorescent lipofuscin granules in all retinal layers, with a central epi-retinal membrane. The periphery was better preserved but featured short photoreceptor outer segments. Further immunofluorescence analysis revealed degenerate rods and cones throughout the retina, with better preservation in peripheral areas15.

Despite research into experimental therapies, NCL is currently untreatable, and early diagnosis is needed to implement appropriate counseling and support21. Our above results confirm the early deleterious effects of NCL on retinal function and visual acuity, and indicate that full-field ERG may be useful for NCL diagnosis, particularly in patients who do not have access to genotyping.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin