INTRODUCTION

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) is a retinal vascular pathology that is considered as a vitreoretinal dystrophy. It emerges in the first decade of life and may lead to vision threatening complications at any subsequent time(1). FEVR was first described by Chriswick and Schepens in 6 patients in 1969(2). These patients displayed a pathology resembling retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), but had no history of prematurity or oxygen support at birth. FEVR cases are often overlooked due to its low prevalence, highly asymptomatic clinical course, and diversity of symptoms. Characteristically, it is bilateral but clinical findings may be asymmetric(3). Clinical findings may include macular ectopia, retinal folds, vascular tortuosity, retinal neovascularization, telangiectasia, peripheral retinal ischemia, vitreoretinal interface disorders, vitreus hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, and subretinal exudation. These findings may be seen in variable combinations and may resemble premature retinopathy(4). The severity of the disease varies from minimal peripheral avascular segments to retinal folds extending from the posterior pole(5). The hallmark finding of FEVR is the presence of peripheral avascular retinal zones(3).

CASE

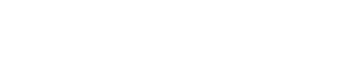

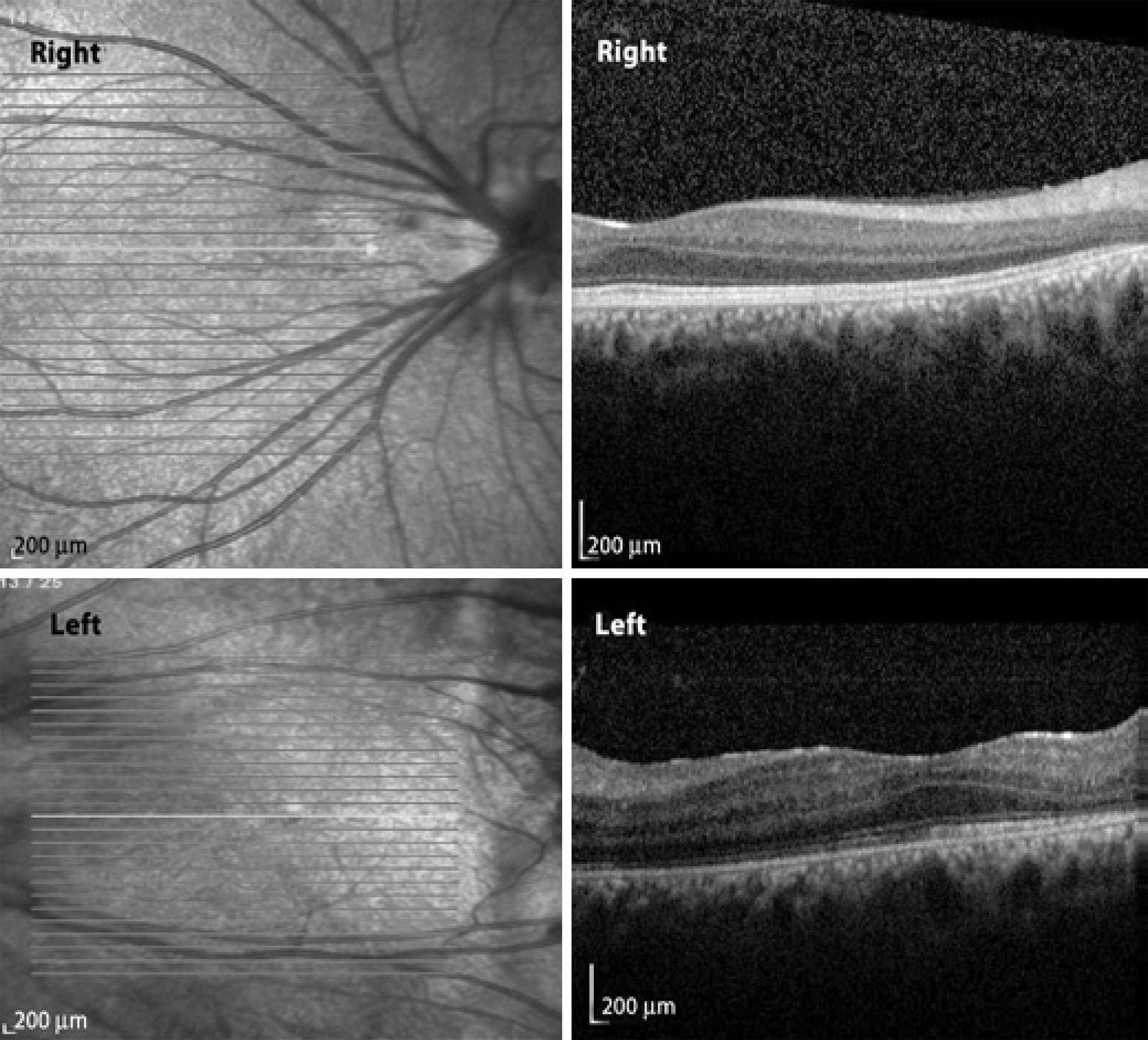

A 21 year-old Caucasian man presented with a complaint of nyctalopia. This symptom was already present in early childhood and had progressed with time. The patient informed us that his father and brother had also suffered from the same symptoms. The best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes and slit lamp biomicroscopy results were unremarkable. Fundoscopic examination revealed peripheral avascular zones, exudation from the retinal vasculature, retinal telangiectasia, anastomosis in both eyes, and retinal dragging at the temporal retinal region in both eyes. Peripheral retinal avascular zones, telangiectasia, and anastomosis were confirmed by fluorescein angiography. The midperipheral retina of the left eye also presented coalescing retinal pigment in epithelial atrophic areas (Figure 1). Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) analysis determined that the macular region was normal in both eyes.

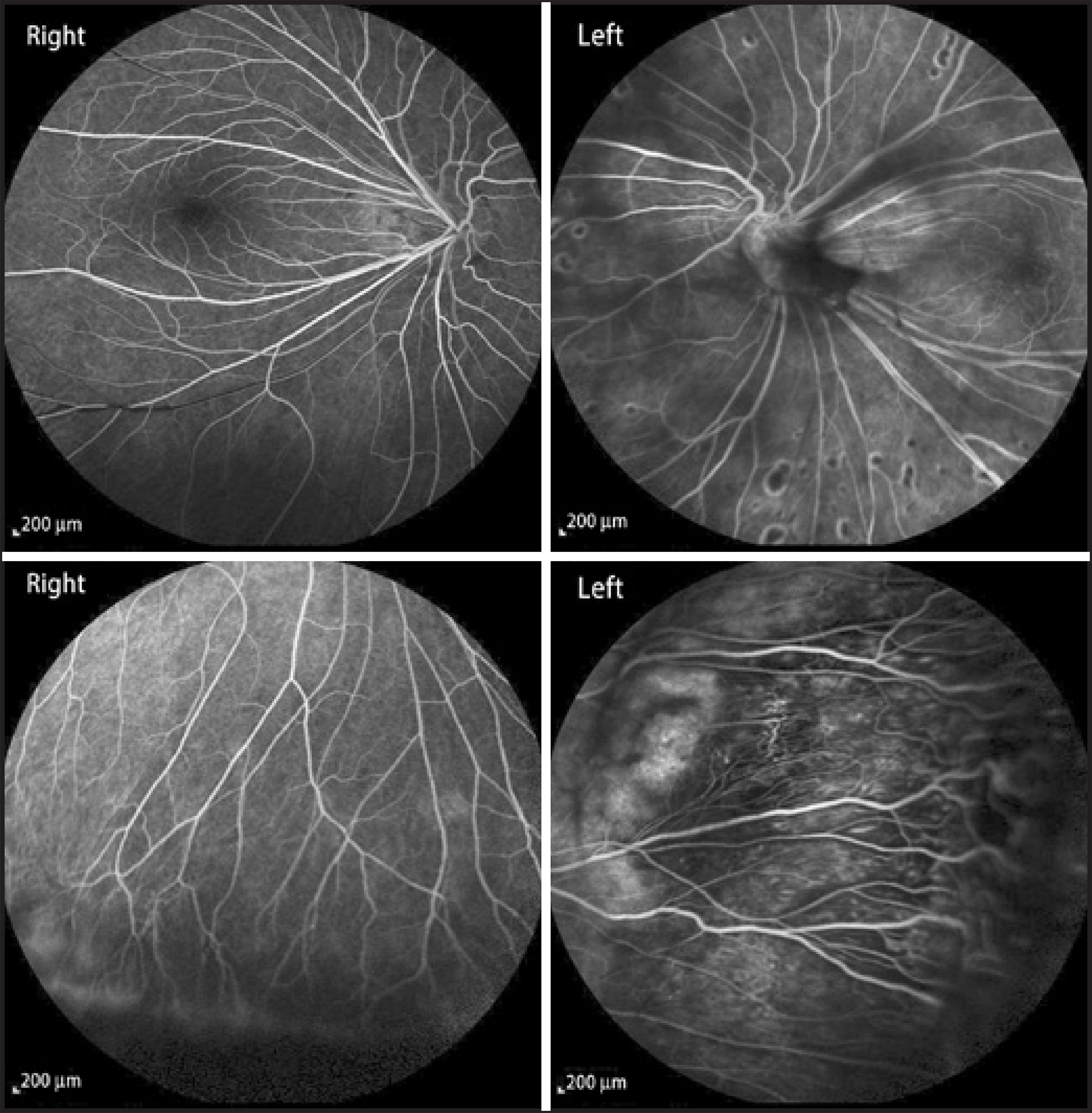

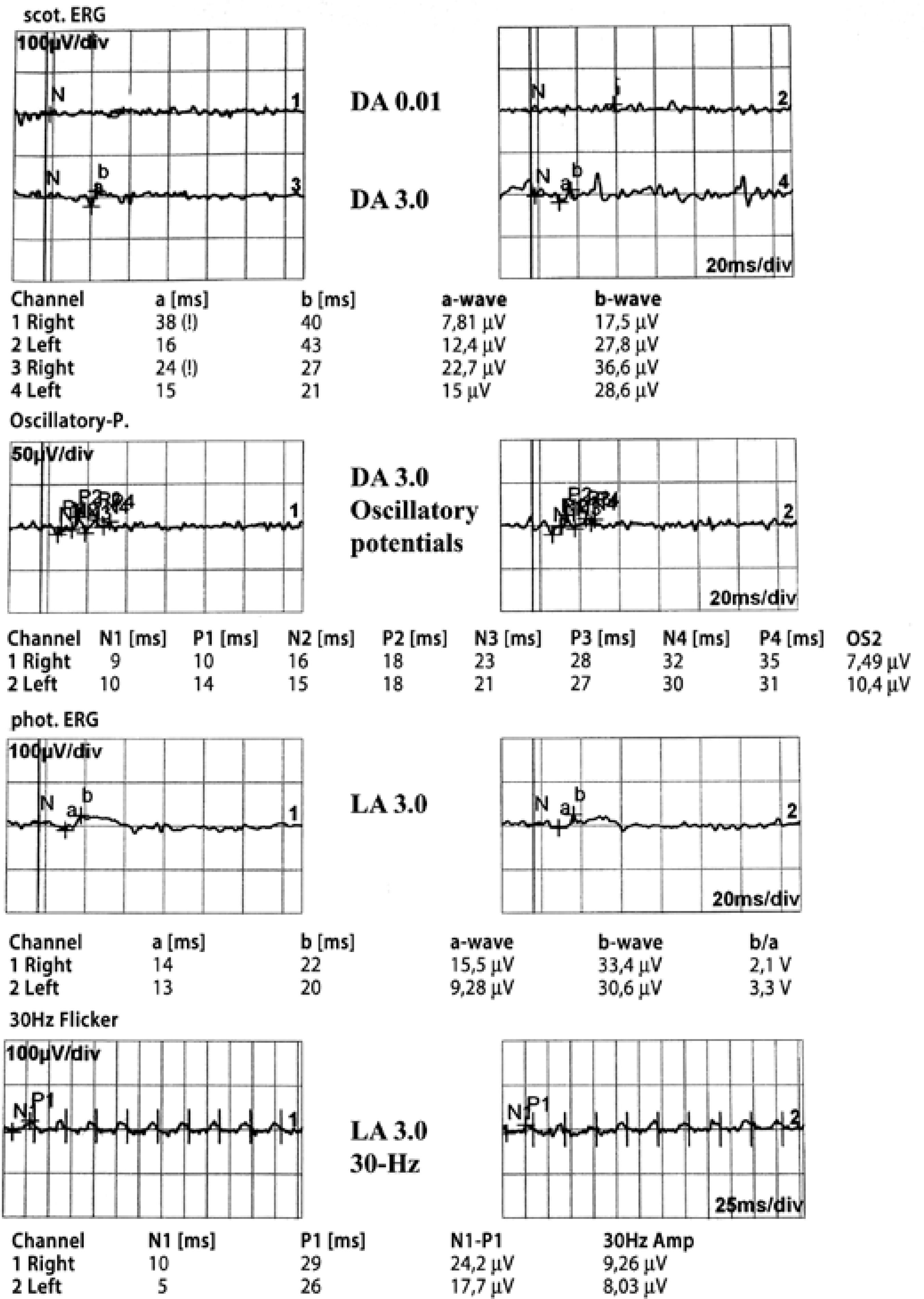

A full field flash electroretinogram analysis was conducted using the standards of the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV). DTL electrodes were used. Dark-adapted 0.01 electroretinography (ERG) was non-recordable in both eyes and dark adapted 3.0 ERG was almost non-recordable. The amplitudes of the light-adapted 3.0 ERG and 30 Hz flicker ERG was severely reduced in both eyes (Figure 2). In the dark adaptation curve, a brief initial cone sensitivity increase was detected. No rod-cone break point was observed and no further rod sensitivity increase was detected (Figure 3). Macular high-resolution SD-OCT did not reveal an epiretinal membrane in the central retina of either eye (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we present a case of FEVR and rod-cone dystrophy. Although the pathogenesis of FEVR is not completely clear, a number of mutations have been defined for specific disease subtypes. Furthermore, the genetic inheritance pattern is varied, and may be autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked, or sporadic. However, the autosomal dominant form is most commonly observed, and mutations in at least four genes have been associated with FEVR. Mutations to the frizzled family receptor 4 (FZD4) gene are responsible for the autosomal dominant form, while mutations to the NDP, LRP5, and TSPAN12 genes are responsible for the X-linked, dominant, and recessive forms, respectively(6-9). The NDP gene is also responsible for the pathogenesis of incontinentia pigmenti, ROP, and Norrie's disease. As our patient's father and brother suffered from the same symptoms, autosomal dominant inheritance can be assumed.

FEVR is characterized by various combinations of macular dragging, temporal radial retinal folds, peripheral avascularity, retinal neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, and subretinal exudation(2). As the disease progresses, complications due to ischemia and fibrovascular proliferation threaten vision. Optic nerve atrophy, cataracts, glaucoma, chronic subfoveal exudation, and strip keratopathy may also contribute to vision loss if present(4).

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a generic term used for a group of hereditary retinal diseases that are characterized by degeneration of photoreceptors and pigment accumulation in the retina. The disease displays genetic heterogeneity, similar to FEVR. Autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked patterns are all possible. Forty-five different gene loci have been reported to be associated with the disease, but in almost half of the cases no specific causative mutation has been found(10). RP is usually seen as an isolated disease in the retina, but in 20-30% of cases it may present systemic associations. As in FEVR, symptoms may differ but peripheral visual field deficiency, nyctalopia, and central vision loss in the late period are certain. Although rod dysfunction is prominent even in the disease's early stages, some cases show simultaneous rod and cone dysfunction or dominant cone degeneration. Cataract, vitreous degeneration, retinal vascular attenuation, intraretinal pigmentations, and a waxy appearance of the optic disk head are other possible clinical signs. In our patient, the symptoms of nyctalopia in association with non-recordable rod responses and reduced cone responses, was sufficient to make a clinical diagnosis of rod-cone dystrophy. The typical symptoms and signs of rod cone dystrophy in a patient with typical fundus findings of FEVR makes this patient an interesting case.

Only a few previous studies have presented the electrophysiologic features of FEVR and, to our knowledge, an association between FEVR and any hereditary fundus dystrophy, including rod-cone dystrophy, has not been previously reported. Feltman et al. examined six patients in a family with FEVR and found that electroretinographic responses were normal(11). In addition, Nicholson et al. examined four cases and all electroretinograms were within normal limits, except for one eye of a single patient(12). In contrast to these findings, Ohkubo et al. reported abnormal ERG findings (a reduction of oscillatory potentials, a and b waves of bright white flash ERG, and scotopic and photopic b waves) in two cases(13). We speculate that these findings were possibly related to the general retinal destruction due to FEVR. However, in our patient, the complaint of nyctalopia beginning from early childhood, and the very subtle fundus findings in association with the ERG findings, dictates that our patient had both FEVR and rod-cone dystrophy simultaneously.

In conclusion, this case report is possibly the first to report the coexistence of FEVR and rod-cone dystrophy. Genetic analyses and detailed clinical descriptions should be provided in further case reports.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin