INTRODUCTION

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a malignant hematopoietic neoplasia, which is rare in adults(1,2). In this condition, lymphoid precursors proliferate and replace normal marrow elements. Lymphoblasts also proliferate in other organs, most commonly in the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes(1). Patients with ALL frequently present with fever and other symptoms related to either the lack of normal marrow cells (anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia) or symptoms related to the direct infiltration of the marrow or other organs by leukemic cells(1). In contrast to pediatric ALL, and despite intensive treatment, only 20%-46% of adults with ALL are cured(1,3).

Almost any ocular structure can be affected by leukemia, either through direct infiltration, hemorrhage, or ischemia (due to anemia, thrombocytopenia, or leukostasis) or as a consequence of opportunistic infections(4). The fundus of patients with ALL often exhibit intraretinal and/or white-centered hemorrhage, tortuous dilated veins, cotton wool spots, vascular sheathing, and leukemic infiltrates(4,5); meanwhile, serous retinal detachment is a rare complication(4,5). Although fundus alterations are present in up to 90% of ALL patients over the course of the disease(5) and up to 50% at the time of diagnosis(6), these are usually asymptomatic and are rarely presenting sign of the disease(5).

The purpose of our study was to describe a case of ALL presenting with bilateral serous macular detachment in an adult.

CASE REPORT

We describe the case of a 63-year-old female who was admitted to the emergency unit with bilateral, painless, and progressive loss of visual acuity developing over two weeks. The complete clinical history was recorded, and physical examination revealed fever (38.3°C) and cervical lymphadenopathy.

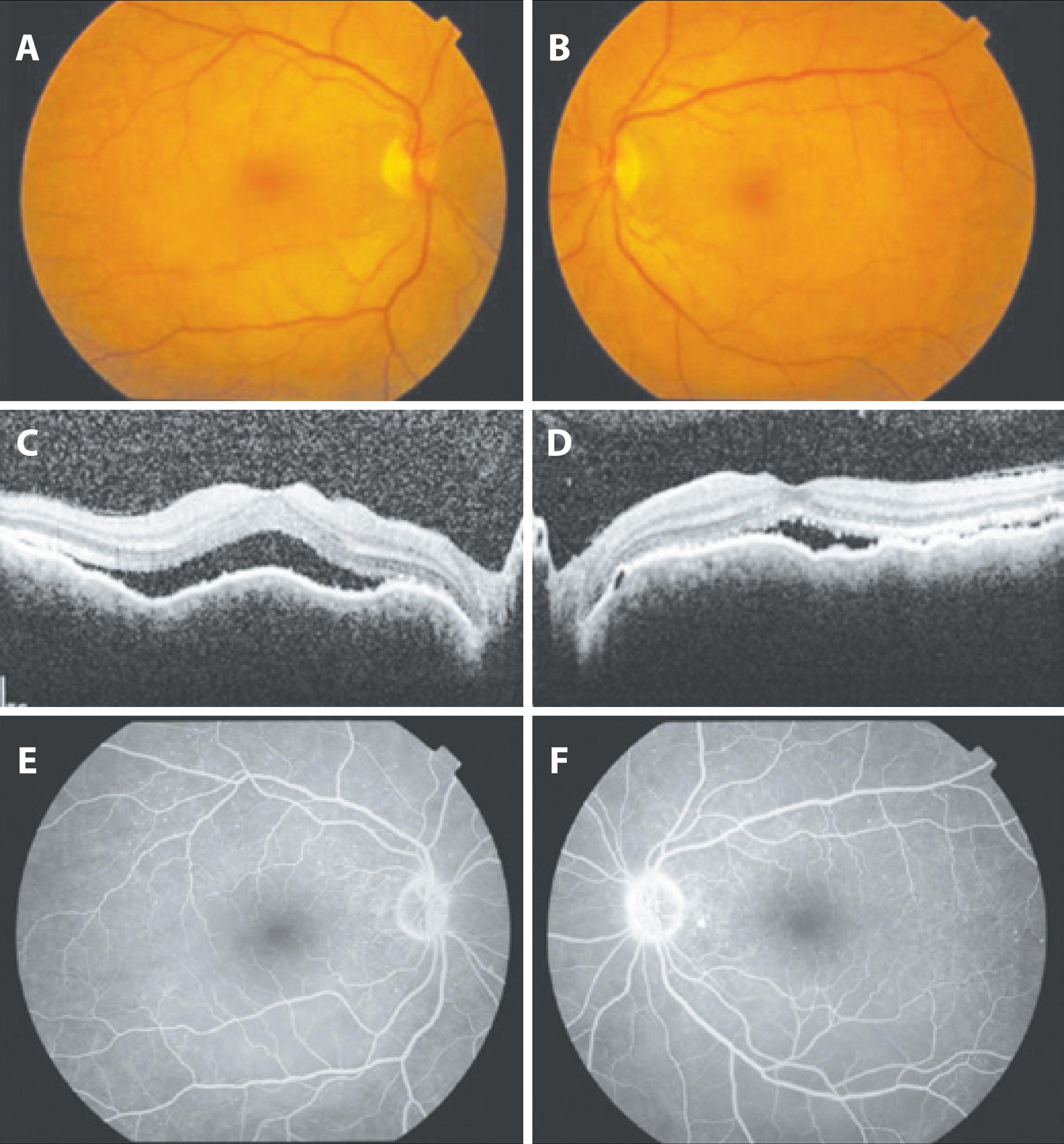

Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 2/10 in the right eye and 3/10 in the left eye. Fundus examination (Figure 1 A, B) showed bilateral macular serous detachment, which was confirmed by optical coherence tomography (Figure 1 C, D). Central macular thickness on the right and left eye was 638 μm and 423 μm, respectively. Fluorescein angiography (Figure 1 E, F) revealed hyperfluorescent pinpoints in the posterior poles. The limits of the macular detachment were revealed in the late phase of the angiogram.

Figure 1 Findings at presentation: A) and B) Fundus photographs of the right and left eye, respectively, showing shallow serous macular detachment. C) and D) Optical coherence tomography (horizontal sections) of the right and left eye, respectively, at the level of the fovea, showing neurosensory detachment, with central macular thickness of 638 μm and 423 μm in the right and left eye, respectively. E) and F) Fluorescein angiogram of the right and left eye, respectively, showing hyperfluorescent pinpoints in the posterior poles. The limits of the macular detachment were revealed in the late phase of the angiogram.

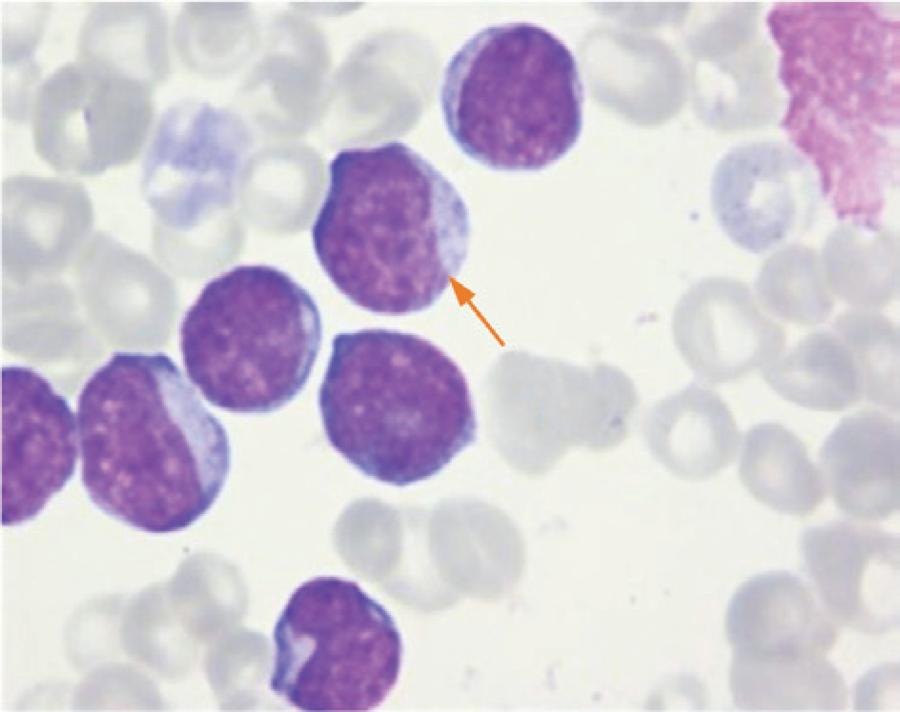

Blood tests (Table 1) were performed and revealed anemia, neutropenia with 80% blast cells in the white cell series, thrombocytopenia, and marginally increased C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Based on these findings, the patient was referred to the Hematology Department, where bone marrow examination was performed (Figure 2), revealing increased cellularity with 97% blast cells. The patient was diagnosed with ALL type B (CD10+) using immunophenotyping.

Table 1 Blood tests performed upon admission

| Erythrocytes↓ | 2.42 x 1012/L |

| Hemoglobin↓ | 8.2 x 10g/L |

| Hematocrit↓ | 24.7% |

| Mean cell volume↑ | 102.1 fL |

| Mean cell hemoglobin↑ | 33.9 pg |

| Red cell distribution width↑ | 17.5% |

| Leucocytes↑↑ | 25.40 x 109/L |

| Neutrophils↓ | 0.76 x 109/L |

| Eosinophils | 0.00 x 109/L |

| Basophils | 0.00 x 109/L |

| Lymphocytes | 4.32 x 109/L |

| Monocytes↓ | 0.00 x 109/L |

| Blasts↑↑ | 80% |

| Platelets↓ | 66 x 109/L |

| Platelet distribution width↑ | 18.8% |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 12 mm/h |

| C-reactive protein↑ | 14.4 mg/L |

| Liver and kidney function tests, autoimmune test, infection serological tests | No alterations |

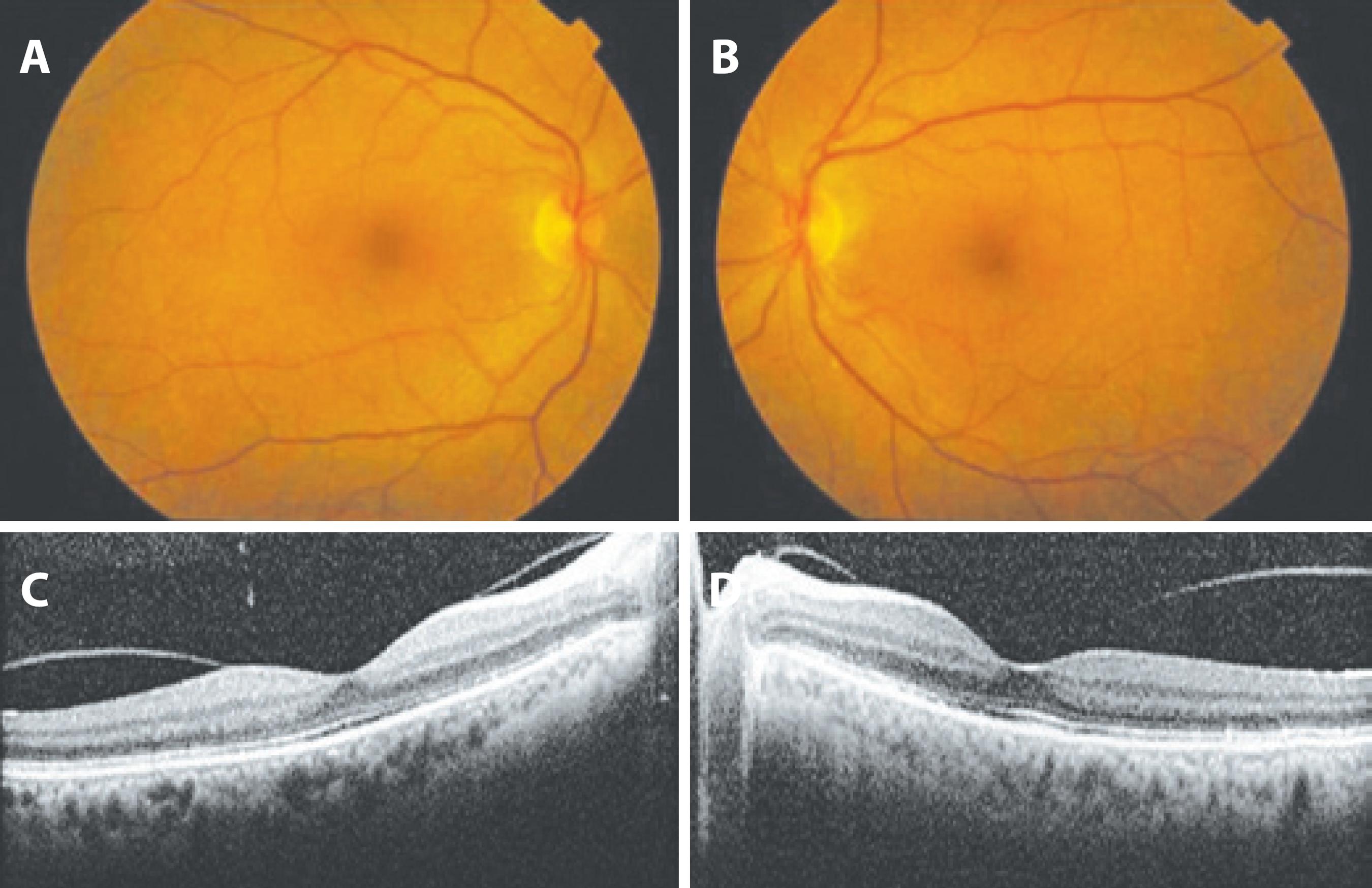

Intensive systemic chemotherapy (rituximab-hyperCVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) regimen plus intrathecal therapy (methotrexate/cytarabine) was scheduled and initiated immediately. After the first chemotherapy cycle, complete remission was achieved, and a BCVA of 10/10 was obtained in both eyes with reattachment of the macula (Figure 3) after the second cycle. One year after the diagnosis, the patient remains in complete remission without any ophthalmologic alterations.

Figure 3 Findings after the second cycle of chemotherapy: A) and B) Fundus photographs of the right and left eye, respectively, with no significant alterations. C) and D) Optical coherence tomography (horizontal sections) of the right and left eye, respectively, at the level of the fovea, showing reattached maculas.

DISCUSSION

Ophthalmological involvement in leukemia, which is more common in acute than in chronic disease(4,6), is not unusual but is rarely a presenting sign of the disease(5). Although leukemic retinopathy (intraretinal hemorrhages, white-centered hemorrhages and cotton-wool spots) is the most frequent fundus finding and retinal infiltrates are easily seen, choroidal infiltration is rarely observed clinically (5). However, the choroid is affected in 30% to 93% of the cases as demonstrated by histopathological studies(2,4,7), and decreased thickness after chemotherapy has been reported by Bajenova et al.(7).

When the choroidal infiltration is severe, it leads to serous retinal detachment, which is reported to be shallow in the posterior pole, more common in adults, and bilateral(5).

Other diseases may present with serous macular detachment, such as central serous chorioretinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, Harada´s syndrome, melanoma, hemangioma, metastases, sympathetic ophthalmitis, posterior scleritis, and uveal effusion syndrome. In our case, the existence of fever and cervical lymphadenopathy, and the absence of other relevant ophthalmologic or systemic findings, as revealed by clinical history and physical examination, led to the suspicion of hematologic neoplasia, with the angiogram results correlating with the findings described in the scientific literature(5). Moreover, the resolution of the macular detachment with systemic chemotherapy was in favor of our theory that serous macular detachment was due to leukemic choroidal infiltration.

The physiopathological mechanism postulated(5) is that choroidal infiltration leads to a decreased blood flow in the choriocapillaris, resulting in ischemia and the disruption of the intercellular tight junctions or the necrosis of the retinal pigment epithelium, as evidenced by the multifocal hyperfluorescent pinpoints in the early phases of fluores cein angiography. This decompensated posterior blood-retinal barrier leads to exudation as evidenced by the diffuse subretinal accumulation of fluorescein in the late phase of the angiogram.

This rare case illustrates the importance of a systematic examination in managing a case of bilateral macular serous detachment, with no other signs suggestive of local injury. This is particularly important when early treatment is imperative and is critical to patient survival.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin