INTRODUCTION

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) used in ulcerative keratitis may delay healing of epithelial lesions and enhance corneal stroma degradation(1,2). An elevated expression of different metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the cornea locally treated with sodium diclofenac or ketorolac tromethamine has been demonstrated, even without preservatives(2,3).

Nitric oxide (NO) is a simple gaseous molecule found in small quantities in atmospheric air. It is synthesized with the help of nitric oxide synthase (NOS)(4). Three distinct forms of NOS have been recognized: two constitutive isoforms [nNOS (NOS-1) in the nervous system and eNOS (NOS-3) in endothelial cells] and the iNOS inducible isoform (NOS-2)(5), which is expressed in different cells following transcriptional activation by cytokines or endotoxins(6). In ocular tissues, NO is involved in different events(7). In vitro, it has been demonstrated that stimulation of endothelial and bovine keratocyte cells by lipopolysaccharides and cytokines induces iNOS expression, releasing a large amount of NO(8). iNOS expression in corneal lesions induced by ultraviolet radiation has been verified(9). In vivo, high levels of NO can be involved in corneal inflammatory diseases(8). iNOS has been expressed in chemically ulcerated murine corneas, inhibiting neovascularization(10). Peroxynitrite and NO reduce the levels of the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1), increasing the gelatinolytic activity of MMPs in corneal fibroblasts cultivated in vitro(11).

MMP-9 is produced by epithelial cells and neutrophils and has a role in remodeling the corneal stroma after keratectomy(12). MMP-9 is involved in corneal stroma degradation, facilitating the migration and proliferation of neo-vessels in ulcers(12). iNOS expression has been studied in corneal ulcers caused by alkali(10); however, the effect of NSAIDs on its activity is unknown.

Ketorolac tromethamine is used in ocular pain control, despite being toxic to the epithelium(3), and is capable of raising MMPs expression(2). In addition, its activity can be increased by iNOS, as demonstrated in vitro(11).

The present study aimed to evaluate the effect of 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine without preservative on iNOS and MMP-9 expression in rabbit corneas with ulcers chemically induced by sodium hydroxide (NaOH).

METHODS

Male rabbits (average weight, 3.4 kg; age, 120 days) of the White New Zealand breed were selected [Oryctolagus cuniculus (Linnaeus, 1758)]. Animals were evaluated prior to the experiment using biomicroscopy with a slit lamp (XL-1 Slit lamp®; Shin-Nippon, Japan), applanation tonometry (Tono Pen XL®; Medtronic, Jacksonville, U.S.A.), indirect binocular ophthalmoscopy (Indirect Binocular ophthalmoscope FOH®; Eyetec S.A.), and fluorescein dye (Fluorescein 5 strips®-Ophthalmos Ltda., São Paulo/SP, Brazil). Healthy animals were individually housed in a ventilated environment, in appropriate, clean, and sanitized cages with a diet based on commercial food and drinking water ad libitum.

After induction of anesthesia by intramuscular injection of 15 mg/kg of ketamine [(S)-(+)-Ketamine®; Cristália, São Carlos/SP, Brazil] with 0.5 mg/kg midazolam (Dormire®; Cristália, São Carlos/SP, Brazil), periocular trichotomy was performed. A drop of proximetacaine was instilled (Anestalcon®; Alcon, São Paulo/SP, Brazil), and antiseptic treatment of the cornea, conjunctival sac, and conjunctivae were performed with iodine-polyvinylpyrrolidone (Laboriodine; Glicolabor Ind. Farmacêutica Ltda, Ribeirão Preto/SP, Brazil) diluted in saline (Sodium Chloride Solution 0.9%; JP Indústria Farmacêutica, Ribeirão Preto/SP, Brazil; 1:50). General anesthesia was achieved using masks with isoflurane (Forane®; Cristália, São Carlos/SP, Brazil), diluted in 100% oxygen in an open circuit.

After routine preparation of the operation field, a disk of filter paper (Whatman No. 40; F. Maia Ltda, Cotia/SP, Brazil), 6.0 mm in diameter, soaked in a solution of 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was gently maintained over the paracentral region of the cornea for 1 min. Immediately, careful washing of the entire corneal surface with saline solution 0.9% was performed.

Immediately after the lesions have been inflicted, 12 eyes were treated with 30 µL of 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine (Acular®; Allergan, Guarulhos/SP, Brazil), without preservatives (the treated group, TG), and 12 other eyes received, under similar regimen, 0.9% saline solution (control group, CG), both at regular intervals of 6 h, until the collection of corneas.

With lesions lasting for 24 h (M1, first moment), six corneas (n=6) from each group were collected. Remaining corneas (n=6) were collected after re-epithelialization (M2, second moment). Immediately, the preparation of samples for histology and immunohistochemistry was performed.

For monitoring re-epithelialization, clinical observations was performed using fluorescein dye tests and biomicroscopy with slit light and cobalt blue filter (Fluorescein in stripes®; Ophthalmos, São Paulo/SP, Brazil) every 6 h.

Histology

Corneas were processed and analyzed at the Laboratory of Immunohistochemistry at the Department of Veterinary Pathology, College of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences, State University of São Paulo, Jaboticabal, SP, Brazil. The specimens were maintained in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h and then in 70% alcohol for 3 days. Next, samples were embedded in paraffin and cut sagittally in 5-µm sections. Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) was used for staining.

Using 40× light microscopy magnification (Olympus BX51; Olympus Optical Brazil, Ltda., São Paulo/SP, Brazil), the epithelial and conditions of the newly formed stroma were analyzed with regard to cellularity, disposition of collagen fibers, and inflammatory infiltration. Three random fields in the center of the corneas (adjacent to the lesion area) and three fields in the periphery (adjacent to the limbus) were analyzed.

Immunohistochemistry

Five-micrometer-thick sections were mounted on electrically charged slides and processed, employing the streptavidin-biotin complex technique, for labeling of iNOS and MMP-9. Sections were deparaffinized and hydrated in decreasing xylene batteries, followed by alcohol dehydration and rinsing in distilled water. Endogenous protein blocking was performed (Protein Block-DAKO® X0909). Retrieval of antigens was performed under heat and pressure (Pot Pascal-DAKO® S2800) in 10 mM buffered solution of sodium citrate with pH=6.0. Next, polyclonal primary antibody against iNOS (1:600) and MMP-9(1:200) were added. The material was incubated in a humid, dark chamber at a temperature of 23°C for 14 h. As secondary antibody, a polymer bound with peroxidase (ADVANCE-DAKO® K4069 HRP Rabbit/Mouse) was used, followed by incubation in a humid, dark chamber for 1 h. Visualization with diaminobenzidine chromogen (DAB; EnVision + System-HRP-DAKO®) was eventually performed. Counterstaining was performed using Harris’s hematoxylin. For the negative control, only the primary antibody was excluded from the reaction. Slides were washed three times for 5 min using PBS (pH=7.4).

For quantification, average values of three random fields were calculated during evaluation of epithelial immunostaining, using a semiquantitative index(13). For stromal immunostaining, three random fields in the central region (adjacent to the lesion area) and three fields in the peripheral region (adjacent to the limbus) were counted.

Statistical analysis

Data were evaluated for normality employing KolmogorovSmirnov’s test. Variance analysis was used for repeated measurements, and further analyses were conducted using Bonferroni’s and Tukey’s tests. Correlations between immunostaining scores of iNOS and MMP-9 and between iNOS and the amount of inflammatory cells were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation test. A minimum significance level of p<0.05 was used. It was considered that variables showed weak correlation when p<0.05, moderate correlation when p<0.01, and strong correlation when p<0.001. Results were expressed as means and standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

Average epithelialization time was 55 ± 0.84 h (second time) in TG and 44 ± 1.06 h in CG (p=0.001).

Histology

Sections stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin staining exhibited areas denuded of epithelium; this was more extensive in corneas treated with 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine without preservative than those of CG after 24 h. The newly formed epithelium in TG was largely characterized by a single layer. Control corneas showed newly formed epithelium, with alternating areas of single and two or more layers.

At M2, the treated corneas proved to be epithelialized, sometimes exhibiting areas of epithelium in double layers still not adhering in the center of the lesion. In the same period, control corneas revealed a higher stratification.

Regarding stromal conditions, in both groups and at both moments, low cellularity, collagen fiber disorganization, and edema were observed.

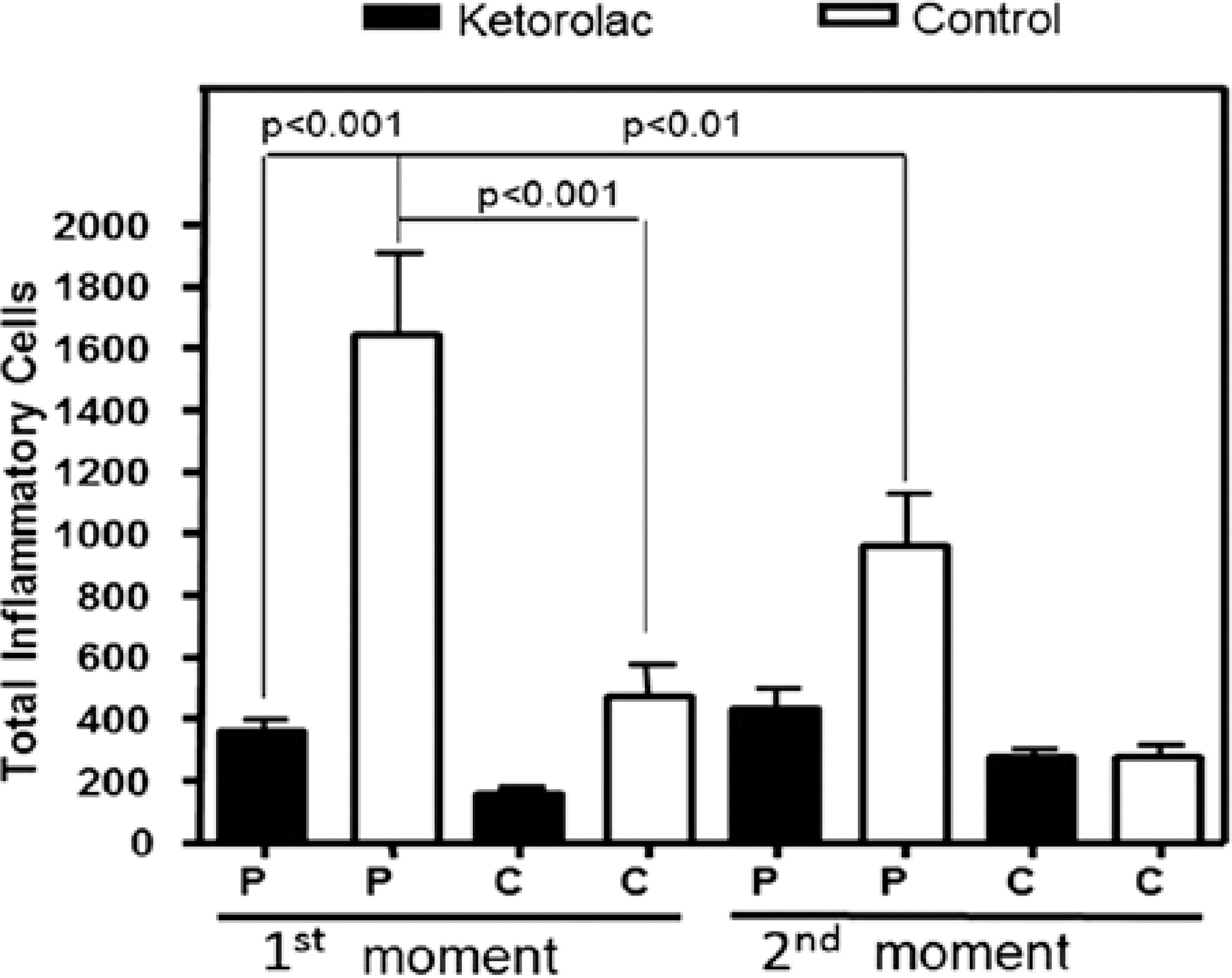

Regarding inflammatory cellularity, control corneas exhibited margination and diapedesis of polymorphonuclear cells, with a predominance of neutrophils and with mononuclear cells being rare. After 55 h, a mild inflammatory exudate was noticed in the treated corneas, with rare polymorphonuclear and inflammatory mononuclear cells compared with controls. The amount of inflammatory cells in the corneal periphery at M1, was significantly lower in the TG (395.5 ± 40.97) compared with the CG (1644 ± 246.6; p<0.001). Values were also smaller in the central region of TG (159.7 ± 25.06) at 24 h compared with the CG (474.8 ± 104.3; p>0.05). Moreover, at M1, the amount of inflammatory cells in the periphery of control corneas (1644 ± 246.6) was significantly higher compared with that in the central area (474.8 ± 104.3 cells; p<0.001; Figure 1). At M2, the amount of inflammatory cells in the periphery was lower in TG (430.5 ± 71.41) compared with CG (960.3 ± 170.3). In the central region, similar results were found in TG (276.3 ± 30.11) and CG (277.8 ± 40.53; Figure 1). The number of cells in the corneal periphery of CG significantly decreased between M1 and M2 (p<0.01; Figure 1).

Figure 1 Mean and standard error* of numbers of inflammatory cells in the periphery (P) and center (C) of male adult rabbit corneas ulcerated with 1 M NaOH and treated locally with 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine without preservative (gray) or with 0.9% saline solution (white) at first moment (M1, 24 hours after chemical burn) and second moment (M2, after reepithelialization). *Bonferroni’s Test.

Immunohistochemistry

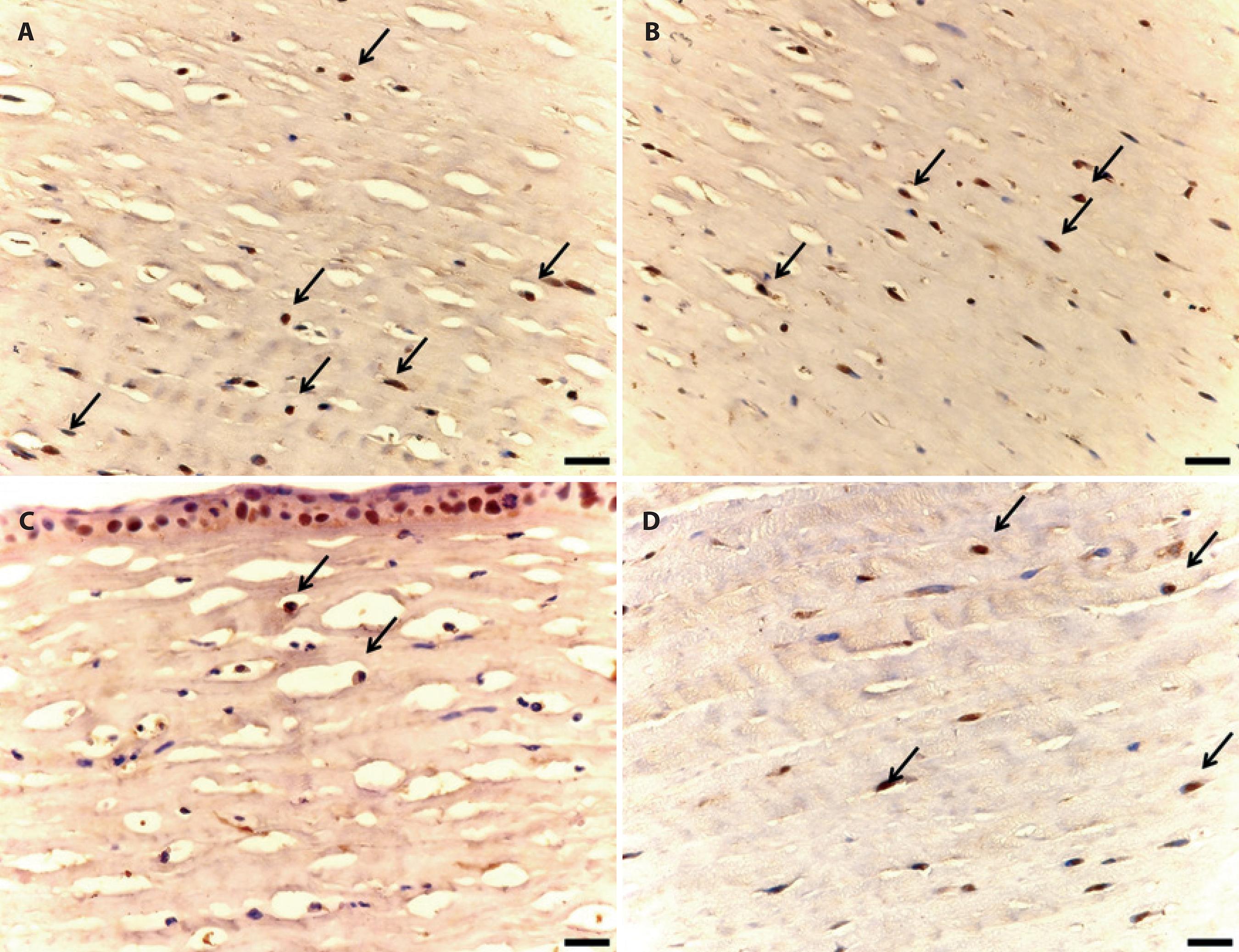

iNOS immunostaining of the epithelium was conspicuously more intense in the margins of the lesions. Regarding the stroma, immunostaining of the cytoplasm and of the nuclei of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells and keratocytes was observed to be more intense in the region adjacent to the lesion (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Photomicrographs of iNOS immunostaining of male adult rabbit corneas ulcerated with 1 M NaOH and locally treated with 0.5% tromethamine ketorolac (A and B) without preservative or (C and D) with 0.9% saline solution. A) Immunostained cells (arrows) in the corneal stroma treated at first moment (M1, 24 hours after chemical burn). B) Immunostained cells (arrows) in the corneal stroma treated at second moment (M2, after reepithelialization). C) Immunostained cells (arrows) in the control corneal stroma treated at M1. D) Immunostained cells (arrows) in the control corneal stroma at M2. Diaminobenzidine. (Scale bar=50 µm).

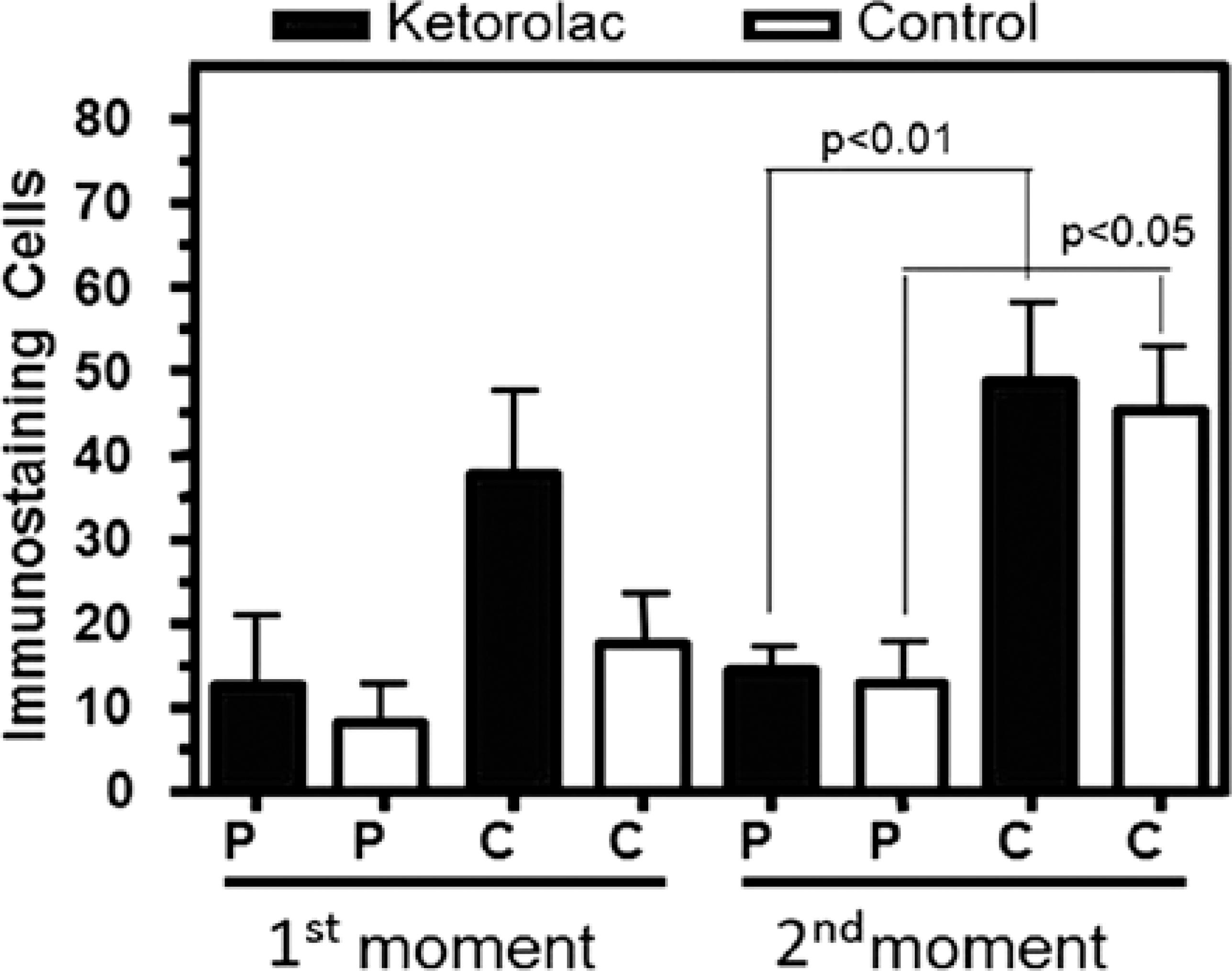

At M1, iNOS expression in the corneal epithelium was similar between the two groups. At M2, a non-significant lower expression was observed in TG (1.5 ± 0.22) compared with CG (2 ± 0.44; p=0.69; Figure 3).

Figure 3 Mean and standard error* of quantitative iNOS immunostaining of stromal cells in the periphery (P) and center (C) of male adults rabbit corneas ulcerated with 1 M NaOH and treated locally with 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine without preservative (gray) or with 0.9% saline solution (white) at first moment (M1, 24 hours after chemical burn) and second moment (M2, after reepithelialization). *Bonferroni’s Test.

When the periphery and the stroma center were analyzed at M1, no difference in iNOS expression in the treated corneas was observed. At M2, a significantly higher expression was found in the central region (48.83 ± 9.93) of treated corneas compared with the peripheral region (14.5 ± 2.88) in the same group (p<0.01). iNOS expression in the central region (45.5 ± 7.43) in control corneas was significantly higher compared with the peripheral region (12.67 ± 5.07) at M2 (p<0.05; Figure 3). At M1, there was no difference between the regions in the two groups.

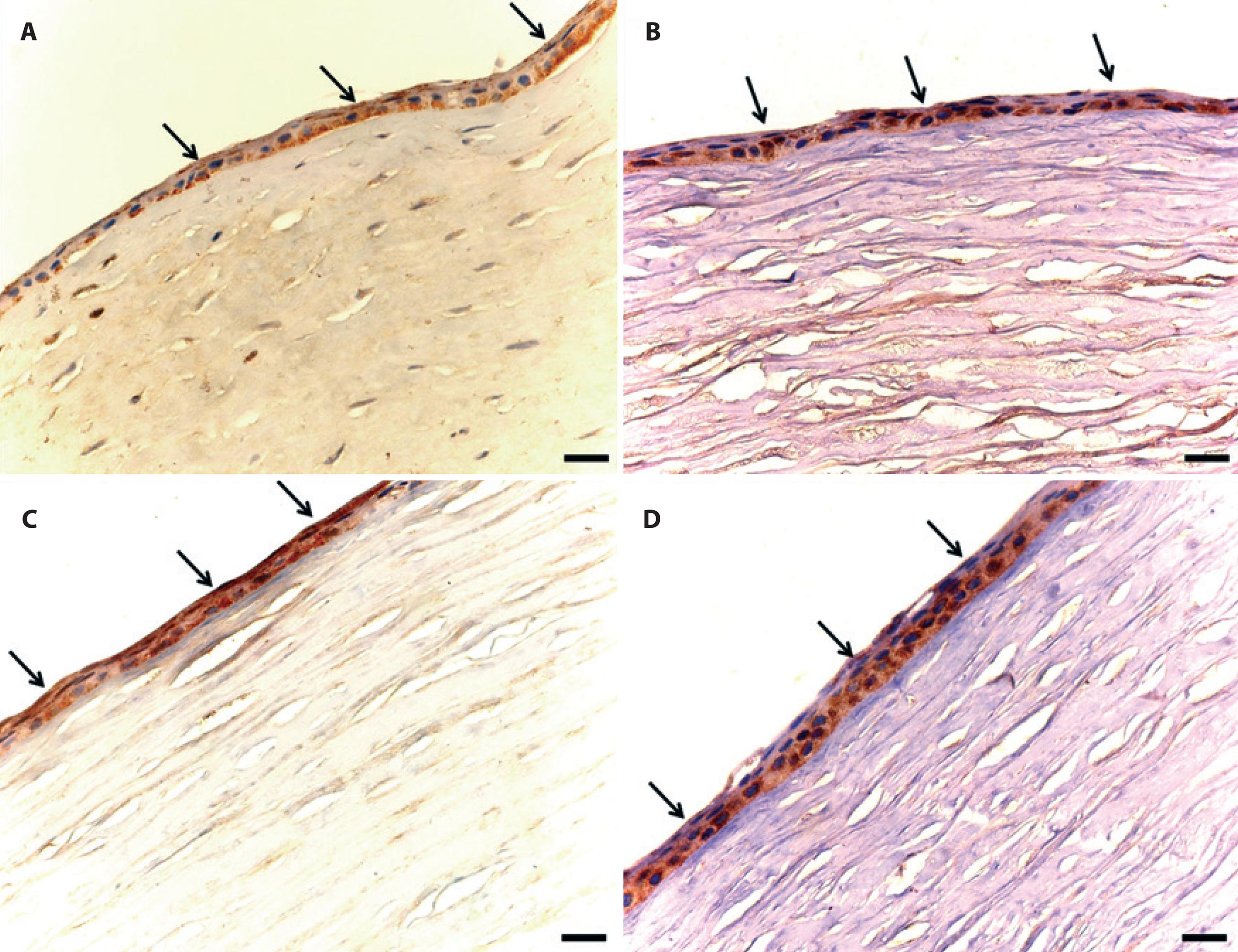

Regarding MMP-9, immunostaining was predominantly evident in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells (Figure 4). MMP-9 expression was observed in smaller quantity in keratocytes and in polymorphonuclear and in mononuclear cells.

Figure 4 Photomicrographs of MMP immunostaining in male adult rabbit corneas ulcerated with 1 M NaOH and locally treated with 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine (A and B) without preservative or (C and D) with 0.9% saline solution. A. Immunostaining of the corneal epithelium (arrows) treated at first moment (M1, 24 hours after chemical burn). B. Immunostaining of the corneal epithelium (arrows) treated at second moment (M2, after reepithelialization). C. Immunostaining (arrows) of the control cornea at M1. D. Immunostaining of the epithelium (arrows) of the control cornea at M2. Diaminobenzidine (Bar=50 µm).

When assessing immunostaining scores in the epithelium of treated corneas at M1, a lower MMP-9 expression was observed (1.16 ± 0.16) compared with CG (1.5 ± 0.34). At M2, MMP-9 expression in the epithelium of treated corneas was lower (1.5 ± 0.3) compared with the expression observed in CG (1.5 ± 0.22); however, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.69).

Regarding average quantity of immunostained cells at M1, MMP-9 expression was lower in the periphery of treated corneas (7 ± 1.98) compared with control corneas (23.5 ± 7.34; p<0.001). In the central region, there were negligible differences between TG (24 ± 9.45) and CG (26.5 ± 8.92). At M2, the mean quantity of immunostained cells in the periphery of treated (9.16 ± 4.24) and control (9 ± 3.97) corneas did not differ. In the central area, there was a higher expression in TG(22.83 ± 13.41) than in CG (15.5 ± 6.52). No significant difference was found when comparing the values (p=0.32).

No correlation was observed between iNOS and MMP-9 in the epithelium of TG (r=0.30 and p=0.34) and in the stroma of treated (r=0.20 and p=0.54) and CG (r=0.41 and p=0.18). Moderate correlation (r=0.70 and p=0.01) was observed between iNOS and MMP-9 expression in the epithelium of CG.

No correlation was observed between iNOS expression and the amount of inflammatory cells in the stroma in TG (r=0.28 and p=0.38) or CG (r=0.56 and p=0.06).

DISCUSSION

Repeated instillation of ketorolac tromethamine influences the development of corneal lesions(14) as also evidenced by the results found in this study. The commercial formulation, i.e., without preservatives, was chosen because it may be toxic to the epithelium(15,16). Control corneas epithelialized faster, and this observation supports the fact that the used drug was toxic and the effect could have resulted from changes in the cytoskeleton of epithelial cells(17). Similarly, desquamation and decrease in microvilli in corneas treated with ketorolac tromethamine without preservatives have been observed(3).

The effect of ketorolac tromethamine and its preservatives on the epithelialization of debrided corneas with 95% ethyl alcohol has been studied in rabbits(14). The authors found that eyes treated with NSAIDs were still ulcerated 60 h after abrasion. In the present study, treated eyes had epithelialized by 55 h following abrasion.

The present investigation showed significantly lower inflammatory exudation in treated eyes. Similar findings were presented after using ketorolac tromethamine with preservatives in chemical ulcers in rabbits(14). Infiltration by polymorphonuclear leukocytes, mainly neutrophils, is necessary for epithelialization. The inflammatory infiltrate influences resident cells by producing cytokines that modulate tissue repair(18).

The number of inflammatory cells in the periphery was higher in control corneas. The amount of cells in the central region did not significantly differ between the groups. In a sterile inflammation model, central infiltrates consist mainly of neutrophils and monocytes(10); this in agreement with the findings of this study.

It has been demonstrated that iNOS is expressed in rat corneas during the inflammatory course following chemical abrasion by alkali(10). The expression reached a maximum between 4 and 7 days following cauterization in the central corneal area. These data were consistent the findings of this study, in which the greatest number of positive iNOS cells occurred in M2 of the evaluation; in the central region, despite a higher number of inflammatory cells in the periphery.

Immunostaining of iNOS were similar to that observed for neutrophils(10). However, few cells showed positive labeling for macro-phages. These observations suggest that neutrophils and monocytes may be the primary source of NO in corneas. Using the same model of chemical abrasion and considering the type of inflammatory infiltrate found in the corneas in this study, the same cells are speculated to be involved in iNOS expression. However, no correlation between iNOS expression and the amount of inflammatory cells was found. Langerhans cells have been found in the central epithelium after thermal cauterization(19) and they may act in NO production.

Immunostaining of iNOS in keratocytes was observed in areas adjacent to the lesions. In vitro, iNOS may be expressed by keratocytes upon stimulation by cytokines(8). The possibility that these cells have contributed to in vitro production of NO could not be excluded. Reactions that occur in different stages of corneal repair, however, are complex compared with those processed in vitro(10).

iNOS expression was higher when compared with controls but the difference was nonsignificant. Contrary to these results, a proangiogenic role of NO in vitro has been reported(20,21). Such differences may be related with the expression of distinct isoforms of NOS dependent on the experimental model employed. The mechanism by which NO inhibits angiogenesis in the corneal cauterization model is not completely understood. However, it is clear that inhibition of angiogenesis by iNOS decreases the amount of inflammatory cells by inducing apoptosis(22). When inhibiting inflammatory exudation, NSAIDs decrease neovascularization, with iNOS playing an important role. Involvement of other NOS isoforms, except iNOS, in vasculature induction has been demonstrated(9). These findings justify the expression of iNOS in TG and the lack of correlation between an event and the amount of inflammatory cells.

Kim et al. studied iNOS immunostaining after laser-assisted lamellar keratoplasty(22). Chen et al. observed iNOS immunostaining in corneal epithelium upon stimulation by ultraviolet radiation(9). In the present study, iNOS expression was similar in both groups, despite the study drug being toxic to the epithelium.

Regarding MMP-9, we observed pronounced immunostaining in the epithelial area adjacent to the lesion. Authors have reported that basal epithelial cells synthesized MMP-9 in corneas that underwent lamellar keratectomy(23); in addition, inflammatory cells and keratocytes were positive by immunostaining for MMP-9.MMP-9 is involved in the early stages of corneal epithelium repair(23,24). In the present study, MMP-9 expression was observed in the epithelium at both M1 and M2. When stromal cells were evaluated, a higher expression in the corneal central region was observed at M1. The highest activity of MMP-9 was observed at M1, which was also observed in cases of keratotomy(23).

Changes in MMPs due to the local use of NSAIDs may delay corneal epithelium repair(25). Collagenases may impair cicatricial healing, breaking the basal membrane interactions of epithelial cells(25). MMP production was found in the intact corneal epithelium after NSAIDs instillation(2). Such findings indicate their involvement in the worsening of corneal ulcers(2,25).

Delayed corneal repair associated with the use of local NSAIDs and expression of MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-2 at significantly high levels, and low levels of MMP-9 in corneas treated with ketorolac tromethamine have been reported(2). In this study, lower expression of MMP-9 was observed in the epithelium of TG compared with CG, but without significant differences. Other authors found no difference in the expression of MMPs; however, differences in the amount of MMP-9 and MMP-2 were determined by zymography(26).

In inflammatory processes, it has been demonstrated that NO and peroxynitrite can alter levels of MMPs and tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs)(27). However, no correlation between MMP-9 expression and iNOS was found in this study. Data are available on the involvement of oxidative stress in inflammatory processes, in which macrophages, polymorphonuclear cells, and other inflammatory cells are involved in the activation of lytic enzymes(11). High concentrations of peroxynitrite in vitro reduced TIMP-1 and hence the inhibition of MMP-9(28). Similar results were found by Brown et al.(11) in 2004, showing a cellular response to oxidative stress induced by peroxynitrite, suggesting a relation between elements of oxidative stress with activity of degradative enzymes. Other MMPs may be activated and involved in the reactions, as would be with regard to the higher activity of TIMPs.

Based on the obtained results, 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine without preservative may induce less inflammatory exudation and delay corneal epithelialization, eliciting non-significant changes in the expression of iNOS and MMP-9.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Scielo

Scielo

Pocket

Pocket

Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin